Randomised Controlled Trials in Policymaking

ETHOS Issue 12, June 2013

Introduction

There is no doubt that public policy should rely on evidence to ascertain whether intervention is likely to work. Historically however, many policy decisions have been dominated by values, interests, timing and circumstances — political realities, in short.1

Proponents of a more evidence-based approach argue for the use of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in public policymaking. They have long been used in healthcare research design: people are selected randomly to receive either the intervention being tested or the standard intervention (as a control group), so that on average all possible causes are evened out across different groups. Today, most new drugs and medical treatments are required to pass an RCT showing that they are more effective than existing medicines before they are cleared for prescription.

In recent years, RCTs have increased in prominence, with Abhijit Banerjee and Esther Duflo pioneering the use of RCTs in development economics.2 Their work, and that of others in related fields, has raised the prospect of RCTs as a means to help policymakers find realistic answers to questions at hand. Policymakers can be better prepared and informed when implementing a new policy intervention, or when evaluating and refining current interventions.

Yet policymaking worldwide —including in Singapore — has yet to enjoy such systematic rigour. Inertia, cognitive bias and ideology often prevent proper randomised trials from taking place. In addition, there are ground issues with RCTs such as ethical concerns and administrative costs that further impede running trials.

How Do We Find Out What Works? Run a Trial

RCTs can play an important role in the rigorous evaluation of how policies actually work in practice. First, theory is often ambiguous on the effects of policy intervention. For example, wage supplements for low-wage earners can result in either more (substitution effect) or less (income effect) working hours. Thus, trials can help shed light on the overall effect of policy interventions. Second, even if the overall direction of a policy effect is known, it is still important to assess the magnitude of its impact. Third, trials can help discover unintended consequences of policy interventions.

In Singapore, a trial conducted by the Ministry of Social and Family Development on the impact of selected activities on active ageing found that adults engaged in some activities had stronger social engagement than the control group. While this may seem rather intuitive, the RCT also provided a way to quantify the extent to which these programmes have actually improved the overall wellbeing of elders. This helps policymakers decide where and how much resources should be channelled, and what policy refinements could be made to achieve the desired outcomes. In other cases, RCTs have also revealed which aspects of a policy have the greatest effect towards desired outcomes.3

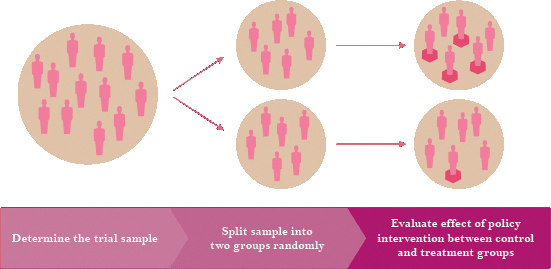

How a Randomised Controlled Trial works

Running a trial involves splitting the study sample into two groups by random lot, one of which (control group) will get the standard intervention, while the other (treatment group) will get the new intervention.

This allows for a more robust and transparent comparison of how effective a new intervention is, compared to doing without it.

In addition, when individuals are assigned randomly and the sample size is large enough, the control and treatment groups can be expected to have the same characteristics. This eliminates the possibility of external factors (e.g. bias in the sample group) that could affect the results.

Trials have also helped uncover false interventions that were believed to be effective. The “Scared Straight” programme in the US was intended to deter juvenile delinquents and at-risk children from criminal behaviour, by exposing them to the realities of a life of crime through interactions with serious criminals in custody. The programme was designed on the assumption that these children would be less likely to engage in criminal behaviour if made aware of the serious consequences. A trial run of the programme showed otherwise: the intervention, in fact, led to higher rates of offending behaviour, while costing the taxpayers a significant amount of money.4

Obstacles in Conducting RCTs and Overcoming Them

Despite the merits of RCTs, it is generally acknowledged that governments are not making the most of their potential in the policymaking process. Many attribute this to the persistence of ideologies, political priorities or habit. There are, however, other real obstacles to running reliable trials, including ethical concerns, administrative challenges of running a randomised trial, institutional capacity and problems of external validity.

