Rethinking Incentives for the Downturn

ETHOS Issue 06, July 2009

Good times can obscure many mistakes. In a boom market, companies may be more lenient towards poor performance and be less inclined to enforce strict performance management systems. In crunch times, many companies do the opposite, and impose stricter or more punitive measures on all employees regardless of performance. Mediocre performers are unlikely to see the need to change while high performers—seeing no return on their discretionary effort—may leave. Hence, employee engagement suffers at a time when the company needs it most.

Employers may be less concerned about employees leaving them during a downturn. However, when good times return, disengaged employees are more likely to jump ship at the first opportunity, just when recovery for the firm becomes possible. Conversely, when employers adopt a long-term view of engaging their employees during a downturn, they will be rewarded with increased loyalty and motivation when the next wave of growth arrives.

The extended period of market growth in Singapore, and indeed in Asia, meant that many employees were accustomed to receiving some sort of bonus and annual salary increases, and may have come to regard these bonuses as a right rather than as a reward for organisational success. With the economic crisis limiting salary budgets, how can managers avoid the money trap and ensure that their staff continues to be motivated and engaged?

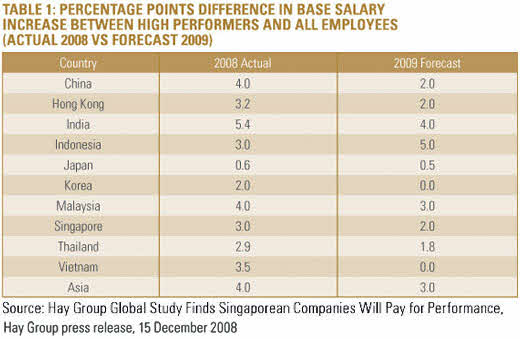

In a spot survey of 516 public, private and government organisations in Asia conducted in November 2008, Hay Group found that Asian companies were using their salary budgets more strategically to reward performance— paying an average of 66.7% more in base salary increases to their high-performing employees compared to all other employees. At the high end, Malaysian, Hong Kong and Singaporean companies surveyed had doled out an average of 60% more in base salary increases to their star performers in 2008 (Table 1).

Certainly, a robust performance management and reward system is critical to success in a downturn. As always, it is important for organisations to clearly define, communicate and recognise what good performance looks like, and to appropriately portion rewards based on differentiated performance (as well as ensure that poor performance is identified and addressed).

Yet appropriate reward and recognition does not have to equate with spending. Employees work for more than money: they work to get training and career development, to make a valuable contribution, and because they enjoy contributing to a common vision and culture. Managers should understand what it is that their employees truly value and focus on improving these, even if (and especially when) financial rewards are being squeezed.

We believe that in order to retain key staff, organisations must resist the temptation to use ever higher salaries as their primary employee retention tool. Ironically, employees who are attracted to jobs only because of high salaries during the boom years (as was common in the banking and financial sectors) will also tend to leave for the same reasons during a downturn. Instead, employers should focus on increasing employee engagement and developing better support systems that enable their employees to succeed.

NOT JUST PAY, BUT ENGAGE AND ENABLE!

Research from Hay Group Insight suggests that an increasing number of organisations enjoy high levels of employee engagement, yet nonetheless struggle with performance issues.

Motivation is only potential energy until it is well harnessed. While employees may feel committed to organisational success, they may nevertheless lack the conditions to channel their efforts productively and effectively.

Getting the most from motivated employees requires that organisations support them in being successful. Employees must not only be engaged, by shared goals, but also be enabled for optimal performance.

Hay Group Insight has found enabling of employees embraces two key components. The first is an optimised role which requires that employees be effectively matched to their jobs, such that their skills and abilities are effectively utilised.

The second is a supportive environment, which involves providing people with the resources they need (for example, time, information, tools and equipment) and removing barriers to getting the job done (such as red tape, or tasks that don’t add value).

By considering both employee engagement and employee enablement, research by Hay Group Insight suggests that there are four distinct groups of employees within a typical organisation (Figure 1).

- Effective employees are both highly engaged and well supported for success. In these ideal circumstances, employees are most likely to be high achievers.

- Ineffective employees lack both engagement and support and are understandably likely to struggle in their job roles. Their poor performance and morale can quickly become a drain on the organisation and others around them. The “vocal few” many often fall within this group.

- Frustrated employees (which may account, on average, for 20% of all employees) represent lost opportunities for their organisations. These employees are aligned with the organisation’s direction and are enthusiastic about making a difference but are nonetheless held back by jobs that do not suit them or work environments that get in their way. Managers are often surprised when such people leave as they appear to be highly engaged employees.

- Detached employees are in roles that suit them reasonably well, and find themselves in a broadly supportive work environment. But for various reasons, their levels of engagement with organisational objectives and task requirements are insufficient to make them optimally effective. This group is often populated with individuals willing to do what is needed to meet their objectives, but no more.

What these employee types make clear is that both engagement and enablement are necessary to provide an optimal climate for effective employees. Take away either strong support structures or high levels of staff engagement and you end up with either frustrated or detached employees. What is worse is when both support and engagement are lacking: employees become ineffective and often a drain on overall morale.

If key talented employees are leaving after all the effort put into engaging them, the secret may lie in balancing out the effort with employee enablement.

Consider these numbers: frustrated employees represent as much as one third of the Asian workforce with only 16% of them believing that they are effective in their jobs. Despite being well engaged by their employers, the frustration of these employees largely stems from a lack of empowerment and professional development. This is in contrast to a similar Hay Group Insight study conducted in the UK, which found that only 21% of the UK employees were feeling frustrated and two out of every five employees considered themselves effective workers (Table 2).

The highest percentage (35%) of Asian employees was found to be detached. They are the ones who will only perform the minimum of what is needed to meet their objectives, and no more. What is worrying with these detached employees, despite the high level of training they have received, is that 60% of them intend to leave their organisations the minute someone makes them a marginally better offer.

So if key talented employees are leaving after all the effort put into engaging them, it may well be that they have not been able to convert their enthusiasm into effective action on the job.

Singaporean organisations that focus only on engaging and motivating employees may ironically be missing out on getting the best possible performance, even from committed employees. In a downturn, both effective engagement and enablement are critical to retaining the talent that organisations will need when the upswing inevitably returns.