The End of the World (Economy) as We Know It

ETHOS Issue 06, July 2009

Many economists have described the current economic and financial crisis as the most severe economic recession since World War Two. The crisis has indeed had far-ranging consequences: oncemighty banks and financial institutions have evaporated; major industries are experiencing significant consolidation; thousands of factories all over the world have shut down, and millions of workers have lost their jobs. Some economists have even speculated that the world was poised for a second Great Depression.

It is still too early to determine if the global economy has indeed seen the worst of the downturn as there are simply too many uncertainties that could destabilise any sort of recovery. However, it has become increasingly clear that the global economy will not revert to its pre-crisis status quo.

The years leading up to the financial crisis were marked by very benign economic conditions leading to structural imbalances in the global economy. At the global level, the developed economies saw strong growth in credit growth and private consumption, while the level of savings plummeted.1 Emerging economies redirected their excess savings to finance consumption in developed economies. This cycle reinforced trade interdependence between the G3 nations (US, Japan and the European Union) and emerging Asian economies and meant that the Asian economic growth became more, rather than less, dependent on G3 growth.

It has become increasingly clear that the global economy will not revert to its pre-crisis status quo.

The current financial and economic crisis has unravelled this intertwined relationship, which the historian Niall Ferguson has described as “Chimerica”.2 Consumption in the US has fallen, perhaps for the foreseeable future.3 Exports from Asia to the developed countries have collapsed. Singapore has been affected severely, with its economy expected to experience its largest contraction since 1965. To date, Singapore’s economic success has largely been attributed to the openness of its economy and its concentration on activities which largely serve G3 demand. But with the unravelling of “Chimerica” bringing long-term change to the global demand landscape, Singapore, along with much of Asia, is likely to face significant challenges in the post-crisis future.

LEGACY EFFECTS FROM THE CRISIS: TIPPING POINTS FOR THE WORLD

The crisis of 2008–2009 will have at least four legacy effects that could permanently alter the global demand landscape.

- Rising public debt in the US, Japan and Europe has escalated with the high cost of recovery fiscal spending. If these countries do not offer viable and sustainable solutions to reduce debt levels in the longer term, investors’ confidence in assets denominated in these currencies could diminish. In any case, investors would also be wary that high levels of public debt now could lead to high levels of taxation later. Reduced foreign appetite for G3 assets (in particular US assets) will impair these governments’ abilities to invest in areas such as education, infrastructure and social safety nets, reducing their long-term economic potential.

- Increased government intervention in the financial sector may stifle the innovation necessary for wealth creation and the financing of the real economy. Over the long run, private consumption and growth levels may be muted if access to credit is restricted.

- Creeping protectionism could reduce the overall level of global trade and affect the main mechanism that has supported Chimerica’s prosperity. Blatant forms of protectionism, such as tariff wars, seem less likely. But more subtle forms of protectionism, embedded as clauses in many fiscal stimulus plans, may hinder the free flow of trade too.

THE CHANGING LANDSCAPE OF GLOBAL DEMAND: POSSIBLE SCENARIOS

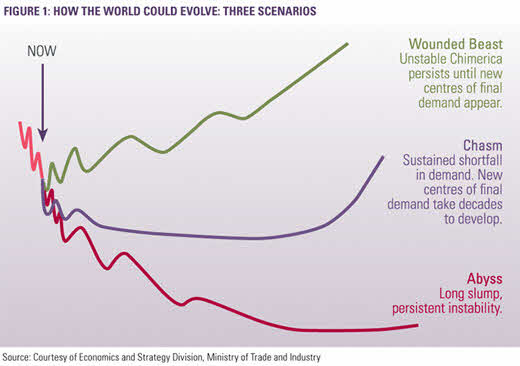

The interplay and depth of these legacy effects will determine the likelihood and extent of revival in the growth engines of Chimerica. While the current crisis has certainly increased the range of possibilities facing the world economy over the next ten to twenty years, we can extrapolate these legacy effects to derive three possible scenarios for the future of the global economy.

• Scenario 1 : Wounded Beast

In this scenario, the world emerges relatively unscathed from the economic crisis of 2008–2009 as coordinated government efforts succeed in stabilising the global financial system. Financial innovation, in turn, manages to outpace the tightening in regulation, allowing households and firms to attain easy access to credit. Consumer and business confidence are restored in the major developed economies, and the exportled “Chimerica” engine revives.

