Survey of Fairness Perceptions in Singapore Public Policy

ETHOS Issue 15, June 2016

Introduction

Fairness is an important facet in policy discussions, because it influences how much support the government gets from the public when rolling out policies. However, there has been little research in Singapore that systematically explores fairness perceptions in public policy. In addition, perceptions of fairness change with time. For example, there are indications of a growing preference in Singapore for universal access to social transfers and support. Changing demographics may have also tilted fairness perceptions towards universal provisions that cater to an ageing population and a middle class that increasingly feels that the deck is stacked against them.

Do Singaporeans have a dominant view of what is fair or unfair in public policy? Are public perceptions of fairness consistent or do they vary across different policy domains? Are these perceptions systemic and what are their implicit rules? We conducted a survey to address these questions.

"It’s my point that every policy that comes out has to be reasoned and reasonable. It’s reasoned in the sense that every policy has its rational grounds based on data, knowledge, for you to come to the best choice of what action to take. But every policy must also be reasonable in the minds of the people who are affected. Reasonableness is an emotional assessment and not a rational assessment. The reasonableness part of it is when the people are going to look at it and say ‘Does that seem fair, does that seem reasonable?’ The policy needs to pass this test."

— Mr Lim Siong Guan, former Singapore Head of Civil Service1

Objectives of the Survey

International surveys, such as the 2009 Bamfield and Horton’s study,2 have highlighted the importance of “progressive universalism” — a system in which everyone receives some benefits, but those in middle and higher income groups receive less than those in the low-income group. Their findings suggest that people would be more willing to contribute to benefits with wider coverage. Bamfield and Horton further highlight that a common complaint was that the system was not generous enough towards the middle or “sandwiched class”. In other words, participants preferred to be treated differently from those at the top for taxes, but not too differently from those at the bottom for benefits.

Even though progressive universalism may be less efficient than a more targeted approach, it might receive higher public support and hence affect the willingness ofthe middle class to pay their share. For example, the British Social Attitudes Survey in 2012 found that 70% of participants opposed the idea of reducing taxes in return for making free health services on the National Health Service (NHS) only available to people with low earnings.3

However, it is worth noting that fairness perceptions may not be consistent across different public policy domains. Sectors such as education and healthcare for instance, may be subjected to different fairness criteria: education is considered fundamental to ensuring equality in opportunity, while medical care is regarded as a good with “special moral importance”.4 Bamfield and Horton’s survey also points out that while people were usually against targeted interventions, many participants were prepared, when presented with evidence of barriers to opportunity, to support public interventions that specifically helped the disadvantaged, even at some cost to the rest of the population.

With these insights in mind, the Civil Service College, Singapore designed and commissioned a “Fairness Perceptions in Singapore Public Policy” survey, with a focus on the distributive fairness of how rights and government resources are allocated. In particular, there was interest to find out how Singaporeans view the targeted, universal, means-tested and universal approaches to allocating rights and public resources.5 It also examined if these fairness perceptions are consistent across different segments of the population and if they continue to be supported even at some cost to individuals (via higher taxes or prices). The survey, conducted in March and April 2014, was administered to a random sample of 1,002 Singaporeans aged 20 and above that closely resembled the demographic profile of Singapore Residents (i.e., age, gender, race, housing type and working status).6

Key Findings

The survey revealed several key insights on Singaporeans’ perceptions of fairness regarding the allocation of government resources.

