Governance Amid Technological Disruption: A Vision for an Agile Public Service

ETHOS Issue 18 Jan 2018

Will robots take our jobs? Can Artificial Intelligence (AI) be applied ethically and safely? What will happen when self-driving cars and flying drones are in widespread use? How should government regulate emerging technology without stifling innovation? As far as evidence goes, a reasonable answer to all of the above might be: we don’t really know.1

We know the pace of technological advancement has accelerated significantly. But the net impact from these developments will result not from technology alone, but from its interaction with a broader set of demographic, economic, social and environmental factors. Around the world, governments are still feeling their way around these uncertainties. How should we begin to think about governance amid technological disruption?

Clockspeeds Out of Sync

In management theory, each industry is shaped by its own clockspeed (akin to an evolutionary life cycle), defined as the rate at which it introduces new products, processes, and organisational structures.2 We adapt this definition to the public policy context, and introduce three clockspeed concepts for understanding governance in a Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous (VUCA) environment: technology, policy, and risk.

Technology clockspeed is the rate at which technological innovation reaches mass adoption in a specific domain.3 It has been accelerating since the First Industrial Revolution began 200 years ago, and looks set to continue as we enter the Fourth Industrial Revolution.4

Meanwhile, policy clockspeed—the duration of a policy cycle and policy response time—has not kept pace in some domains.5 In some cases, this has resulted in government action lagging so far behind as to render it irrelevant: the US Federal Aviation Authority took eight months to grant Amazon an “experimental airworthiness certificate” to test a model of flying drone, by which time the model was obsolete. In other cases, slow regulatory responses towards emerging technology have triggered market-led efforts to fill the void—the European Regulatory Initiative led by blockchain investment platform Neufund was a response to the silence of regulatory authorities towards cryptocurrencies, blockchain technology, and Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs). The Partnership on Artificial Intelligence, which aims to set social and ethical best practices for AI research and applications, is led by industry players like Google, Facebook, Amazon, IBM, and Microsoft.6 Policymakers are noticeably absent from the conversation.

When policy clockspeed is out of sync with an accelerating technology clockspeed, we are in a high risk clockspeed environment.7 In such an environment, the ability of decision-makers to process, understand, and react to the changing environment is diminished, because actionable information, expertise, and timely levers are not easily available. These varying clockspeeds create a conundrum for policymakers: How do we regulate or govern technology we do not understand or have sufficient control over? How can the public sector keep pace?8

Accelerating Policy Clockspeed: Three Ideas

For Singapore’s public sector, managing emergent technology risk has largely involved designing regulatory sandboxes, or adopting a “wait-and-see” position, in order to avoid stifling innovation through premature regulation. The Monetary Authority of Singapore’s (MAS) FinTech regulatory sandbox, for example, enables financial institutions and financial technology (Fintech) startups to experiment with new ideas for a limited duration of time, without having to worry about whether their technology meets existing regulatory requirements.9 More recently, MAS has also adopted a “wait-and-see” approach to regulating cryptocurrency.10

There is certainly a place for such strategies: they buy time for more relevant information to be incorporated into the policymaking process. However, they do not fundamentally hasten the policy cycle clockspeed. As the gap between technology and policy clockspeeds continues to widen, policymakers and regulators may eventually be forced to tradeoff innovation for risk management.

Policy clockspeed should also be proactively accelerated at the same time, particularly in high risk clockspeed domains. This would involve building and harnessing expertise, learning by doing, and developing the agility to operate at the frontier of emerging technologies. Ultimately, for the government to govern technology effectively, it needs to be in the very sandbox it is creating: to become an expert adopter of technology, rather than just an informed regulator waiting on the sidelines.

