Managing Transitions

ETHOS Issue 11, Aug 2012

The Impact of Success or Failure in Making Transitions

Success or failure during a period of significant job changes is a strong predictor of overall success or failure on that job.1 Research has consistently shown that both career-related transitions and events in one’s personal life can be powerful triggers for transformative self and leadership development, because the challenges presented by these transitions provide opportunities for the individual to acquire new skills and beliefs that would help him become more effective.2

However, not everyone is successful in making a transition. Some people may be unwilling to let go of a previous role and its accompanying beliefs and behaviours; others may be unwilling and/or unable to acquire a new role together with the unfamiliar beliefs and behaviours that are necessary for meeting the new demands. By one estimate, over 75% of high-potential leaders experience significant to moderate problems when they move into a new role,3 and transition failures could lead to stress and burnout or a sense of stagnation, derailment and career dissatisfaction.4 ,5 At the organisational level, the cost of a leader who fails to adjust to a transition includes organisational inefficiencies, failure to complete important initiatives or meet important organisational goals, as well as adverse impact on the engagement and development of subordinates reporting to the leader.6

Strategies for Managing Transitions

While organisations could devote more effort and resources to actively help their staff manage transitions, individuals need to take ultimate responsibility for their lives. Greater awareness of the possible transitions that they may face during their working years, the challenges involved in these transitions, and the strategies they can adopt to better manage these transitions, would all help individuals to be more prepared to handle transitions, particularly those which their organisations have little control over and can offer little meaningful support for.

Although the demands of every transition may be different, there are some general strategies that an individual can adopt to enhance transition success in the workplace.

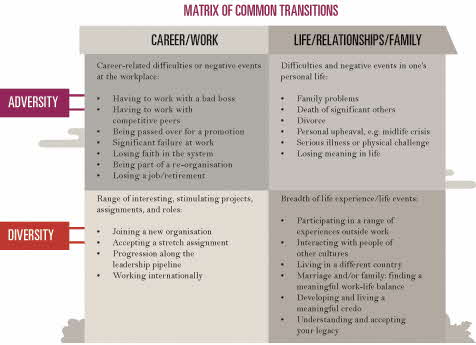

Matrix adapted from Dotlich, Noel & Walker, 2004; list of transitions collated from Charan, Drotter & Noel, 2001; Dotlich et al., 2004; Ruderman & Ohlott, 2000.

Positivity

According to Schlossberg,7 adaptation to a transition is the interaction of three sets of variables: an individual’s perception of the transition, the characteristics of the individual, and the characteristics of the pre- and post-transition environments. Positivity means that the individual perceives the transition as a positive event and is ready to embrace the challenges and risks and make the necessary adaptations. Being developmentally ready, that is, having “the ability and motivation to attend to, make meaning of and appropriate new knowledge into one’s long-term memory structures”,8 facilitates learning from work and life experiences in general. More specifically, perceiving the transition as an opportunity for greater learning and growth would help one accept a higher level of challenge during the transition.9 Bunker10 similarly points out that people who adopt a learner response to a change are more likely to be comfortable with the change and to have a high capacity for change. Such positivity is particularly essential when the pre- and post-transition environments are significantly different, which represents a more intense transition that requires a greater degree of new learning. Positivity may be more difficult when the transition is perceived to be undesirable. What is helpful in these instances is to see the transition from a broader perspective, which can provide a greater degree of objectivity about the situation and serve as a reminder that negative events can provide useful leadership development experiences.11

People who adopt a learner response are more likely to have a high capacity for change.

Positivity also entails being resilient, instead of allowing self-doubt or defeatism to hamper one’s ability to handle the challenges of a transition.12 While there is an element of optimism to positivity, this is optimism that is grounded in reality. In one study, individuals who approached career change planfully and realistically cited better experiences of the transition and perceived themselves to be coping better than did individuals who ignored signs of change or reacted unrealistically.13

Clarity about Role Requirements and Internalisation of New Identity

Transition failures often occur because people do not understand their roles when they move to a new position.14,15 Without this information, it will be difficult for them to make sense of their new environment and adjust accordingly. An individual anticipating or going through a transition in the work context needs to find out as much as possible about the nature of the role, the job content, how the role fits into the organisational context, and what others expect of him in this role, and obtain validation from his supervisor for his definition of the job.16-19

Beyond a cognitive understanding of new role requirements, the individual needs to reflect on what the transition means for him at a more personal level. A transition often challenges an individual’s sense of identity because questions about who he is, who he is becoming, what his values and ideals are, and how he matters and belongs to the group or community are likely to surface during this time. To make sense of the situation, the individual may have to revisit his self-identity and make readjustments where necessary.20-22 This examination of identity not only applies to work or leadership identity, but may also extend to one’s personal and family identities.23 A successful adjustment to a transition means that the individual has internalised a new role identity and reworked his life story such that he can meaningfully link who he is and who he will become.24