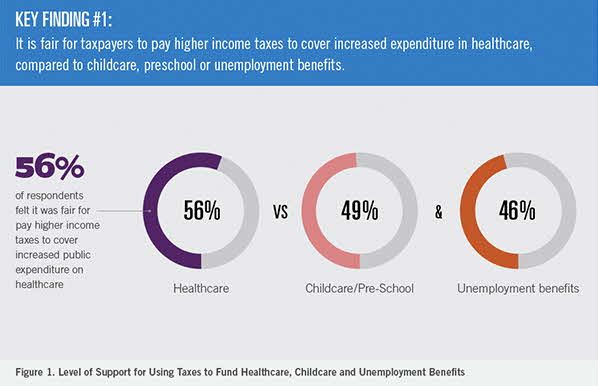

A majority of respondents (56%) felt it was fair for pay higher income taxes to cover increased public expenditure on healthcare. In contrast, for unemployment benefits and childcare/kindergarten, only half or less of the respondents thought it was fair to do so. This could be partly due to the profile of the respondents, as about a third of them (32%) were either single or married with no children, and only 3% were unemployed.

Policies with a wide reach should take on the universal, means-tested approach as this approach would likely to be perceived as fair by the majority of the public.

There was clearly a preference for the universal, means-tested approach to taxes and allocating public resources across most domains. This meant that respondents preferred if everyone received some of the transfers or paid taxes, but the amount of transfer or tax should be differentiated according to income levels.

The universal, means-tested approach was clearly the most preferred for questions related to healthcare, general government top-ups, housing policies and transfers for vulnerable groups, followed by the universal and the targeted approaches (see Figure 2).

This finding could imply that policies with a wide reach should take on the universal, means-tested approach when allocating transfers and tax burdens. This approach would likely to be perceived as fair by the majority of the public and would thus garner more support.

One example would be healthcare services (see Figure 3). The strong preference for a universal, means-tested approach to distributing government healthcare-related transfers was seen in Medisave and Central Provident Fund (CPF) top-ups, where 86% of respondents felt that this approach was fair. In terms of direct public hospital bill subsidies, 80% felt that the approach was fair. This dominant support for the means-test approach was seen even across different income groups, educational levels or gender.

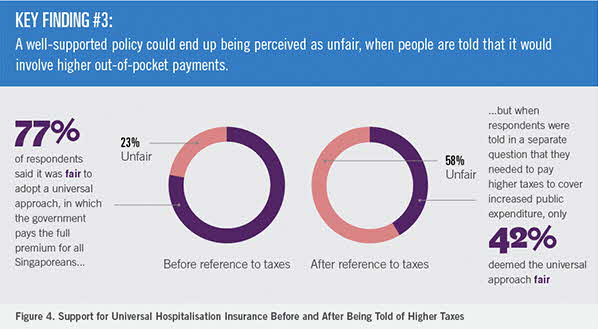

Hospitalisation insurance was one of the exceptions to the preference for a universal, means-tested approach. Instead, there was a strong preference for a universal approach, in which the government pays the full premium for all Singaporeans (77% said it was fair). This support was consistent across all income levels. A possible reason could be due to hospitalisation insurance being viewed as an ‘entitlement’ that the government should provide equally for all citizens.

A larger proportion of those with higher education levels and household incomes seemed to feel that it was fair, even when told of the need for higher taxes or costs to individuals, to support higher public expenditure.

However, when respondents were told in a separate question that they needed to pay higher taxes to cover increased public expenditure, the universal approach was deemed fair by only 42% (see Figure 4). In other words, citizens had strong initial impulses towards the collectivisation of medical insurance, but this was reduced when they realised taxes would rise to support this policy.