Three new ideas may help accelerate policy clockspeed:

1. RALLY “POLICY COMMANDOS”

When Singapore’s MRT Circle Line was hit by a spate of mysterious disruptions in late 2016, a team of three GovTech data scientists stepped up to support investigations. Using data from train operator SMRT and the Land Transport Authority (LTA), they pinpointed a rogue train, PV46, as the cause of breakdowns in all but three hours, and, together with the inter-agency investigation team, caught the rogue train by sundown. No machine learning, no AI, no fancy technical methods were involved. In fact, what shone a new light on the mystery was a simple scatterplot (inspired by the Marey Chart). [For more on this story, see “Data Science in Public Policy—The New Revolution”, in ETHOS Issue 17.]

What made the difference was the applied experience of the data scientists, who had honed their analytical skills and instincts through collaboration with agencies on data science projects across varied policy domains. They knew where to begin their sleuthing, which methods to try, and most importantly, which features to visualise on the scatterplot. Their efforts helped achieve a critical objective (identify the source of the problem), which proved decisive in turning the tide. But it took the entire corps to win through: in this case, DSTA engineers narrowed down the hardware issues with PV46, while transport planners coordinated train schedules, and information officers engaged the public.

Quality decision-making under a fast clockspeed environment requires domain expertise, but also sometimes—as in the case of the rogue train mystery—non-domain expertise, which can help decision-makers think out of the box. A government adept at responding to fast clockspeed risks would develop and retain a core of diverse technical talent, and design institutional structures that allow both domain and non-domain experts (“policy commandos”) to work collaboratively on problem solving. These interdisciplinary taskforces would be empowered by senior management, and comprise functional experts (a mix of policy, operations, technology, and communications specialists) across the Public Service.11

2. LEARN BY DOING

Governments around the world—including Singapore—are in the earliest stages of deploying big data, machine learning, and AI to regulate behaviour and enforce laws. These developments will have profound implications for the relationship between private citizens and the state.

However, the governance of AI is unlikely to be straightforward. Developing algorithms in a sandbox environment is different from operational deployment, where more complex policy and operational issues arise. For example, who bears liability if the AI makes a wrong recommendation? How will an AI recommendation feed into the decision-making process, and when do humans override the algorithm? How important is it to understand why the AI made its recommendation? Who will maintain the algorithm? How much should the public know, and what should we communicate to them about how the algorithm works? How will government manage instances when AI gets things wrong, in order to make good any harm done or trust compromised?

As with all complex issues, the answers to these questions are unlikely to be knowable ex-ante, and the full implications of operational deployment will only emerge after the algorithm is integrated into actual decision-making processes, with real users. The more we experiment, the more real-world feedback there will be to learn from, and the more responsive our policy responses can be. We must learn by doing.

3. THINK AGILE

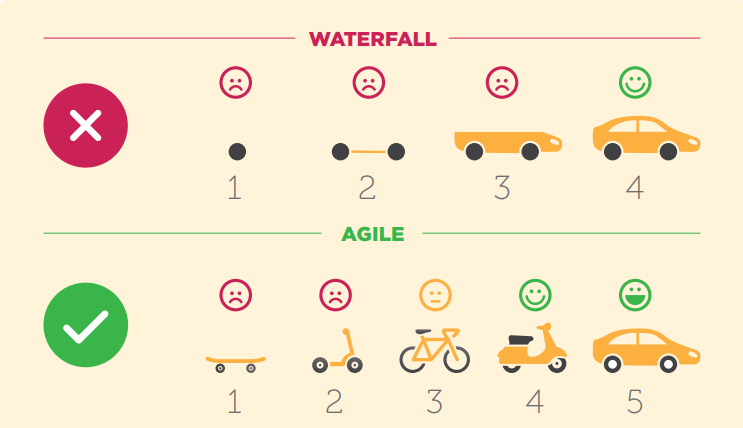

The “waterfall” approach to policymaking is familiar to policymakers: studies are commissioned by committees, their findings deliberated, then stakeholders are consulted, before the policy is finalised and implemented. In an “agile” approach, the policymaker seeks to get a first-cut approximately right, and to iterate with users and stakeholders based on real-world testing and dynamic feedback (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. "Waterfall" versus "Agile" Approach to Product Development12

Being agile is not a formulaic process, but a mindset that rests on several principles:

- Policies are in permanent beta. Policies are not thought of as tending towards any stable equilibrium, but are tweaked according to real-world feedback. Policymakers acknowledge that they do not have all the answers, but are willing to make decisions based on the best available information, and prepared to adjust along the way.

