Governance Through Adaptive Urban Platforms: The INSINC Experiment

ETHOS Issue 12, June 2013

Technology companies such as Google, Amazon and Facebook are redefining “customer service”. Every search we make on Google, every book we browse on Amazon, every Facebook post we “Like” or share is stored and analysed to build a customer profile. They predict customer likes and dislikes with uncanny accuracy. Google is able to find the information users are looking for in context. Amazon suggests books that we would enjoy reading. Facebook recommends long-lost primary schoolmates as friends.

These companies are able to do so because they build their services on top of a platform, by which we mean a collection of technologies that support multiple applications. It is interesting to note that the platforms of Google, Amazon and Facebook are all converging technologically while offering a range of different services, from search, online shopping and social networking to video sharing, document sharing, and cloud computing. They seek to expand their user base and increase the number of user interactions on their platforms, because doing so increases their database, which in turn enables them to serve more customers better and improve their bottom lines. Their business model is “One Customer; One Platform; Many Services”.

Like Google’s consumers, citizens also interact with government services regularly, in a variety of ways and in great numbers. Governments are in an enviable position given the breadth of services they offer and the depth of detailed personal data they can collect about their customers: births, deaths and travel movements, income, medical records, educational qualifications, the usage of water and electricity from individuals to households and commercial entities. Unlike Google, however, governments usually offer each service on separate platforms, i.e., they are not integrated. There may be sound regulatory or other reasons for this separation, but it can prevent governments from leveraging data the way Google does in order to serve the public better.

Governments are in an enviable position to offer integrated, personalised and real-time services based on te breadth and depth of citizen data they can obtain.

Integrated Service Platforms in Boston and New York

Boston’s BUMP1 platform allows a citizen to post “glitches” that need fixing; e.g., potholes, broken hydrants, faulty lighting, bad taxi service. This helps authorities to target areas that require the most attention. For example, if data analysis finds that 20% of the potholes in Boston are found to make up 80% of the complaints, the public works department can prioritise the potholes that attract the most complaints for repair.

Similarly, New York’s Office of Policy and Strategic Planning has used public data on carting service licenses to track down illegal dumpers of grease.2

Notes

- http://www.cityofboston.gov/internships/BUMP.asp

- http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/24/nyregion/mayor-bloombergs-geek-squad.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

Fortunately, governments around the world are fast catching up to these opportunities, and are integrating their services into unified platforms. An increasing number of cities, such as Chicago,1 are pursuing predictive analytics platforms that warehouse all the data collected by municipal agencies. Policy Exchange, a conservative think tank in the United Kingdom,2 called on the British Government to set up an analytics capability in the Cabinet Office “to identify big data opportunities and help departments to realise them”.

Such platforms remain largely passive and non-real time, because the data collected by the platform is analysed by public agencies periodically offline. They do not involve the user in a real-time feedback loop. Adaptive platforms, however, feature a tight feedback loop between the platform and the user. Google Maps, for example, adaptively directs users to travel on routes with minimal congestion and hence travel time, based on data from central databases as well as the real-time locations of other smartphones on the map.

There are three elements to an adaptive platform:

- First, they mine the data across a large user base;

- Second, they provide valuable feedback to the users; and

- Third, they affect the state of the system by nudging users to adjust their behaviour in response to feedback.

INSINC: Singapore’s Adaptive Platform for Public Transport

Singapore has been experimenting with an adaptive platform based on the public Mass Rapid Transit (MRT) rail network. The platform is known as INSINC, which stands for “Incentives for Singapore Commuters”, and is provided as an online cloud service at www.INSINC.sg. Launched as a Stanford/NUS trial in January 2012, the platform is supported by Singapore’s Land Transport Authority and SMRT.

Solving the Problem of Traffic Congestion

Transport planners aim to supply sufficient public transport capacity (e.g. buses and trains) in anticipation of long-term projected demand. However, planners are typically less adept in accommodating transient or short-term demand fluctuations, which can occur from time to time. Moreover, purely adding capacity to address short-term peak demand does not always solve the problem: when capacity is added, latent demand moves in to fill it, thus leading to a marginal reduction in peak hour crowding. In Singapore’s context, this “peaking” concept is better understood for road capacity, where it is now generally accepted that road capacity is finite — but it is much less recognised in terms of public transport. Thus, peak demand for public transit must also be managed; capacity addition alone is not sufficient.