Ethical concerns seem to be among the most common obstacles. Many people believe that it is unethical and unfair to withhold a new intervention from people (e.g. the control group) who could benefit from it, even for the purposes of a trial. This is particularly the case where additional money is being spent on programmes that might improve the health, wealth or education of one group. In The Tennessee Study of Class Size in the Early School Grades, researchers faced objections from parents to the variation in the treatment of children.5

In light of these ethical issues, policies that are planned to be rolled out slowly and on a staggered basis present ideal opportunities for public policy experimentation. A very large scale RCT on the effectiveness of the conditional cash transfer programme in Mexico was conducted on the basis of budgetary and administrative constraints, which meant that the programme could not be extended to all eligible communities at the same time. In phases staggered across a two-year period, treatment and control groups were randomly assigned, allowing for robust randomised evaluation of the programme (see story on “The Impact of PROGRESA on Health in Mexico”).

The Impact of PROGRESA on Health in Mexico

PROGRESA combines a traditional cash transfer programme with financial incentives for families to invest in human capital of children (health, education and nutrition).1 In order to receive the cash transfer, families must obtain preventive healthcare and participate in growth monitoring and nutrition supplements programmes.

Approximately 10% (506) of the 50,000 PROGRESA communities were chosen to participate in trials. These communities were randomly assigned to either a treatment group that would receive PROGRESA benefits immediately or a control group that would be given the benefits two years later. The trials showed that the utilisation of public health clinics increased faster in PROGRESA villages than in control areas, with significant improvements in the health of both adult and child beneficiaries.

Notes

- GarGertler, Paul and Boyce, Simone. “An Experiment in Incentive-Based Welfare: The Impact of PROGRESA on Health in Mexico”. University of California, Berkeley, 2001. http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/gertler/working_papers/PROGRESA%204-01.pdf

In Singapore, the Ministry of Education conducted a trial of the new Chinese Language Curriculum in 2006 for Primary 1 and 2 levels. Instead of a full roll-out to all schools, 25 pilot schools were selected to represent an even spread of school types and students’ home language profiles, so that a better estimate of the effects of the new curriculum could be made (see story on “Modular Curriculum for Chinese Language in Singapore Primary Schools”).

In line with recommendations made by the Chinese Language Curriculum and Pedagogy Review Committee, a modular Chinese Language curriculum was piloted at 25 schools in 2006.1 Various aspects of the new curriculum including the modular structure, pedagogical approaches, textbook and activity book, instructional resources and students’ learning outcomes were studied.

Modular Curriculum for Chinese Language in Singapore Primary Schools

In line with recommendations made by the Chinese Language Curriculum and Pedagogy Review Committee, a modular Chinese Language curriculum was piloted at 25 schools in 2006.1 Various aspects of the new curriculum including the modular structure, pedagogical approaches, textbook and activity book, instructional resources and students’ learning outcomes were studied.

Outcomes in terms of teachers’ pedagogical practices and students’ learning from pilot and non-pilot schools were compared. The pilot schools yielded encouraging results and indicated that the curriculum objectives were largely achieved. By the end of 2006, the new curriculum for Primary 1 and 2 was ready for implementation in 2007.

Notes

- “New Chinese Language Curriculum Ready for Implementation at Primary 1 and 2 Levels in 2007”. Ministry of Education, Singapore press release. Singapore: November 15, 2006.

One natural opportunity for RCT is when current policy gives rise to exogenous changes. A study done by Angrist and Lavy6 on the impact of class size took advantage of such a situation. In Israel, schools must open an additional class when they reach a certain maximum number of students per class. Termed the “Maimonides rule”, this resulted in a credible source of exogenous variation for class size research, allowing researchers to conduct RCTs on the impact of class sizes on scholastic achievement, with less concern about ethics or fairness.

Another limitation of RCT adoption is that randomisation can be expensive and administratively challenging. On the ground, complete randomisation is often extremely costly to administer, and may be impossible if the policy has already been rolled out. This is a significant reason why RCTs are often substituted by simple experiments or pilots within a community or locality, even though they lack rigour and reliability and are prone to selection bias. Voluntary participation can exaggerate or distort observed effects because volunteers may be more experienced or more motivated than those who refuse to participate. Policy interventions borne out of studies based on highly self-selective samples can go awry because they do not present a realistic picture of how the intervention will work.