- Iterate based on timely data. Timely information is needed to evaluate impact and inform the next policy iteration. Administrative data should therefore be shared seamlessly and securely—in days, rather than months. Organisational structures should facilitate timely feedback loops so that policy ideas can be continuously tested and evolved based on the evidence.

- Proactively communicate. Transparency is necessary for public accountability, but also for public buy-in to a culture of policy “beta-testing”. For example, if government were to deploy an AI algorithm to enhance delivery of public services, it should state the model and relevant parameters used, the governance framework, and how the algorithm’s performance will be assessed. Communications should also be more tightly integrated into the policy process, to support the evolving policy.

These agile principles represent significant mindset shifts for the public sector, because they mean publicly acknowledging that government does not have all the answers, and accepting a higher level of transparency and public scrutiny. Yet, increasingly, these will become tradeoffs that government has to make in order to remain relevant in a high-risk clockspeed world.13

How can we achieve the vision of an agile Public Service adept at operating under accelerating clockspeeds?

The traditional approach to policymaking—of planners systematically and meticulously thinking through and designing “masterplans” to address challenges of the day, and leaving it to the operational agencies to implement their plans—has generally served Singapore well. There is still a place for such an approach, as citizens will expect rigour, stability, and certainty in some policy domains, such as school placement or housing. However, masterplanning will become increasingly difficult in a rapidly evolving operational environment.

There is room for rethinking how we conceive of “policymaking”, of “policymakers”, and how we build and leverage on expertise across the service. Not all problems in the public sector are solved through policymaking—a parking app, for example, is not a policy per se, but an innovation in service delivery. Accelerating technological clockspeed creates time pressure for policymakers and regulators, but also opportunities to solve problems through new means—to not just regulate, but also innovate; not just create a sandbox, but be in the sandbox. The latter demands a rethink of how we embed functionally diverse roles and expertise within the same team (e.g., policy and operations officers, data scientists, communication specialists working in an integrated policy team) to deliver actual policy solutions that can be rapidly operationalised.

In an age of accelerating technology clockspeeds, effective problem solving cannot be achieved primarily through planning and debate. Problem solving will have to be a process of learning-by-doing, building and leveraging expertise, and delivering through red-teams across agencies, rather than waterfall planning within the silos of agencies. Solutions will be found not in “policy”, “operational”, or “engineering” worlds, but in bringing these together and taking collective ownership over successes and failures. Public officers will be “makers”—creative, innovative, and entrepreneurial—in the truest and most fundamental sense of the word.

Will this new mode of government succeed in navigating Singapore through the Fourth Industrial Revolution? We think building a truly agile Public Service would give us a better chance. Let’s think big, start small, and act fast.

Financial Governance: Playing Catch Up

The financial sector has been especially vulnerable to high risk clockspeed. As more banks use technology to conduct shadow banking activities, regulators are forced to play catch-up. Despite their best efforts, regulators are always several steps behind. Regulations to counter financial fragility have been quickly circumvented by bankers before coming into effect, as demonstrated by each iteration of the Basel Capital Accord. Basel I & II were implemented in the 1990s to counter financial fragility, but was quickly undermined by creative bankers. Regulators recently introduced Basel III to force banks to hold more capital, but these have been circumvented before coming into effect. The failure of central bank regulators to keep up with the digitalisation of financial and banking sectors has proved to be costly, contributing to financial crises in the past three decades.

Note

- Jonathan McMillan, “Banking in the Digital Age: The Failure of Financial Regulation”, The Guardian, January 20, 2016, accessed October 29, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/sustainable-business/2015/jan/20/finance-in-digital-age-while-regulation-stuck-in-industrial.

