Reinventing Singapore’s Electronic Public Services

ETHOS Issue 04, Apr 2008

In 1997, Singapore took bold steps to make public services available through electronic means. Electronic public services were seen as a strategic initiative to enhance Singapore’s readiness to plug into an increasingly complex and networked global economy, and as a means to achieve dramatic improvements in service delivery standards, by harnessing the efficiencies and synergies of emerging information and communications technology. By the end of 2001, more than 1,600 public services were offered online and made accessible through the Internet 24/7, from anywhere in the world. Guided by three e-Government Master Plans,1 Singapore has built up significant understanding and capabilities within the Public Service to leverage electronic service delivery channels to its advantage.

In the past decade, the Public Service has won many international awards and accolades for its e-Government efforts, and is even beginning to export its knowledge and expertise in electronic service delivery. This is a solid achievement that has put Singapore at the forefront of e-Government rankings worldwide. But is this enough? There is clear recognition that the rapid pace of change, a savvier generation of citizens and businesses, and the interconnectedness of public needs will put yet greater demands on the Public Service and the e-infrastructure it has put in place to deliver its core services.

FROM ONLINE SERVICES TO INTEGRATED GOVERNMENT

Singapore’s success has been due in no small part to its nimbleness and adaptability to a changing environment. Decentralisation and autonomy have enabled public agencies to be quick and decisive. But this has also brought about fragmentation, resulting in loss of systemic efficiency and economies of scale. More importantly, there could be sub-optimisation at the whole-of-government level.

This is especially pertinent given the increasingly multi-faceted and inter-related nature of public needs. The Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority could be very efficient in registering a new company, but the company could not start work if our telecommunications infrastructure takes a long time to wire up. In order for our trade and logistics industry to thrive, related agencies such as the sea ports, airports, maritime authorities and customs and have to work together to maintain seamless traffic and inter-connectivity.

In the initial years of Singapore’s e-Government effort, there was an urgency to make public services available online. Public service agencies were strongly encouraged to establish a presence in cyberspace—this resulted in a widespread proliferation of corporate websites, many of which carried little more than basic information about the organisation’s mandate and portfolio of services. In parallel, the eCitizen Portal established opportunities for agencies in charge of related functions to offer their services as an online package for the convenience of customers. This approach was initially focused on front-end bundling of information and basic application and query activities.

However, efforts are now being made to achieve true service integration, through the redesign of business process and flow-through for related public services across different agencies. For instance, an original process might be removed or simplified, such as when another agency has already undertaken necessary steps for validation.

Also under review is the strict delineation between websites that offer government content and those that offer commercial content. The new consumer wants to receive a range of holistic services readily from a single location, regardless of whether the service is of governmental or commercial origin; he also wants these services delivered to him on-demand in an engaging and refreshing manner, with service standards comparable to those of the best available commercial online services in the world.

Progressively, public agencies are partnering with the private sector to provide government information and services together with relevant commercial content on commercial portals. With the introduction of the Public-Private-People Integration (3Pi) approach in 2005, government projects have started looking into opportunities to collaborate across the public and private sectors in order to deliver a holistic range of services with radical improvements and synergies.

Mindef’s miw.com (subsequently replaced by NS Portal2) and LTA’s One.motoring3 are forerunners in this effort, with government owned but privately run portals delivering trusted public services alongside rich commercial offerings of relevance to NSmen and motorists respectively. In 2006, IDA also outsourced its MyeCitizen personalised portal, allowing the private sector to bring more vibrancy into the service through introduction of useful commercial services such as Travel Buddy and Moving House.

