Leadership Across Generations

ETHOS Issue 10, Oct 2011

INTRODUCTION

In recognising workforce diversity, social scientists have not only emphasised cultural diversity but also generational differences. The current workforce comprises several generations and at least four cohorts have been identified, each possessing different characteristics from the next. For the first time, the multi-generational workplace is a reality, and the age range of employees in many organisations is widening as people retire later and work for longer.

While social scientists have recognised generational differences as an important aspect of workforce diversity, the literature in the field have tended to focus on how best to manage so-called Gen-Ys. At the same time, the multi-generational workplace raises questions about the changing nature of leadership itself.1 What implications will generational differences have on the practice of leadership, and what will they mean for the development of future leaders? These were some of the questions our recent study sought to answer.2

Singapore's Multi-Generational Workforce

While the precise time-frames may vary, experts generally agree that there are four distinct generations at present:

- Traditionals (Matures) — born between 1909 and 1945

- Boomers — born between 1946 and 1964

- Generation X (Xers) — born between 1965 and 1979

- Generation Y (Gen Y, Millennials or Nexters) — born after 1979

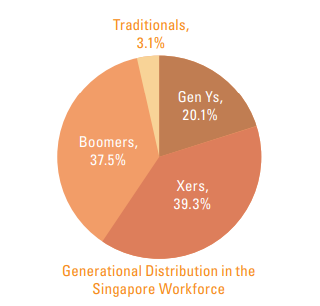

Of the approximately 3 million in the Singapore workforce today, approximately 3% are Traditionals, 38% Boomers, 39% Xers, and 20% Generation Ys.

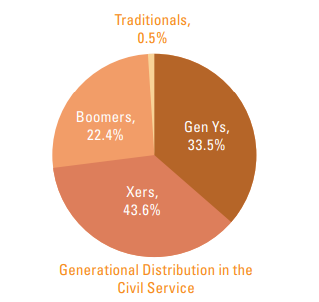

Of the 74,000 employees in the Singapore Civil Service, 0.5% are Traditionals, 22% Boomers, 44% Xers, and 33.5% Generation Ys.

GENERATIONAL DIFFERENCES IN LEADERSHIP

If different generations might be regarded as cultural sub-groups, and leadership theory suggests that culture shapes how people view and practise leadership, then it follows that generational differences in leadership might reasonably be expected. Our research suggests five shifts in leadership style that could be related to generational differences:3

• Individualistic versus Collective.

Newer generations appear to have more of an individualistic focus compared to the more collective orientation of the older generations. It seems that newer generation leaders tend to be more competitive and assertive, compared to older generation leaders who tend to adopt a more communal form of leadership. In our focus groups, Gen Ys described themselves as more self-interested and ambitious. This is manifest in their relative reluctance to take up their share of team tasks, their weighing up of personal gain before accepting roles or responsibilities and their impatience to see immediate returns for themselves. The argument that newer generations have a more individualistic leadership style seems to contradict popular literature that refers to Gen Y as being more team-oriented. They may engage in teamwork but are they good team players? Our focus group data seems to indicate that the newer generation of Singapore leaders are very accustomed to working in teams as a result of their education, but may tend to interpret things through the lens of personal gain rather than the common good.

"…my generation has low emphasis on values… maybe 70% to 80% of those who want to be leaders [do so] because of the rewards… They are more impatient about things and try to gain personal recognition more than to share rewards with their team mates."

— Gen Y Public Service Employee

• Conservative versus Risk Orientated.

Newer generation leaders, having grown up in a world of rapid change and technological revolutions, appear more comfortable with fast changing environments and are more willing to take risks and consider novel approaches in their leadership. In contrast, older generation leaders tend to be more conservative, relying more on predictability and maintaining the status quo. With a lower concern for social norms and greater levels of self-esteem, newer generations may be more equipped to generate out-of-the-box suggestions that they are confident of promoting.

"I was really struck by the difference in her worldview and the willingness to question and challenge assumptions a lot more rather than just take things as a given…this whole openness to new ideas with less concern that the decisions taken now are going to impact my organisation or my country…The older ones amongst us would be weighing [these] more heavily."

— Boomer on Gen Y

• Increasing Intensity and Pace.