A small inter-agency, multi-disciplinary team can iterate and deliver on an impactful solution in months, rather than years, by adopting an agile approach.

Case Study: How Parking.SG Evolved from an Idea to National Product in Eight Months

A small inter-agency, multi-disciplinary team can iterate and deliver on an impactful solution in months, rather than years, by adopting an agile approach. Case in point: the Parking.SG mobile app, which grew from idea to national product in just eight months.

PERMANENT BETA

Parking.SG is more than just an app with a well-designed user-interface. Making the concept work involved many interlinked issues, including product engineering, payment infrastructure and enforcement. The team chose not to worry about having the ‘perfect’ app: instead, they had a rough idea for its initial design and architecture, and focused on getting a minimal viable product out to market every four to six weeks. The first prototype app was ‘broken’ in many ways, but worked well enough to validate core concepts for the next iteration. Such agility was only possible because the team had the technical expertise to develop the app in-house, and therefore had full control over product development. This meant the team could actively push back on feature requests from even senior management, if they thought the suggestions bad for the product.

ITERATE BASED ON TIMELY DATA

With each working prototype, the team walked with parking enforcement officers on the ground to observe how they carried out enforcement checks and verified the validity of parking coupons. They also interviewed Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and Housing & Development Board (HDB) operations officers and motorists to understand their needs. These insights and data points were incorporated into the next app version, in a continuous cycle of experimentation, feedback, and rapid iteration. Once the basics were firmly established, the team launched a trial with a small group of public officers within four months to gather real-world feedback. Within eight months, the app was deployed nationwide.1

PROACTIVELY COMMUNICATE

At every stage of development, the team was proactively in touch with stakeholders. The message from the outset was this: the team had released a working app, users can expect bugs and should actively provide feedback for improving subsequent app releases. This helped manage the public’s expectations: ensuring that citizens did not expect the app to be perfect, but instead appreciated the effort to get a useful product quickly to market.

Note

- A team of three GovTech specialists (a product manager, a software engineer, and a UX designer) worked closely with a small team of policy officers and ground enforcement officers from the Ministry of National Development, URA and HDB. The team deployed a minimal viable product for beta testing among public sector users in just four months—the typical time it takes to call for a government tender.

Towards an Agile Public Service—Public Service 2021: A Vision

The year is 2021. The global economy shows signs of slowing, while countries that have harnessed technologies in the Fourth Industrial Revolution are powering ahead. Google has completed its Project Baseline and identified the genomic sequences that increase risk of diabetes. Deep learning algorithms have advanced and are now explainable; San Francisco announces its first AI-enabled hospital.

In response to these trends and events, the Public Service has gone digital to the core and embraced new ways of working across government. Policy by inter-agency, action-oriented red-teams has become the norm. Red-teams are scheme- and paygrade-agnostic, and team composition is drawn from across government and determined by functional expertise.

The project team lead for one of the red-teams is a “generalist” who started out as a data scientist at GovTech for three years, before taking on policy and operational roles at the Ministry of Health (MOH) and Workforce Singapore (WSG). Team members include AI specialists from GovTech who began their careers at Silicon Valley start-ups, a behavioural scientist from the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) with design thinking experience, policy officers from the Ministry of Education (MOE) and Ministry of Manpower (MOM), an information officer from the Ministry of Communications and Information (MCI), and a legal officer from the Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) with experience working on AI and data privacy issues. They are advised by a Taskforce that includes representatives from labour unions, technology companies, and institutes of higher learning. The team has been tasked to deliver actual solutions that can be operationalised, not a slide deck or white paper.

The team is a diverse lot, but they will be working together over the next three to five years to deliver on several pilot projects, some of which will be scaled up through policy interventions. Government is actively encouraging public officers to devote lengthier stints to each posting, and to strongly consider hands-on, technical roles. The distinction between “policy” and “operational” roles has all but disappeared. It is clear that policymaking is not just about analysis, but about making things happen.