Internalising a new role identity is an important part of the transition adjustment process because the discoveries and reflections that the individual makes during this time help him to acquire new perspectives about how he can contribute and add value in his new role, and these transformations in his thinking will bring about sustained behavioural changes.25,26 To the extent that this new identity is accepted by others, it would also facilitate his social integration.27

Commitment to Learning

Another key theme in the experiences of individuals going through transitions is about gaining competence in meeting the demands of a new role. Individuals often feel vulnerable and incompetent when they are making a transition because the demands of the new role will always differ from the demands of the previous role, and the familiar beliefs, knowledge and well-honed skills that have helped the individuals to succeed in the previous role are no longer adequate and in some cases, the current capabilities may no longer be useful. Yet, during times of stress, individuals are even more likely to fall back reflexively on the skills and strategies which have been tried and tested in the past, even though they may no longer be effective.28

At this point, clarity about role requirements, coupled with an accurate assessment of one’s current strengths and limitations and reflexive responses to challenges, can help the individual to identify what needs to be learnt to close the competency gap. Broadly, career-related transitions may require the individual to close skills gaps in fulfilling new responsibilities as well as knowledge gaps in terms of technical or business knowledge, customer or market knowledge, organisational norms and power-relations, procedures or approaches for completing work tasks.29-32 Researchers also note that different work and life experiences offer different learning opportunities,33,34 and even transitions that represent an adversity, such as failure at work or loss of significant others, can facilitate learning and development and bring about greater leadership maturity.35

What is important during the transition is that the individual accepts personal responsibility for the situation and puts in the effort to quickly and efficiently learn what he does not know. Besides identifying his learning agenda, he has to plan how he can best address these gaps (whether it is through tapping on the knowledge of specific persons, hands-on experience, critical analysis, or other methods).36,37 He must also exercise self-discipline to consciously work at those areas that he needs to improve in or do more of.38

A successful adjustment to a transition means that the individual has internalised a new role identity.

Accepting personal responsibility is particularly helpful for transitions that represent adversity because it allows the individual to engage in constructive self-examination, which increases awareness about his limitations and vulnerabilities. It also encourages him to reflect on how he can be a more effective leader.39

Delivering Results

Once the individual has made sense of his new role and gained greater knowledge about his new situation, he has to map out his key priorities and strategies in the coming months, define performance standards, and then ensure he achieves the desired results.40,41 The strategy needs to be mapped to the particular characteristics and challenges of the situation.42 In addition, although it is important to strategise about longer term goals, it is also important that the individual identifies some immediate focal points where he can quickly achieve tangible results. Securing such early wins in his new role would help establish his credibility and set up a virtuous cycle which would facilitate further success.43

What is important during the transition is that the individual accepts personal responsibility for the situation and puts in the effort to quickly and efficiently learn what he does not know.

Building and managing key relationships will facilitate the individual’s ability to deliver results. One key relationship that has to be managed is the individual’s relationship with his supervisor. He has to understand his supervisor’s style and agenda, and negotiate success for himself by clarifying mutual expectations, seeking the necessary resources, and working in ways that would support his supervisor’s agenda. He also has to build a strong network of people who can support him, and to create coalitions with stakeholders that are critical to his success.44,45

Renewal and Support

Besides a steep learning curve, individuals undergoing a transition are likely to be under pressure to deliver results quickly.46 The emotional and cognitive challenges posed by transitions mean that they are stressful periods and during these times, the individual has to find ways to maintain a sense of balance in his life. This may include engaging in re-energising activities (such as sports or hobbies) or seeking a quiet place of refuge where he can temporarily escape and recharge.47 He also needs to set aside time to get adequate rest and sleep, and to have the mental space to reflect.48

The individual may also need to seek additional support to help him get through the transition, to prevent burnout and to provide renewal.49 During this period, his social networks (such as family, friends and other community groups) and his professional networks of peers, superiors or mentors, may be able to provide both emotional and practical support as well as serve as role models or offer additional insights or alternative perspectives that can help him cope with the situation.50 In fact, a study showed that social support mechanisms, such as having regular feedback from their supervisors or peers, improved people’s ability to learn from extremely challenging work experiences.51 Such support would help enhance transition success.

Conclusion

While we may not always be able to plan what transitions we have to face, we are able to calibrate our responses to these transitions. These strategies could help an individual manage the challenges of transitions and reap their potential benefits.

NOTES

- Watkins, M.D., “Picking the Right Transition Strategy”, Harvard Business Review (January 2009): 47–53.

