Fostering Mutually Constructive Engagement in a Globalised Singapore

ETHOS Issue 11, Aug 2012

Following the worldwide failure of both “big government” (welfarism) and“market fundamentalism” (neoliberalism), commentators across the ideological spectrum have identified “society” as the answer to the challenges of globalisation.1 Studies of social capital have grown in popularity — as has the work of Robert Putnam, who posits a positive relationship between good governance, economic prosperity, and strong and engaged civil society.2 Yet globalisation, which has challenged faith in the state and the market, also challenges the cohesion of society. It does so not only by widening income inequalities,3 but also by introducing unprecedented levels of cultural and ideological diversity into a populace.4

Singapore society has become much more cosmopolitan as a result of globalisation. The number of highly-skilled Singaporeans living abroad increased from 36,000 in 1990 to 143,000 in 2006.5 The experiences of these Singaporeans, the presence of foreign nationals as both subjects of and actors in local civil society, and access to global media, all contribute to Singaporeans framing issues not just in local but also in transnational terms.6 Non-governmental organisations (NGOs) are increasingly forming links with others abroad, and are playing an active role across the region and even the world.7

The challenge of building a cohesive and pluralist polity comprising people of different formative experiences, globalised reference points, and diverse rationalities calls for a mutually constructive relationship between government and civil society. Singapore has a well elaborated model of governance to manage racial and religious diversity. Civil society’s perception of government, however, can seem to be marked by a concern for discerning the “out of bounds” markers for non-state actors such as NGOs. This presupposes a mutually exclusive relationship between government and civil society, and leads the former to believe that the government should simply “get out of the way”. This is not only unhelpful but dangerous, since “more” civil society may very well yield illiberal and prejudicial outcomes.

More importantly, this view of government-civil society relations ignores the fact that government can play a role in shaping a civil society that will contribute positively towards pluralist ends. Republican theories of civil society ascribe to government the role of establishing the rules and values within which civil society should function. Above all, the state is responsible for fostering patriotic individuals who partake equally of the liberties and responsibilities of citizenship.8

State and Civil Society: A Symbiotic Relationship

Danish political theorist Per Mouritsen has argued that Scandinavian countries tend to enjoy a “symbiotic complementarity between state and civil society”.1 Illustrating the crucial role of government in the formation of civil society, he contrasts the civil society of the Weimar Republic that produced the Nazi state, with the civil society that underpins the post-Communist Eastern European states. Mouritsen argues:

There must be reasonable and operative laws before people will learn to respect them, working institutions before national solidarity, and rights before anyone would wish to be a citizen. The first step towards civil society is a civil state — difficult as this is.2

One author Mouritsen discusses at length is none other than Alexis de Tocqueville who wrote, almost two centuries ago, that “civil associations therefore facilitate political associations; but, on the other hand, political associations singularly develop and perfect civil associations”.3 De Tocqueville argued that it was through participation in the work of government that individuals learn how to live and work with each other. “Political associations,” De Tocqueville argued, “can therefore be considered great schools, free of charge, where all citizens come to learn the general theory of associations”.4

Notes

- Mouritsen, Per, “What’s the Civil in Civil Society? Robert Putnam, Italy and the Republican Tradition”, Political Studies 51 (2003): 657.

- See Endnote 1, p. 658.

- Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000), Vol. 2, Part 2, Chapter 7, p. 496.

- See Endnote 3, p. 498.

The question, then, for Singapore, is how government can encourage and constructively engage with the NGO sector. To begin, government needs to become more comfortable with open contestation and the apparent “disorder” associated with civil society. Governance by consensus certainly has its merits, but such consensus must not only emerge but appear to emerge from the reconciliation rather than the curtailment of contestation. Public officers know that the best solutions emerge from sensing the disparate perspectives, interests and needs of a diverse society.9 Yet, there continues to be a widespread perception that government is wary of civil society, and that it muffles dissent or dismisses critics.10 The government could more clearly signal its willingness to engage with controversial or contrarian ideas in order to encourage NGOs’ trust in government. Such trust encourages NGOs to approach public agencies in a spirit of cooperation rather than defensiveness.

A mutually exclusive relationship between government and civil society is not only unhelpful but dangerous.