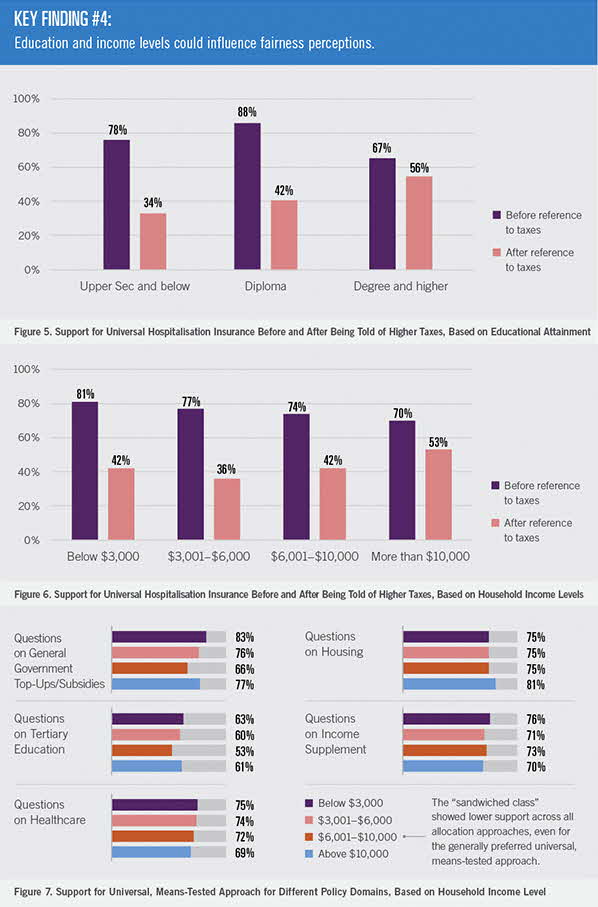

When analysing reactions to increased taxes in return for universal hospitalisation insurance, there were interesting variations based on income levels and educational attainment.

The first observation was that a larger proportion of those with higher education levels and household incomes seemed to feel that it was fair, even when told of the need for higher taxes or costs to individuals, to support higher public expenditure.

In the case of hospitalisation insurance, universal provision was seen as the fairest by all respondents. But degree holders and those with monthly household incomes of $10,000 or more saw the smallest drop (by 11% and 17% respectively) in the ‘fair’ response when they were told of higher taxes needed. The largest drop in support was among diploma holders and those from household incomes between $3,001 and $6,000 per month. Their support dropped by more than 40% once an increase in taxes was factored in (See Figures 5 and 6 for more details).

Similar patterns were observed for questions pertaining to transfers for low-wage workers. More respondents felt it was fair to provide low-wage workers with some benefits. However, at least half of them felt that the policy was unfair when told of the need to pay higher taxes or food prices to fund the support. Again, the fairness ratings among those with higher education levels and household incomes fell the least when told of the financial implications.

A persistently large proportion of the "sandwiched class" consistently viewed the targeted approach as more unfair compared to the other income groups — they are left out from most government transfer schemes while having to pay higher taxes.

The second observation was that the “sandwiched class” showed lower support across all allocation approaches, especially for targeted schemes. The group with $6,001–$10,000 monthly household income expressed lower fairness levels when compared to all other income groups, even for the generally preferred universal, means- tested approach (see Figure 7). This observation was also seen across most policy domains.

In addition, a persistently large proportion of this income group consistently viewed the targeted approach as more unfair compared to the other income groups (both lower and higher incomes). This could possibly be due to the fact that this group viewed themselves as the “sandwiched class”, who are left out from most government transfer schemes while having to pay higher taxes. Hence, they reacted more strongly against the targeted approach that would help only the low-income groups.

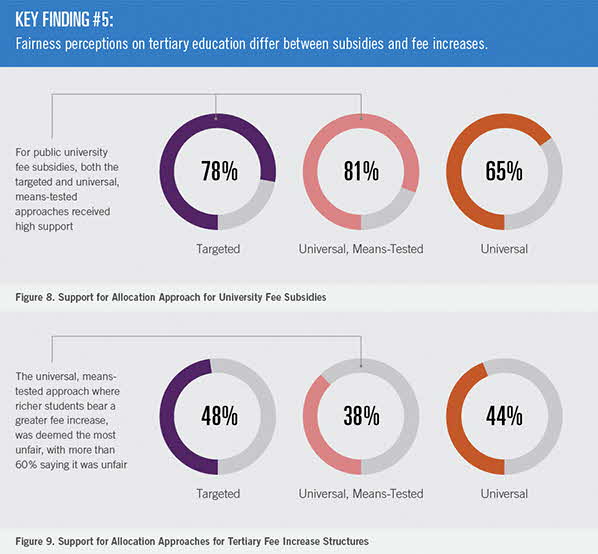

Interestingly, fairness perceptions towards tertiary education subsidies and fee increases were divergent. For public university fee subsidies, both the targeted and universal, means-tested approaches received high support (78% and 81% respectively). On the other hand, only 65% of respondents felt that the universal approach was fair (see Figure 8). Hence, it appeared that respondents felt a strong need to provide relatively more subsidies to students from lower-income households.