The views expressed in this article are the contributors’ own and do not reflect the position of the Government of Singapore.

NOTES

- The authors would like to thank the following individuals for reading earlier drafts and providing valuable feedback: Aaron Maniam, Jason Bay, Beh Kian Teik, Hannah Chia, Joanne Chiew, Chng Kaifong, Dong Yangzi, Gaurav Keerthi, Melissa Khoo, Jasmine Koh, Kwok Jia Chuan, Peter Ho, Li Hongyi, Gabriel Lim, Mark Lim, Liu Feng-Yuan, Robert Morris, Ng Chee Khern, Vernie Oliveiro, Jacqueline Poh, Jeffrey Siow, Tan Gee Keow, Tan Kok Yam, Tan Li San, Wu Wei Neng, Karen Tay, and Leo Yip.

- Charles Fine, Clockspeed: Winning Industry Control in the Age of Temporary Advantage (Reading, MA: Perseus Books, 1998).

- The definition of technology clockspeed will depend on whether our aim is policy response or policy innovation. In domains where we seek policy innovation, then the relevant milestone would be when technology reaches early adoption.

- Alison Berman and Jason Dorrier, “Technology Feels Like It’s Accelerating—Because It Actually Is”, Singularity Hub, March 22, 2016, accessed October 19, 2017, https://singularityhub.com/2016/03/22/technology-feels-like-its-accelerating-because-it-actually-is/

- Policy clockspeed varies across domains, depending on the nature of the policy issue, issue salience, availability of data to evaluate policy effectiveness, and time lag for the policy’s impact to be felt. For example, the Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore (IRAS) amends the income tax structure every five to 10 years; the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) reviews the Workfare Income Supplement criteria every three years; the Ministry of Social and Family Development (MSF) reviews the composition of the ComCare basket annually; MAS reviews monetary policy every six months.

- The “Partnership on AI” was formed by Google, Facebook, Amazon, IBM and Microsoft to set societal and ethical best practice for artificial intelligence research. See Partnership on AI (website), accessed October 29, 2017,https://www.partnershiponai.org/.

- Technology, policy, and risk clockspeeds are highly context-specific. Policymakers should evaluate whether there are high-risk clockspeed domain areas in their own specific contexts, for which policymaking and regulation should be rethought.

- Our article focuses on the public sector and how it can transform itself to be more adept at operating in a high risk clockspeed environment. However, for Singapore as a country to move ahead, society-at-large also needs to adapt. There will be those who fall behind, and government will need to address the issue of technology adoption, inclusion, and the attendant inequalities that might arise. The e-payments space is one example—the technology is available, but not all segments of society are prepared to adopt it; getting them on board requires active change management and applying a citizen-centred lens to the issue.

- Monetary Authority of Singapore, “FinTech Regulatory Sandbox”, accessed October 29, 2017, http://www.mas.gov.sg/Singapore-Financial-Centre/Smart-Financial-Centre/FinTech-Regulatory-Sandbox.aspx.

- Jacquelyn Cheok, “Singapore Not Rushing to Regulate Cryptocurrencies: MAS”, The Business Times, October 26, 2017, accessed October 29, 2017, http://www.businesstimes.com.sg/technology/singapore-not-rushing-to-regulate-cryptocurrencies-mas.

- SMRT and LTA tapped on data scientists from GovTech and engineers from DSTA to help solve the Circle Line mystery—demonstrating that current decision-making processes were effective. To accelerate policy clockspeed, what worked well should be institutionalised and scaled across all of government, to minimise the role of luck or having the right mix of aptitudes involved.

- Adapted from Henrik Kniberg, “Making Sense of MVP (Minimum Viable Product)—and Why I Prefer Earliest Testable/Usable/Lovable, January 25, 2016, accessed November 25, 2017, http://blog.crisp.se/2016/01/25/henrikkniberg/making-sense-of-mvp.

- The agile approach must be applied in tandem with human-centric design, with an empathetic eye on the citizens’ experience.