To facilitate this, government could provide more platforms where different interests can meet each other, and thus design conversations that forge consensus. Public engagement already occurs on many policy issues, and this has encouraged a more cooperative relationship between all involved. However, civil society-government relations in Singapore are still often framed in a petitionary framework, wherein advocates approach public agencies without having to face and consider the perspectives of others who may have opposing views. Moreover, NGOs often complain about being talked to rather than talked with. Facilitating dialogue between diverse groups will enable them to constructively engage with issues in fuller knowledge of the choices and trade-offs involved. The ensuing familiarity can also encourage public officers and activists to view each other not as institutions or interests but reasonable people of goodwill who can validly hold divergent views on important questions.11

In the same vein, government should foster greater transparency of information. Beyond the often-stated benefit that it fosters trust between government and citizens,12 transparency of information also empowers citizens to engage in issues more critically, responsibly, and effectively.13 For example, NGOs and volunteer welfare organisations (VWOs) have asked for more and better information on domestic violence to help them design programmes and assess their impact.14 The importance of transparency in fostering critical citizen engagement is all the more crucial in a time when social and other online media constrain government’s ability to shape the public agenda. While this places a burden of data collection and communications on public agencies, it has the benefit of promoting greater public understanding of the constraints underlying policy options and implementation.

Finally, government should continue to uphold the plural and secular nature of the public sphere. Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong stated in 2009 that the Government “hold\[s\] the ring so that all groups can practise their faiths freely without colliding with one another in Singapore”.15 Indeed, the Government has played this role in several public controversies in recent years.16 While activists in Singapore civil society may be motivated by religious convictions, the state’s role as referee helps ensure that those advocating their cause in a pluralistic society must communicate their ideas in terms that non-coreligionists can engage with.

The corollary to a plural and secular public sphere is the non-politicisation of race and religion. That race and religion inform but do not determine policy preferences was underlined in the Government’s response to calls by four local Muslim groups in 2002 for Singapore to oppose a war on Iraq. Member of Parliament Zainudin Nordin rejected the groups’ depiction of the war as a religious issue, while Yaacob Ibrahim, the Minister in charge of Muslim Affairs, insisted that Muslims would not respond monolithically to political events.17

The role that civil society can play in fostering constructive engagement with government is implied in the above recommendations. First and foremost, civil society should recognise that government is a necessary partner in the formation of a pluralistic public sphere that complements particularistic interests and the public good. There are certainly historically valid reasons for Singapore civil society to be wary of government. However, a cautionary note needs to be taken from the experience of Eastern Europe, where a reflexive suspicion of government born out of years of authoritarian rule left societies vulnerable to the market power of capital in the post-communist years. Activists need to be careful about adopting neoliberal assumptions about the iniquity of regulation, and approach government with suggestions on how governance can be improved rather than removed.

Second, civil society needs to approach government in good faith and with patience and understanding. Just as activists want to be spoken with rather than to, public officials want to be conversed with rather than harangued. Government’s effort to understand civil society needs to be mirrored by better comprehension on the part of activists of the goals and constraints within which public agencies work. Activists should therefore acknowledge multiple versions of successful advocacy, and continue to engage with government even if they fail to achieve everything they seek.18 If and when problems arise in engagement and collaboration, activists need to offer constructive criticism rather than complaints.

In conjunction with the above, it is important to emphasise that increased understanding of the work of government will better equip activists to realise their goals. L. David Brown and Jonathan Fox, writing about transnational activism vis-à-vis the World Bank, advise NGOs not to think of “large actors as monolithic institutions that present united fronts to external challenges”. Instead, they argue, activists should recognise that such institutions “include staff with a wide range of political and social perspectives” who can yield “advice, information and support”.19 This does not mean that activists should play one agency against another. Rather, working with public agencies can help NGOs to better align their particular goals with state ones and develop strategies to better communicate their perspectives to policymakers.

It remains the prerogative of elected officials to choose among policy options and take responsibility for any resulting trade-offs.