When it came to tertiary fee increases, at least half of the respondents already felt that it was unfair to pass the fee increase in any form to the students. Among possible fee increase structures, the universal, means-tested approach, where richer students bear a greater fee increase, was deemed the most unfair (more than 60% said unfair; see Figure 9). While this approach to fee increase would appear similar to the universal, means-tested approach to subsidies, where lower-income groups are favoured, framing it in the context of fee increases yielded a drastically different fairness response.

When it came to tertiary fee increases, respondents from each income group felt that any approach that would place them at a disadvantage compared to others was unfair.

Furthermore, there were differences in fairness preferences by income levels when it came to fee increases. Those from low-income households (below $3,000 per month) felt that it was most unfair when there was no differentiation in fee increase between them and the richer students. On the other hand, those from high-income households ($10,000 and above per month) felt it was most unfair when the fee increase took on a targeted approach and was borne solely by richer students. The most surprising result came from respondents from the middle-income groups, who felt that the means-tested approach was the most unfair while being indifferent to the other two approaches.

There was thus no general consensus when it came to tertiary fee increases. The results suggest that respondents from each income group felt that any approach that would place them at a disadvantage compared to others was unfair. This suggests that unlike other policy domains, tertiary education was not seen in a similar way across different income groups, possibly invoking a notion of opportunity and private benefit.

Conclusion

This survey on “Fairness Perceptions in Singapore Public Policy” offers evidence on how Singaporeans view the way resources and rights are allocated in the current system.

A significant observation was that those in the middle-income group (with monthly household income of $6,001–$10,000) felt “sandwiched”. This group consistently expressed lower fairness levels than other groups for all redistribution approaches, including their most preferred universal, means-tested, which could be a signal to their sentiments of being left out of most government schemes targeted to help the poor, while still having to pay taxes.

People felt it was fairer to pay a bit more for universal, means-tested subsidies and transfers, rather than pay less, through lower taxes, for targeted schemes.

Another important finding was that while the generally perceived fairness of a policy always dropped when people were informed that higher taxes were required to pay for higher expenditures, there were considerable variation among certain subgroups and domains. First, respondents with higher education levels (degree and above) and monthly household incomes ($10,000 and above) had a greater tolerance for higher taxes in return for increased public expenditure. This could possibly be due to their better understanding of trade-offs in public finance and having more financial resources to cope with higher taxes or prices. Second, certain domains still received high level of support for increased expenditure, even taking higher taxes into account. One such area was healthcare: people generally felt that paying higher taxes for more healthcare subsidies was fair. This is probably due to the fact that healthcare is something everyone expects to depend on sooner or later. On the other hand, expenditures on early child education and income support for lower wage groups saw larger relative drops in perceived fairness once higher taxes or out-of-pocket expenditures were mentioned.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, there was a general preference for the universal means-tested approach to allocate public resources in most domains. People felt it was fairer to pay more for universal, means-tested subsidies and transfers, rather than pay less, through lower taxes, for targeted schemes. In other words, people seemed willing to tolerate some inefficiency and costs to themselves if the policy appeals to their sense of fairness.

These insights may inform Singapore policymakers’ understanding of how policies can be designed for greater public buy-in, balanced against the efficiency of more targeted approaches.

NOTES

- Lim Siong Guan, speech at the launch of the Public Relations Academy Conference, 28 June 2002.