Using Incentives: Behavioural Economics and the INSINC Concept

INSINC adds a new option to the transport planner’s arsenal: using incentives to change travel behaviour. Incentives are attractive because they are seen as a win-win solution: commuters are not “penalised” for wrongful behaviour; rather, the system rewards them for exhibiting positive behaviours. Further, since commuters view them favourably, incentives can be deployed incrementally and be customised to the individual, unlike penalties, which for reasons of equity have to be applied across-the-board.

How INSINC Works

INSINC is best described as a frequent commuter programme, similar to an airline miles programme. Its main goal is to shift commuters from peak to off-peak trains.

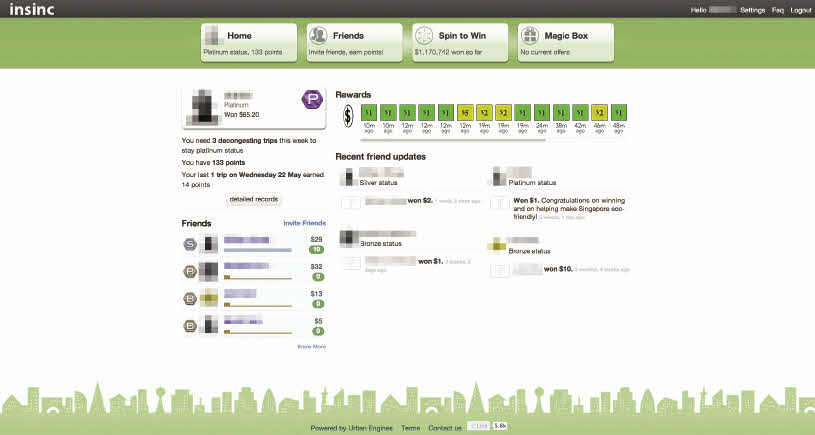

Signing up, Winning Rewards, Inviting Friends

A commuter registers and sets up his INSINC account using the unique identification number of his fare card. Trips made using this card earn credits proportional to the distance travelled, with extra credits for off-peak trips. The credits earned by a commuter are redeemable either at a fixed exchange rate, or for prizes ranging from $1 to $200 in a fun online game — essentially a “self-administered raffle”. This leverages behavioural economics — the general preference of people for a $100 prize at 1% odds over a $1 prize — to induce a larger shift, which in turn improves cost efficiency.

There is a strong social element to INSINC. Participants may invite their friends to join from social networks and email services (Facebook, Gmail, Yahoo! mail, etc.), and they earn bonus credits when their friends sign up. Friends are displayed on a participant’s INSINC page in a “ranking list” style: off-peak commuting friends on top, followed by others.

Personalised Recommendations via the Magic Box

Every Friday at 10am Singapore time, commuters receive a "magic box offer", which is an offer of extra rewards should they achieve behaviour targets the following week. For example, a commuter travelling consistently in the peak hour may receive extra credits for off-peak travel the following week, while a different commuter may earn extra credits for inviting friends; yet another commuter may get extra credits for answering a few survey questions.

Such personalised offers allow administrators to understand a participant's utility function: i.e., a commuter's willingness to exhibit a particular behaviour, measured in monetary terms.

Applying Incentives in a Principled Way

The Stanford Center for Societal Networks1 has been running a series of projects to study the effect of incentives as a way to nudge people to change their behaviour. Their research has uncovered several insights:

- Receiving money is more motivating than avoiding charges — carrots work better than sticks.

- When the stakes are small, a random reward is more appealing than a deterministic reward of the same expected value — a fact underlying lottery systems. Games are an intuitively pleasing, fun and engaging way of conducting lotteries.

- Humans are social animals. Viral adoption, peer comparison and collective spirit are all powerful motivators.

- Fine-grained measurement and data mining allow desired behaviours to be targeted and rewarded precisely. It allows offers to be personalised to users, depending on the negative externality of their behaviour on system efficiency.

Notes

Incentives are attractive because they are seen as a win-win situation.

INSINC: Results and Benefits of Urban Platforms

INSINC has grown at a phenomenal rate since its inception, with about 3,500 participants in January 2012 and doubling its subscription rate every three months. INSINC has over 103,000 registered participants as of 15 May 2013, and does not appear to have reached saturation point. Over 70% of the participants have enlisted through friend invitations. Comparing travel patterns of trips made by participants before and after registration, we have observed shifts from peak to off-peak in the range of 8% to 15%. Those with friends on the INSINC platform shift significantly more: good behaviour appears to thrive on inspiration and competitiveness. The platform has a weekly engagement rate of between 25% and 30% and a monthly engagement rate of over 50%, comparable to mainstream social platforms such as Facebook. However, beyond shifting peak commuters to off-peak, the true utility of INSINC is best expressed in terms of its capabilities as a platform.