Finally, civil society should acknowledge the agency and autonomy it enjoys in the public sphere today. This should enhance its confidence and willingness to approach government as a partner rather than a supplicant. Over a decade ago, Simon Tay exhorted civil society to believe, against the “veto of power” enjoyed and exercised by government, that “citizens \[could\] organise civil society on their own terms”.20 He pointed to the flourishing of Eastern European civil society under communist rule to illustrate the possibilities in this imagination. The political, social, and technological conditions of today’s Singapore make Tay’s exhortation a reality to be recognised. The Lien Foundation, for example, advocates and pursues improvements in the care of the terminally ill and young children with developmental needs — areas that are under-served. Similarly, AWARE’s shadow reports to the United Nations Committee on the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) challenge the Government to do more to combat gender-based stereotyping in policy.

Scholarship and commentary on state-civil society relations in Singapore needs to train its lenses less on the state and more on the realised and potential agency of civil society. There is also room for further research into how government can systematically and successfully engage NGOs in order to better design and implement public policy. Activists should respect the fact that it remains the prerogative of elected officials to choose among policy options and take responsibility for any resulting trade-offs. In making those trade-offs, however, the Government should systematically and transparently engage with Singapore’s burgeoning civil society to make better sense of a decision-making ecology that is increasingly critical and complex. Both sides need to engage with each other in a fashion that both respects diversity and forges cohesion. This can only happen if both government and civil society see each other not as antagonists and competitors in the public sphere, but rather as equally fertile sources of ideas and passion for making Singapore a better home for all.

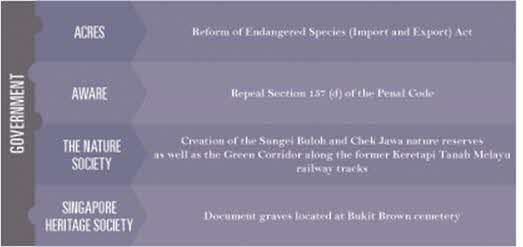

Working Hand in Hand

There have been many examples of successful engagement between public agencies and NGOs on social issues. In 2006, advocacy by the Animal Concerns Research and Education Society (ACRES) led to the reform of the Endangered Species (Import and Export) Act.1 In 2011, AWARE’s activism led the Government to repeal Section 157 (d) of the Penal Code.2 The Nature Society’s lobbying played a crucial role in the creation of the Sungei Buloh and Chek Jawa nature reserves as well as the Green Corridor along the former Keretapi Tanah Melayu railway tracks. The Government is currently working together with the Singapore Heritage Society to document graves located at Bukit Brown cemetery.3

Notes

- See ACRES – Our Achievements, https://acres.org.sg/about-acres/our-achievements/ (accessed July 6, 2012).

- “MinLaw to Stop Sexual History Being Used Against Rape Victims”, The Straits Times, November 25, 2011.

- “More Hands on Deck for Bukit Brown”, The Straits Times, December 11, 2011.

NOTES

- Samuel Bowles and Herbert Gintis point out that the idea of society is attractive to the left because of its emphasis on collective action and to the right because it stresses non-governmental solutions to market failure. See Bowles, Samuel, and Gintis, Herbert, “Social Capital and Community Governance”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 112, No. 483, Features (November 2002): F419–F436.

- Putnam, Robert, Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton, NJ; Princeton University Press, 1993); and Putnam, Robert, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

- This issue has received much attention in Singapore, with the national budget for 2012 emphasising social transfers and other forms of aid for disadvantaged Singaporeans.

- Arjun Appadurai argues that migration and “electronic media” have allowed people to imagine identities beyond “the cordon sanitaire of local and national media effects”, thereby challenging “the continued salience of the nation-state as the key arbiter of important social changes.” See Appadurai, Arjun, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of of Globalisation (Minneapolis, Minn.: University of Minnesota Press, 1996),

- Porter, Michael, Neo, Boon Siong, and Ketels, Christian, Remaking Singapore (Boston: Harvard Business Publishing, 2009).

- Local NGO Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) has called upon the Government to sign international conventions on migrant workers and domestic workers. Another NGO, Maruah, has been active in promoting an ASEAN Declaration of Human Rights.