- Louise Bamfield and Tim Horton, “Understanding Attitudes to Tackling Economic Inequality” (York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2009), access date 19/02/2013, https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/understanding- attitudes-tackling-economic-inequality.

- A. Park, E. Clery, J. Curtice, M. Phillips and D. Utting, eds., British Social Attitudes: The 29th Report (London: NatCen Social Research, 2012), accessed 19 February 2013, https://www.bsa-29.natcen.ac.uk.

- N. Daniels, Just Health (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008) and J. P. Ruger, “Health, Capability, and Justice: Toward a New Paradigm of Health Ethics, Policy and Law”, Cornell Journal of Law and Public Policy 15 (2006): 403–82, cited in Julia Lynch and Sarah. E. Gollust, “Playing Fair: Fairness Beliefs and Health Policy Preferences in the United States”, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF) Scholars in Health Policy Research Programme, Working Paper Series, WP-47, 2010, http://healthpolicyscholars.org/sites/healthpolicyscholars.org/ les/w47\_lynch. pdf.

- For the purpose of this survey, the targeted approach refers to a selected segment of society receiving bene ts or bearing the costs of a policy. For example, only the low-income group would receive subsidies or only the high-income group would have to pay taxes. The universal, means-tested approach refers to everyone in society receiving the bene ts and bearing the costs, but the amount depends on their needs and abilities. Hence, lower-income citizens would receive more subsidies and pay less taxes, whereas higher-income citizens would receive less subsidies and pay more taxes. The universal approach refers to everyone receiving the same amount of benefits or bearing the same costs regardless of their income levels.

- For details on methodology and questionnaire design, please visit www.cscollege.gov.sg/ethos.

Annex: Methodology and Questionnaire Design

Methodology

The survey’s total sample size was 1,002 Singaporeans aged 20 and above. As there were 3 sets of the questionnaire, each set had a sub-sample of 334. The questionnaires were randomly allocated among the respondents.

A sample of 50 random locations from the survey company’s housing sampling frame was first selected; around 20 respondents were then selected within each random location. The total sample size of 1,002 (each of the three sub-samples was 334 Singaporeans) was selected to closely resemble the demographic profile of Singapore Residents (i.e. age, gender, race, housing type and working status).

Prior to the actual fieldwork, a pilot with 10 Singaporeans was conducted by the survey company to test the readability and process of the survey. The questionnaires were then translated to Mandarin, Malay and Tamil to accommodate respondents who were not proficient in English. The survey was conducted face-to-face at respondents’ homes and the fieldwork was completed within 1.5 months (28 February to 11 April 2014).

Questionnaire design

The questionnaire was designed to present various scenarios in which respondents would be invited to state if the scenario was “fair” or “unfair”. This approach was chosen over asking respondents a fairness question directly, or made to rank options because it made the survey questions more salient and intuitive to answer. For example, instead of asking “Do you think it is fair for the government to fully cover medical insurance premiums for all Singaporeans across different income levels?”, the following scenario was laid out to elicit a response:

Question 7, version A:

Anne and Ben are Singaporeans who need to pay the same amount of hospital bills. They can use hospitalisation insurance to pay the bills. As Singaporeans, the government pays fully for their hospitalisation insurance premiums with no questions asked about their income. Is this fair or unfair?

Using this approach, a set of 18 questions was generated to cover fairness perceptions on taxes, social transfers and benefits, as well as means-testing criteria. Each question had two or three variations (a, b, c versions) to test the respondents’ fairness perception across possible policy options (e.g. targeted, universal, means-tested and universal approaches). Each questionnaire contained only one variation of each question, which resulted in three different sets of questionnaires. Each respondent answered only one questionnaire.

To prevent question order bias, the variations under each question were randomly allocated to each set of the questionnaire, for example:

-

Set A: 1a, 2b, 3b, 4c

-

Set B: 1b, 2a, 3c, 4a

-

Set C: 1c, 2c, 3a, 4b