Given their openness to risk, the newer generations seem to be more fast-paced and intense in their exercise of leadership. They tend to be perceived as operating with more energy, intensity and passion, while older generations are seen as more likely to maintain a calmer, lower-key, understated stance — with more emphasis on interpersonal impact. Compared to the older generation's world of steady progression and paced achievement, those of the newer generation are accustomed to a world of immediate access, instant feedback and rapid outcomes. While it is possible that the younger generation in the workplace is not any more achievement-oriented than young adults of past generations, they seem to be more demanding for the immediacy of outcomes, and this often manifests as impatience or abruptness in leadership. This "leadership impatience" could stem from generational differences in work values, personality and other factors. There is an indication that the newer generations are more competitive, ambitious and results driven, more self-assured and more opportunistic. Status matters to them and they are eager to seize opportunities.

"I suppose that she's a lot faster, absorbs ideas a lot faster than maybe the Boomer generation and some in the X generation, she moves a lot faster, [is] able to whip up things very quickly, highly energetic…"

— Gen X on Gen Y

• Big-Picture Capabilities but Short-Term Focus.

Whilst the younger generations are supposedly more inclined towards broader-level thinking, they also seem to operate on shorter timescales. This apparent contradiction might be the function of a difference between capability and preference. This is conceivable, given that the newer generations grew up in a more globalised world of not just interacting systems and diverse views, but also one that has a high rate of change, high product design turnover, and a strong emphasis on speed. The new generations might be able to see more quickly and grasp a more complex inter-related world — expressed as an aptitude for bigger-picture and even longer-term thinking. Yet, they have not seen things last for very long and are used to instant results. The younger generation's short-term focus could also reflect their view of organisational commitment — compared to the older generations, they have a more short-term view of their time with an organisation.

"They are very impatient, or have a very short attention span. So they might start on one project and be very excited about it and then they realise 'Maybe we can't do this sort of thing' and then they'll move onto the next thing and be very excited about that."

— Gen Y on Gen Y leaders

• Sources of Authority.

Generations appear to vary in their sources of authority with some real consequences for how they lead. Older generations have a higher respect for those in authority as compared to new generations who are less concerned with authority and hierarchy. The younger generations have grown up in a climate where it is culturally more acceptable to question authority. Their developmental context has been one dominated by post-modern and pluralistic worldviews, with no one seen to possess absolute "right" answers. Many organisations are becoming flatter and younger leaders may perceive influence as deriving primarily from competence and knowledge. Given these differing sources of authority, the older generation leaders can be seen to exercise leadership along lines of hierarchy, viewing leadership influence as generally positional. On the other hand, the newer generations are more likely to respect and also exercise leadership based on capability, competency and expertise, rather than rank.

"[My experience of] all the Boomer bosses I've reported to [is that] it's more formal, in terms of the relationship… and it's a bit more directive rather than discursive." "There is an unspoken expectation that you must respect me, because I'm your boss… and I didn't get to this position for nothing."

— Gen Y on Boomer boss

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF FUTURE LEADERS

If leadership styles are shifting along generational lines, what can we do to bring out the best in leaders of different generations? Our research suggests a few key priorities:

• Developing the moral dimension of leadership.

With the shift towards a more individualistic leadership stance, there is the danger that forms of narcissistic leadership4 could become more evident in newer generations. Over the past decade, there has been growing attention on this issue of the narcissistic leader. Moccoby5 proposes that through development, leaders with narcissistic inclinations can capitalise on their strengths, and learn to manage the darker side of leadership. Leadership programmes, emphasising deeper understanding and the moral responsibility of leadership, can combat narcissism and help develop future leaders.

In his seminal book, Leadership, Burns6 speaks of responsibility of leadership — to elevate others to a higher sense of performance, fulfilment, autonomy and purpose. Leadership development has to expand a leader's concept of leadership: to include the moral dimension, to move leaders beyond a focus on self, to a focus on contributing to others and a wider purpose. In effect, leadership development should help individuals embrace the social and moral dimensions of "good" leadership

• Increasing self-awareness in leaders.

Studies have associated the newer generations with higher self-esteem, assertiveness and lower need for social approval. These characteristics enable a sense of leadership confidence, but could also affect their ability or willingness to acquire a realistic picture of themselves. In contrast, effective leaders must be able to appreciate their true capabilities and weaknesses, as well as their impact on the organisation and the people they are leading. Thus, leadership development may need to focus on cultivating a greater understanding of self in the context of leadership.7

With hierarchy- or position-based authority becoming less accepted by the newer generation of employees, leaders of all generations will have to understand what gives legitimacy to their leadership. They will have to develop a keen appreciation of their strengths (i.e. knowledge, abilities, skills, values, beliefs) and limitations, and take them into consideration when influencing others.