INSINC participants, through registration and use of the platform, actually offer up a wealth of personal information, including demographic profiles and commuter logs. This database provides tremendous insights for INSINC administrators, both at the individual and aggregate levels. For example, over 17% of males shift to the off-peak, while only 11% of women do the same. When men shift from the peak, they shift to both pre- and post-peak; women, however, shift primarily pre-peak (possibly because of childcare responsibilities). About 25% of the participants contribute over 90% of peak hour trips; this means that if we can induce these 25% to shift, the marginal impact would be very significant.

We can do so because we know the individual’s propensity to shift. INSINC allows customised testing, as participants are offered different individual payoffs because we know how likely they will shift given a certain payoff: this is the idea behind the Magic Box. With a larger base of users, we would be able to do small group experiments on a large scale, much as Google, Amazon or Facebook do today.

Looking Ahead: Further Applications for Adaptive Platforms

Once INSINC achieves critical mass as an adaptive platform, it would have built up a pool of users who are familiar and comfortable with the “methodology” of INSINC as well as INSINC administrators who can posit outcomes based on past behaviour. Potential applications in a range of public service fields could then open up.

• Health Promotion and Exercise: Using concepts from INSINC, Accenture employees signed up to a programme which gave them points for clocking a certain number of walking steps. The experiment yielded similar results in that employees responded to incentives — monetary and social. More importantly, the experiment demonstrated the viability of a health promotion platform that is adaptive. The platform evolved as employees invited their friends, transacted regularly, and habits of walking started to form. We see the potential to scale such a platform to the national level, given the ubiquity of sophisticated smartphones that already have gyroscopes and location sensors embedded. Indeed, INSINC commuters can be incentivised to get off one station before their destination and walk the rest of the way — to work or home. This would decongest the trains while, simultaneously, promoting physical exercise.

• Municipal Services: Residents often transact with town councils or local governments. These transactions include complaints, requests such as clearance of bulky items, or inquiries. There is potential for a platform to be built around enabling citizens to report faults and file complaints in return for points (these could be monetary, material or reputation points). Such an adaptive platform could also use the concept of gamification and incentives to build desirable community norms and ownership. More active levels of response on the ground would enable the government to capture and analyse data in the backend, and micro-target incentives or messages.

• Energy Conservation: Every home-dweller receives a utilities bill every month. Using incentives, a home-dweller could be nudged to conserve energy. His behaviour can then be used as social proof for other home-dwellers, thus creating an opportunity to cultivate good habits and reinforce energy conservation norms.

Personalised offers allow administrators to understand a participant's utility function: i.e., a commuter's willingness to exhibit a particular behaviour, measured in monetary terms.

Conclusion: Lessons on Designing Adaptive Platforms

The INSINC experiment demonstrates great value for the potential of adaptive platforms in urban settings. As governments build data platforms to serve policy objectives, there are opportunities to develop these platforms further as adaptive ones, amplifying their effectiveness through the tight feedback loops and shaping individual behaviours and norms. Based on the INSINC experience, some insights on how to design an effective adaptive platform have emerged:

- A platform should support a large user base. Platforms with few users will vanish or be absorbed into a larger platform.

- A platform should provide an interesting and useful service. This sounds like a tautology, but it suggests the kinds of service around which effective platforms may be built. For example, birth registries are a statutory requirement — hence they are large — but they are not very interesting or useful on an ongoing basis.

- A platform should have frequent user engagement. Such a platform has the potential to influence highly dynamic societal processes, even ones with which it may a priori have very little or no relationship. Witness the manner in which smartphone-based mapping solutions help with traffic management.

- A platform should be extensible. Platforms should not be over-engineered to suit only one particular application.

- Platforms should evolve in a data-driven fashion. The effectiveness of the Magic Box offers is a testament to the power of mining data to understand the behaviour of fine-grained commuter segments and apply appropriate nudges.

- Platforms induce good social norms. Many online fora have their own social norms and “good behaviours”; for example, good Internet communication is famously termed “netiquette”. As large numbers of users engage with urban platforms, they will create and propagate a new “civic sense”.

Such adaptive platforms have great untapped potential to provide a significant leap in performance in public sector service delivery and cost efficiency, at a resolution commensurate with the individual’s needs and expectations. In doing so, the adaptive nature of such platforms can help the government understand and strengthen its evolving relationship with citizens to a much greater and nuanced degree.

NOTES

- http://www.informationweek.co.uk/big-data/news/government/leadership/chicago-cio-pursues-predictive-analytics/240153231

- http://policyexchange.org.uk/images/publications/the%20big%20data%20opportunity.pdf