- For a study of the international connections among activists for migrant workers, see Lenore Lyons, “Transcending the Border: Transnational Imperatives in Singapore’s Migrant Worker Rights Movement”, Critical Asian Studies 41, No. 1 (2009): 89–112. Additionally, several groups took part in the United Nations’ review of Singapore’s compliance with the Convention Eliminating All Forms of Discrimination Against Women in 2011.

- Mouritsen, Per, “What’s the Civil in Civil Society? Robert Putnam, Italy and the Republican Tradition”, Political Studies 51 (2003): 650–668.

- For further information on how dissent, debate, and diversity yield the most creative ideas and effective solutions, see Snowden, David J., and Boone, Mary E., “A Leader’s Framework for Decision Making”, Harvard Business Review, November 2007; and Lehrer, Jonah, “Groupthink: The Brainstorming Myth”, The New Yorker, January 30, 2012.

- For some recent critical views of the Singapore Government’s engagement with civil society, see Chong, Terence, “Civil Society in Singapore: Popular Discourses and Concepts”, Sojourn, 20, No. 2 (2005): 273–301; Ho, Khai Leong, Shared Responsibilities, Unshared Power: The Politics of Policy-Making in Singapore (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press, 2003), 332–368; Lee, Terence, “Gestural Politics: Civil Society in “New” Singapore”, Sojourn 20, No. 2 (2005): 132–154; and Lyons, Lenore, “Internalised Boundaries: AWARE’s Place in Singapore’s Emerging Civil Society”, in Paths Not Taken: Political Pluralism in Post-War Singapore, eds, Michael D. Barr and Carl A. Trocki (Singapore: NUS Press, 2008), 248–263. Highly respected New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd referred to Singapore as a “polished, deeply authoritarian police state”. See Dowd, Maureen, “From Gallipoli to Singapore”, The New York Times, July 19, 2011.

- See Maniam, Aaron, “A New Tribe for New Geographies: Reasonable People of Goodwill”, New Geography, February 8, 2011.

- See Florini, Ann, “Behind Closed Doors: Governmental Transparency Gives Way to Secrecy”, Harvard International Review (Spring 2004): 18–21; and “Introduction: The Battle Over Transparency”, in The Right to Know: Transparency for an Open World, ed. Ann Florini (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 1–16.

- Cherian George has argued that “limited access to official information constrains the volume and quality of citizen participation”. See George, Cherian, “Control-Shift: The Internet and Political Change in Singapore” in Management of Success: Singapore Revisited, ed. Terence Chong (Singapore: ISEAS, 2010), 266.

- The Society Against Family Violence commissioned an International Violence Against Women Survey in 2010 because of a lack of consistent and comprehensive data on the problem in Singapore. See also Association for Women Action and Research, “General Recommendation 19: Violence Against Women”, CEDAW Shadow Report, May 2011, pp. 153–154.

- Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, National Day Rally Speech 2009, 16 August 2009

- Following a leadership tussle in a local NGO when then Deputy Prime Minister Wong Kan Seng reiterated that “keeping religion and politics separate is a key rule of political engagement” in Singapore. See “Exercise Restraint, Mutual Respect, Tolerance”, The Straits Times, May 15, 2009, and Azhar Ghani and Gillian Koh, “Not Quite Shutting Up and Sitting Down: The Singapore Government’s Role in the AWARE Saga” in The AWARE Saga: Civil Society and Public Morality in Singapore, ed. Terence Chong (Singapore: NUS Press, 2011), 42.

- “Attack on Iraq Would Be a ‘Security Issue’”, The Straits Times, September 5, 2002.

- An instructive example can be seen in how women’s groups have continued to work with the Government to improve the management of domestic violence even though the 1997 amendments to the Women’s Charter did not deliver everything they asked for. At the same time, public agencies have demonstrated commitment to assisting individuals not covered by the amendments by using existing laws and mechanisms to protect victims as best as they can.

- Brown. David L., and Fox, Jonathan, “Transnational Civil Society Coalitions and the World Bank: Lessons from Project and Policy Influence Campaigns”, The Hauser Centre for Nonprofit Organisations and The Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University, Working Paper No. 3 (1999), p. 12.

- Tay, Simon S.C., “Towards a Singaporean Civil Society”, Southeast Asian Affairs (1998):253.