• Watchfulness and mindfulness in leadership.

If the newer generation prefers to exercise a more intense, quick-paced and immediacy-focused leadership, development interventions may need to provide the needed space and time for leaders to slow down and reflect on their influence. In its unmanaged state, a quick-paced leadership style tends to favour action over reflection, whereas both are needed for the exercise of effective leadership. Leaders may need to cultivate the ability to reflect while in the midst of action. As an intervention, leadership coaching can help to build this capacity by modelling the process of reflection and action — individuals can learn to be more mindful of their leadership in the moment, rather than falling back on instinctive behaviours.

• Communicating respect, value and inclusion.

There is a fair degree of empirical agreement between the generations when it comes to what they expect from their leaders. At the top of the list, all generations seek leaders that are able to empathise and care, and who are able to engage them in a vision of the future. Communication that inspires and engages usually contains two elements, one relating to boldness of vision and the other relating to how much the listener is included and involved in that vision. While boldness and confidence can put newer generation leaders in good stead to inspire, the more individualistic and impatient side of their leadership could lead to the exclusion of others. Learning to frame goals and messages in ways that communicate respect and value for others enables leaders to better inspire and engage. For leaders, leadership development should help build awareness in framing interactions, helping them communicate and interact in ways that include the goals, needs and empowerment of others.

• Developing leaders as coaches.

Our research suggests that older generation leaders are keen to develop their staff and younger generation leaders are keen to learn. However, we also found that the preferred learning styles differ across generations. Older generation leaders adopt a more didactic style of development that does not match the more questioning and experimenting learning style of the younger generations — who are used to a more learner-centred experience, like to experiment, are impatient to put learning into practice, and have the self-confidence to come up with some of the answers themselves. Senior and middle management may want to cultivate coaching skills, which can offer their younger counterparts a facilitated way of finding their own solutions to work-based challenges and developing capabilities to work independently and effectively.

• Building leaders that enable leadership.

While narcissistic leadership is reluctant to share focus and power with others, hierarchy-based leadership concentrates leadership power at the top. Both styles tend to disempower others. Yet leadership that enables others to lead is needed in a complex world where no one can know nor act across the full picture.8 Leadership development needs to help leaders embrace a model of leadership that de-emphasises the "heroic" mode of leadership, where vision is monopolised, and focuses instead on harnessing the diverse perspectives, experiences and strengths of others. Leaders who can learn to feel comfortable with not being in the centre, but are open to let others take the lead, will be more successful at creating yet more generations that are capable and equipped to lead.

THE GENERATIONAL CHALLENGE

Both our focus group research and current literature on the workplace have given us a better appreciation of how the different generations lead and what they expect of leadership. From this, we have begun to make conjectures about the developmental needs of leaders from different generations, both now and in the future. We are mindful of the limitations of our study — more research is required for us to be confident that these are generalisable findings.

Nevertheless, the generational phenomenon is one that leaders and leadership development practitioners should take note of. Social scientists theorise that due to the increasing rate of change, generational cycles are becoming shorter and shorter. In the past, distinct generational traits would take 20 or so years to emerge in the workforce, but the present generations have emerged in around 10 to 15 years. If this trend is true, then we may possibly see more than four different generations making up the workplace of the future. Inevitably, generational differences will continue to affect how leadership is conceived of, identified, developed and practised, and by extension, the impact it will have on organisational and societal outcomes.

This article is based on a research report co-written with Jo Hennessy of Roffey Park Institute.

NOTES

- In a Harvard Business School's Working Knowledge article in 2007, Jim Heskett posed the question: "How Will Millennials Manage?", http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/5736html

- This article is based on the findings of a research study undertaken in 2011 by Goh Han Teck of the Centre for Leadership Development, Civil Service College, and Jo Hennessy of Roffey Park Institute. The full research report can be accessed at www.cld.gov.sg

- Scholarship exploring the relationship between generations and leadership is sparse. However, we were able to draw on available studies as well as findings from a focus group study that we had conducted. We also extrapolated from research on generational differences in values, work perception and personality. Our findings are exploratory and indicative rather than conclusive, but provide a useful way of navigating and interpreting inter-generational work interactions.