High costs can be overcome. For instance, experiments could be carried out on current policy and outcome data already being collected from routine monitoring systems (whether administrative or survey data). To illustrate: the UK Courts Service and the Behavioural Insights Team wanted to test whether sending text messages to people who had failed to pay their court fines would encourage them to pay prior to a bailiff being sent to their homes (see story on “The Impact of Text Messaging on Fine Repayments in the UK”). The trials were conducted at very low cost as the outcome data was already being collected by the Courts Service, and the only cost was the time taken for the team to design and set up the trial.

Demonstrating the Impact of Text Messaging on Fine Repayments in the UK

The Courts Service and the Behavioural Insights Team carried out two trials to test whether sending text messages to people who had failed to pay their court fines would encourage them to pay prior to a bailiff being sent to their homes.1 The individuals in the initial trial were randomly allocated to five groups. The control group was not sent any message, while the other intervention groups were sent either a standard text or a more personalised message (with the name of the recipient, amount owed or both). The trial showed that text message prompts yield far better payment rates compared to no text prompts.

A second trial was conducted to determine the aspects of personalised messages that were key to increasing payment rates. It ascertained that not only were people more likely to make a payment if they received a text message with their name, but the average value of fine repayments went up by over 30%. This amounted to an additional annual recovery of over £3 million in fines, and eliminating the need for up to 150,000 bailiff interventions annually.

Notes

- Laura Haynes, Owain Service, Ben Goldacre and David Torgerson. Test, Learn, Adapt: Developing Public Policy with Randomised Controlled Trials (UK: Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team, 2012).

Voluntary participation can exaggerate or distort observed effects.

Apart from costs, policymakers often also need to undertake longer-term studies to understand the effects of a policy intervention over time. This poses administrative and logistical challenges (e.g. ensuring participant follow-up). As time goes by, response rates may fall, leading to higher attrition rates, and the probability of contamination (control group having access to the equivalent programme) increases. Trials examining long-term effects of policies therefore need to be carefully planned and mindful of these possible obstacles.7

In situations where randomisation may not be possible, it may still be useful to find alternative ways to randomise the recipients for the purposes of analysis. Researchers evaluating Singapore’s Work Support Programme (WSP) were unable to randomise the selection of recipients into the programme because it had already been implemented. Instead, they randomised the receipt of different versions of the programme (i.e., variations in the amount and duration of assistance) so that the effects of differences in amount and duration of assistance could be reliably tested. This could still provide further insight into “what matters” when WSP recipients try to attain financial independence, sustained employment and earnings.8 In other cases where randomisation is not feasible or the best approach, there are evidence-based tools of similar rigour that might be explored; quasi-experimental research designs that could substitute for RCTs include matched subjects design9 and regression discontinuity design.10

RCTs also require sufficient institutional capacity. In a speech on evidence-based policymaking, Gary Banks (Chairman of the Australian Productivity Commission) argued that “any agency that is serious about encouraging an evidence-based approach needs to develop a ‘research culture’”.11 Nurturing such a culture would involve a range of elements, from establishing evaluation units and achieving a critical mass of researchers to strengthening links with academics, research bodies and institutions working in the field. Such holistic commitment could prove challenging amidst competing priorities and demands on resources in government.

RCTs also suffer from problems of external validity. It is unclear whether the findings from one specific trial can be carried over to another economic and social context. When scaled up, a policy may generate effects that were not picked up in a smaller trial: the local impact of a policy may not be the same as when it is more broadly applied. For example, smaller class sizes may improve learning outcomes in a trial. But when all schools reduce class sizes, there will be an increased demand for teachers. This can cause a change in teaching quality, which may not be accounted for in the trial.

Furthermore, the context of an evaluation (place, time, participants, norms and implementer) may influence the final outcome of the trial. However, these evaluations could still inform decisions on whether or not to implement new policies. They should also encourage governments to replicate the trial in their own countries to verify the results.12

At any rate, the external validity problem is not unique to RCTs — it affects any evaluation derived from studying a policy in a specific context, and is a general problem that remains to be addressed in the social sciences.