- Significant life changes can challenge basic beliefs and assumptions, requiring us to transform how we perceive and interpret ourselves and the world around us, and to develop new priorities, learn unfamiliar skills, behaviours and patterns of interpersonal reactions so that we can transit into the new role or situation. (Ibarra and Barbulescu, 2010; Isopahkala-Bouret, 2008; Sargent and Schlossberg, 1988).

- Shaw, R.B., and Chayes, M.M., ”Moving Up: Ten Questions for Leaders in Transition”, Leader to Leader (2011), 39–45.

- Dotlich, D.L., Noel, J.L., and Walker, N., Leadership Passages: The Personal and Professional Transitions that Make or Break a Leader (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2004).

- McCauley, C.D., and Lombardo, M.M., “Benchmarks: An Instrument for Diagnosing Managerial Strengths and Weakness”, in Measures of Leadership, eds, in K.E. Clark and M. Clark (West Orange, NJ: Leadership Library of America, 1990), 535–545.

- Byham, T.M., Concelman, J., Cosentino, C., and Wellins, R., Optimising Your Leadership Pipeline (Development Dimensions International, Inc., 2007).

- Schlossberg, N.K., “A Model for Analysing Human Adaptation to Transition”, Counselling Psychologist 9 (1981): 2–18.

- Hannah, S.T., and Lester, P.B., “A Multilevel Approach to Building and Leading Learning Organisations“, The Leadership Quarterly 20 (2009): 34–48.

- DeRue, D.S., and Wellman, N., “Developing Leaders via Experience: The Role of Developmental Challenge, Learning Orientation, and Feedback Availability”, Journal of Applied Psychology 94 (2009): 859–875.

- Bunker, K.A., Responses to Change: Helping People Manage Transition (Greensboro: Center for Creative Leadership, 2008).

- See Endnote 4.

- See Endnote 4.

- Ebberwein, C.A., Krieshok, T.S., Ulven, J.C., and Prosser, E.C., “Voices in Transition: Lessons on Career Adaptability”, The Career Development Quarterly 52 (2004): 292–308.

- Charan, R., Drotter, S., and Noel, J., The Leadership Pipeline: How To Build The Leadership-Powered Company (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001).

- Hill, L., “Becoming the Boss”, Harvard Business Review (2007): 49–56.

- See Endnote 14.

- Ibarra, H., and Barbulescu, R., “Identity as Narrative: Prevalence, Effectiveness, and Consequences of Narrative Identity Work in Macro Work Role Transitions”, Academy of Management Review 35 (2010): 135–154.

- Sargent, A.G., and Schlossberg, N.K., “Managing Adult Transitions”, Training and Development Journal 42 (1988): 58–60.

- See Endnote 3.

- Avolio, B.J., and Hannah, S.T., “Developmental Readiness: Accelerating Leader Development”, Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research 60 (2008): 331–347.

- See Endnote 17.

- Louis, M.R., “Career Transitions: Varieties and Commonalities”, Academy of Management 5 (1980): 329–340.

- Musselwhite, W.C., and Dillon, L.S., “Timing, For Leadership Training, Is Everything”, Personnel Journal 66 (1987): 103–110.

- See Endnote 17.

- See Endnote 20.

- Ibarra, H., Snook, S., and Guillen Ramo, L., Identity-Based Leader Development (Fontainebleau: INSEAD, 2008).

- See Endnote 17.

- Berglas, S., and Baumeister, R.F., Your Own Worst Enemy: Understanding the Paradox of Self-Defeating Behaviour (New York: Basic Books, 1993).

- Ibarra, H., and Hunter, M., “How Leaders Create and Use Networks”, Harvard Business Review (2007): 40–47.

- Isopahkala-Bouret, U., “Transformative Learning in Managerial Role Transition”, Studies in Continuing Education 30, No. 1 (2008): 69–84.

- See Endnote 18.

- See Endnote 3.

- McCall, M.W., “Recasting Leadership Development”, Industrial and Organizational Psychology 3 (2010): 3–19.

- Ruderman, M.N., and Ohlott, P.J., Learning from Life: Turning Life’s Lessons into Leadership Experience (Greensboro: Center for Creative Leadership, 2000).

- See Endnote 4.

- See Endnote 3.

- Watkins, M.D., The First 90 Days: Critical Success Strategies for New Leaders at All Levels (Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2003).

- See Endnote 1.

- See Endnote 4.

- See Endnote 14.

- See Endnote 3.

- See Endnote 1.

- See Endnote 37.

- See Endnote 1.

- See Endnote 37.

- Chari, S., “Handling Career Role Transitions with Confidence”, The International Journal of Clinical Leadership (2008): 109–114.

- See Endnote 4.

- See Endnote 46.

- See Endnote 18.

- See Endnote 4.

- See Endnote 9.