The pick-up in export earnings accelerates the urbanisation process in many emerging Asian economies, resulting in larger numbers joining the urban middle class in Asia. While wealth and buying power increase in these urban centres, the pressures associated with urbanisation, such as infrastructure shortages, also intensify. The demand for raw materials and other resources to support infrastructure grows strongly, but reduced investments in supply during the 2008–2009 downturn create severe upward pressures on resource prices. In addition, speculative activity, occasional supply disruptions and seasonal shortage add to the volatility in resource prices.

This scenario is not a return to a stable status quo. A quick revival of Chimerica means that there will be less will to deal with the structural imbalances that led to the crisis in the first place. The persistence of these imbalances and the intensification of demand on limited resources and commodities increase the likelihood of asset bubbles and crashes, and volatile, unstable growth over the long run. Business cycles, which have already become shorter over the last ten years, will shrink even more. In this world, Singapore, as a small and vulnerable open economy, will have to deal with the impact of a volatile, unstable global macroeconomic environment.

• Scenario 2: Chasm

A lack of international coordination and political will delay the process of economic recovery. Conservative lending practices become entrenched in the commercial banking sector, and credit growth to the private sector and households slows down. A global demand shortfall results as savings rates in the G3 permanently rise with the protracted downturn. Consequently, trade flows are significantly reduced with the fall in G3 demand. Creeping levels of protectionism further inhibit Asia’s ability to tap into G3 demand. The emergence of new and more insidious forms of protectionism occurs as governments are pressured to take actions with mass appeal in stimulating the economy.

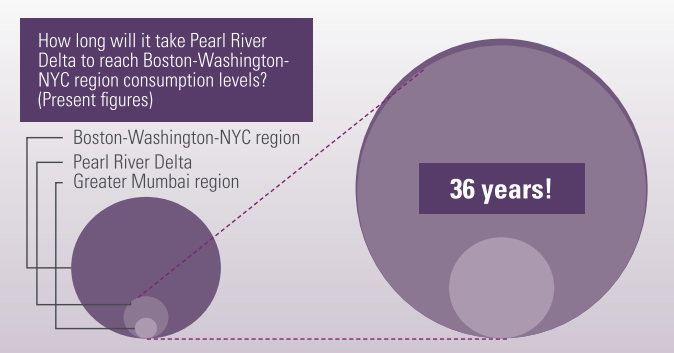

In response to both diminished G3 consumption demand and more restricted market access, Asian governments step up public spending and focus on building up domestic demand. Domestic consumption in Asia, however, will need several decades of growth before it can fully replace G3 as a final source of demand. Global growth therefore slows down considerably, below its long-term potential.

• Scenario 3: Abyss

In the “Abyss”, international recovery efforts fail to contain the adverse effects of the financial and economic crisis. The global economy stagnates for a prolonged period of time, akin to a “Great Depression II”. The protracted nature of the downturn causes deficit governments in the developed economies to exhaust their arsenal of fiscal and monetary tools. Public debt burdens rise to unstable levels and prevent G3 governments from enacting key longerterm structural reforms.

With both public and private sector spending diminished, unemployment rates soar to historic highs. Political instability in many countries mounts. Fears of more job losses to foreigners feed social and political unrest amongst the public; governments are pressured into implementing a massive slew of protectionist measures that eventually lead to a complete breakdown in existing trade architectures. With world trade stalled, the export-led model of growth in Asia collapses. Economic activity stalls in these nations and government expenditure becomes the primary driver of growth in the region. Economic growth will eventually resume, but it will take several years of persistent effort from Asia, as well as extraordinary coordination across governments, to restart the engines of growth again.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SINGAPORE

All three scenarios present significant challenges for Singapore. Against this backdrop, Singapore would need to address three main themes of Resilience, Survival and Relevance to secure its continued economic progress. In the “Wounded Beast”, Singapore would need to develop deeper resilience to resource shocks and shorter business cycles to cope with heightened economic volatility. Muted G3 consumption growth as in the “Chasm” and the “Abyss” suggests that Singapore would need to develop new capabilities to survive a shortfall in G3 demand. Finally, the reduced relative importance of G3 final demand will require Singapore to stay economically relevant to Asia as economies in the region seek to jump-start their domestic demand.

NOTES

- In 2006, the American personal savings rate was -0.6%, an indication that the average US consumer was spending more than they were earning

- Ferguson, N. and Schularick, M., “’Chimerica’ and the Global Asset Market Boom”, International Finance 10 (2007): 215-239.

- The Great Depression altered the spending habits for at least one generation of Americans.