Conclusion

Beyond being a powerful tool to evaluate single policy interventions, it is useful to think of RCTs as part of a continuous process of policy innovation and improvement. Trial findings can be built upon to identify new ways of improving outcomes, especially when trials are used to identify which aspect of a policy produces the greatest impact.

In Singapore, government agencies embarking on new programmes recognise the value of RCTs, as evidenced by nascent efforts to conduct trials on new policy interventions. We are not spared from the challenges faced in conducting RCTs, and in some cases, conducting an RCT at the policy level may not even be feasible.

However, there are ways to make the best of the situation and data on hand, such as by looking for alternative ways to randomise, or by using other tools of similar rigour. This is far better than settling for a pilot that is conducted on a self-selective sample based on vicinity or other factors of convenience. Without evidence and robust ways to test the outcomes of interventions, policymakers can only rely on intuition, ideology and inherited wisdom, risking good intentions that produce disappointing or unintended outcomes.13

NOTES

- Gary Banks, “Evidence-Based Policy-Making: What is it? How do we get it?” ANZSOG/ANU Public Lecture Series, Canberra, Australia, February 4, 2009.

- Taking the lead with their work at the Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), Banerjee and Duflo have identified new aspects of the behaviour and needs of the poor, including the way financial assistance impacts their lives. They have also debunked certain presumptions — that microfinance is a cure all, that schooling equals learning and that increasing immunisation rates among the poor is costly. See: Abhijit V. Banerjee and Esther Duflo, Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty (New York City: Persus Book Group, 2011).

- In 2006, the then-Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports (MCYS) embarked on a seven-year study of families placed under the Work Support Programme (WSP) in 2009. The study includes a randomised trial of WSP recipients to understand how differences in the duration and quantum of assistance may affect their capability for self-reliance.

- Laura Haynes, Owain Service, Ben Goldacre and David Torgerson, Test, Learn, Adapt: Developing Public Policy with Randomised Controlled Trials (UK: Cabinet Office Behavioural Insights Team, 2012).

- Frederick Mosteller, “The Tennessee Study of Class Size in the Early School Grades”, The Future of Children 5(1995): 113–127.

- Joshua D. Angrist and Victor Lavy, “Using Maimonides’ Rule to Estimate the Effect of Class Size on Scholastic Achievement”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 114(1999): 533–575.

- Researchers undertaking the longitudinal study to evaluate Singapore’s Work Support Programme put in place measures to minimise attrition, such as requesting contact information of three people closest to the respondent to increase contact points, and providing a token for participation as an incentive to keep respondents in the study. See: I. Y. Ng, H, K. W. Ho, T. Nesamani, A. Lee and N.T. Liang, “Designing and Implementing an Evaluation of a National Work Support Programme”, Evaluation and Program Planning 35(2011): 78–87, doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.07.002.

- Ng, I. Y. H, K. W. Ho, T. Nesamani, A. Lee and N.T. Liang. “Designing and Implementing an Evaluation of a National Work Support Programme”. Evaluation and Program Planning 35(2011): 78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2011.07.002.

- For more information on Matched Subjects Design, visit http://www.education.com/study-help/article/matched-pairs-design-comparing-treatment/?page=2 and http://www.une.edu.au/WebStat/unit_materials/c6_common_statistical_tests/special_matched_samples.html

- For more information on Regression Discontinuity Design, visit http://www.nber.org/papers/w14723.pdf, http://www.socialresearchmethods.net/kb/quasird.php and http://harrisschool.uchicago.edu/Blogs/EITM/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/RD-Lecture.pdf

- See Endnote 1.

- Adrien Bouguen and Marc Gurgand, “Randomised Controlled Experiments in Education”, European Expert Network on Economics of Education (EENEE) Analytical Report, no. 11 (February 2012).

- As Duflo candidly puts it in an interview, RCTs are good news “for people who don’t have a hugely strong view about how anything in particular should work and are willing to apply that mindset but are willing to be proven wrong by the data… By measuring well and showing what the effects are, you get these kinds of realistic answers. When you don’t measure you can always claim something big. From Tim Ogden, “An Interview with Banerjee and Duflo, Part 4”, Philanthropy Action (July 13, 2011), http://www.philanthropyaction.com/articles/an_interview_with_banerjee_and_duflo_part_4