- With regard to organisational leadership, narcissism has been defined as a "nonpathological (i.e. normal) personality dimension that involves a self-centered perspective, feelings of superiority, and a drive for personal power and glory" (Galvin et al., 2010). See Galvin, B. Waldman, D and Balthazard, P., "Visionary Communication Qualities as Mediators of the Relationship between Narcissism and Attributions of Leader Charisma", Personnel Psychology, 63 (2010), pp509–537

- Maccoby (2004) in the Harvard Business Review, states that "many leaders dominating business today have... a narcissistic personality. That's good news for companies that need passion and daring to break new ground... but can be dangerous for organisations". See Maccoby M., "Narcissistic Leaders: The Incredible Pros, the Inevitable Cons", Harvard Business Review, 82 (2004), pp92–101

- Burns, J. M., Leadership (NY: Harper & Row, 1978)

- Recent leadership development programmes already incorporate tools such as 360 degree feedback, personality assessments, and action-feedback modules to provide the platform for leaders to detach from themselves, gain perspective, and develop the humility needed for continuous learning.

- Follett (1924) has argued that "the most essential work of the leader is to create more leaders." In her book, Creative Experience, she states that "leadership is not defined by the exercise of power but by the capacity to increase the sense of power among those led". See Follett, M. P., Creative Experience (New York: Peter Smith, 1924). 1951 reprint with permission by Longmans, Green and Co.

FURTHER READING

For the complete list of references, please refer to the full research report at www.cld.gov.sg

- Arsenault, P.M., "Validating Generational Differences: A Legitimate Diversity and Leadership Issue", Leadership & Organization Development Journal (Vol. 25 Issue 2), pp124–141

- Cennamo, L., and Gardner, D., "Generational Differences in Work Values, Outcomes and Person-Organisation Values Fit", Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23 (2008), pp891–906

- Conger, J., How "Gen X" Managers Manage, (2001). In Oseland, J., Kolb, D., and Rubin, I. (Eds.) The Organizational Behavior Reader (Seventh Edition), pp9–20. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall

- Han-Yin Chang, J., "The Values of Singapore's Youth and their Parents", Journal of Sociology (Vol. 46 Issue 2, Jun 2010), pp149–168

- Jurkiewicz, C. L., and Brown, R. G., "GenXers vs. Boomers vs. Matures", Review of Public Personnel Administration, 18(4) (1998), pp18–37

- Kabacoff, R.I., Stoffey, R.W., "Age Differences in Organisational Leadership", Paper Presented at the 16th Annual Conference Of The Society For Industrial And Organisational Psychology, San Diego, CA., 2001.

- Kowske, B. J., Rasch, R., and Wiley, J., "Millennials' (Lack of) Attitude Problem: An Empirical Examination of Generation Effects on Work Attitudes", Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(2) (2010), pp265–279

- Kuijsters, F., Harnessing the Potential of Singapore's Multi-Generational Workforce, Tripartite Alliance for Fair Employment Practices (TAFEP), Singapore (2010)

- Lyons, S., "An Exploration of Generational Values in Life and at Work", Dissertation Abstracts International, 3462A (UMI No. AATNQ94206) (2004)

- Mason, C. and Brackman, B., Educating Today's Overindulged Youth: Combat Narcissism by Building Foundations, Not Pedestals (Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2009)

- MCYS and NFC Singapore, State of the Family Report 2009 (Singapore, 2009)

- Ministry of Manpower, Report on Labour Force in Singapore (2009)

- Sessa, V., Kabacoff, R., Deal, J. and Brown, H., "Generational Differences in Leader Values and Leadership Behaviors", The Pyschologist-Manager Journal, (10)1 (2007), pp47–74

- Sirias, D., Karp, H. B., and Brotherton, T., "Comparing the Levels of Individualism/Collectivism between Baby Boomers and Generation X", Management Research News, 30 (2007), pp749–761

- Smola, K. W., and Sutton, C. D., "Generational Differences: Revisiting Generational Work Values for the New Millennium", Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23 (2002), pp363–382

- Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. R., and Lance, C. E., "Generational Differences in Work Values: Leisure and Extrinsic Values Increasing, Social and Intrinsic Values Decreasing", Journal of Management, 36(5) (2010), pp1117–1142

- Twenge, J.M., Generation Me: Why Today's Young Americans are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled – And More Miserable than Ever Before (New York: Free Press, 2006)

- Tzuo, P-W., "The ECE Landscape in Singapore: Analysis of Current Trends, Issues, and Prospect for a Cosmopolitan Outlook", Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education, 4(2) (2010), pp77–98

- Zemke, R., Raines, C. and Filipczak, B., Generations at Work: Managing the Clash of Veterans, Boomers, Xers, and Nexters in Your Workplace (USA: AMACOM, 2000)