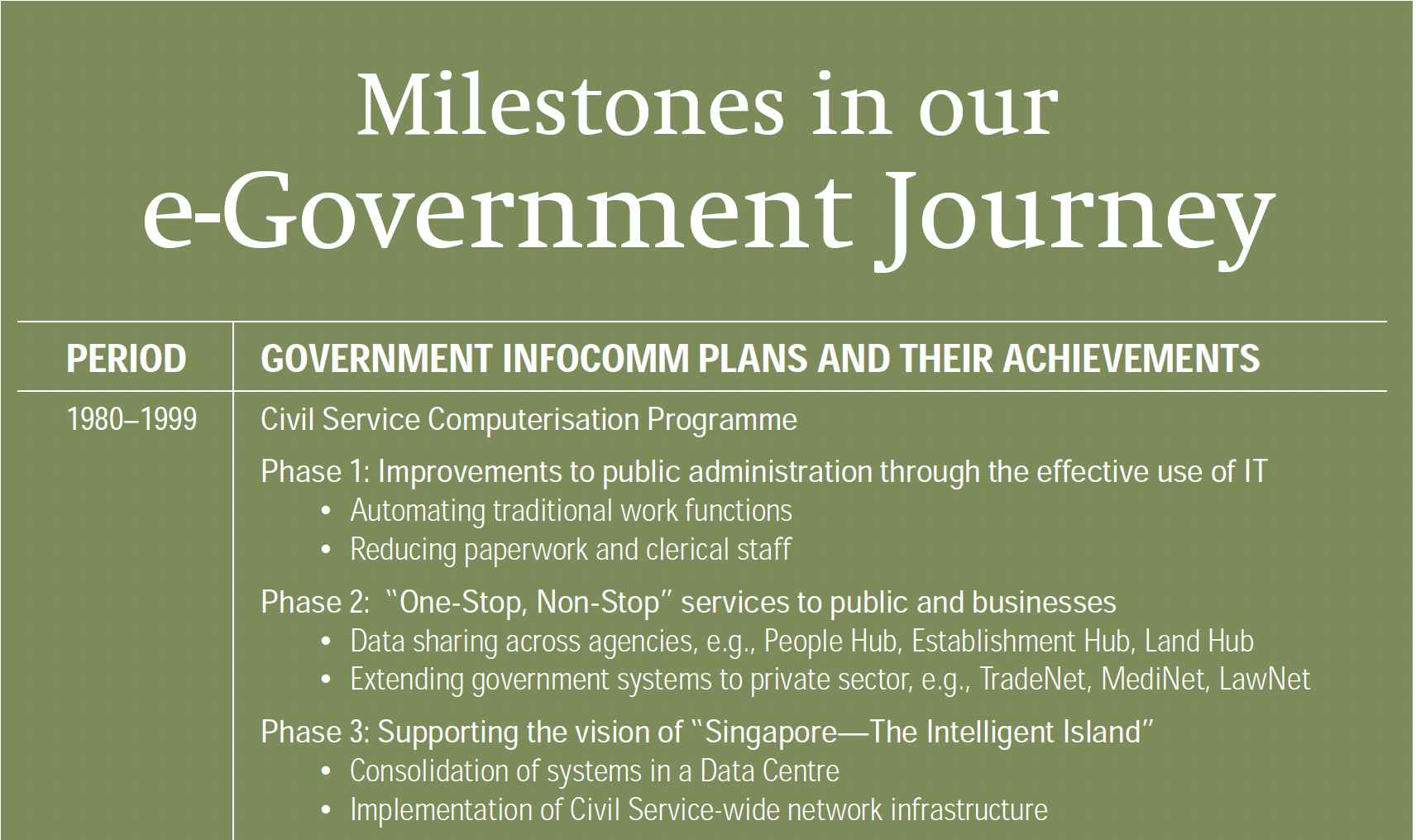

Milestones in our e-Government Journey

Government projects have started looking into opportunities to collaborate across the public and private sectors in order to deliver a holistic range of services with radical improvements and synergies.

THE SERVICE IMPERATIVE FOR CHANGE

Dramatic changes in the nature of public service delivery have been enabled by the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) revolution in the past decade. Yet they are not—and should not be—motivated by technological change. Instead, they have been driven and guided by a fundamental shift in the public sector’s service mindset.

The traditional approach to public service delivery conceived of a single customer profile, with which the government agency interacted according to a clearly defined set of rules and accountabilities. In this “one-size-fits-all” model, any special needs were handled as exceptions to the standardised “fair treatment” provided as the norm. As public agencies embraced customer service values, they began to offer customised and even personalised services to differentiated groups of customers within their purview.

However, the fundamental truth of public interaction with the Government is that often, many agencies are involved even in basic activities such as buying a new house or starting a new business. Further, customers who use public services do not differentiate between different government agencies—they see and expect the Government to operate as a seamless entity.

There is also time pressure on the Public Service to deliver on the ICT promise of ubiquitous connectivity and service on-demand. One approach is to modularise as many public services as possible, creating Lego blocks out of fundamental units of services, which can be quickly assembled in different combinations on the fly to meet diverse requests on demand.

This implies more than just the need for front-end integration of services. It also calls for the need to better share data among and across agencies—not just to reap immediate service efficiencies and synergies, but also to enhance business intelligence and customer understanding in order to understand the customer base more broadly across the public sector. This is no small feat, as it would require a review of current policies and legislation limiting agencies’ ability to share data, to streamline processes, and leverage common IT systems. More subtly but just as vital is the nurturing of a whole-of-government mindset among public officers not yet accustomed to designing public services and reviewing public policies across different agencies. There needs to be clear recognition, that what the Government can achieve as an integrated whole is much greater than the sum of the individual agencies.

TOWARDS GREATER E-ENGAGEMENT

The Public Service must remain responsive to changing needs, aspirations and circumstances of Singaporeans over time. Although Singapore was ranked as the world’s first in Accenture’s 2007 report on Excellence in Customer Service, the most recent UN eGovernment Survey (released in January 2008) rated Singapore unfavourably due to, amongst other things, poor showing in the e-participation index of our citizens in public policy discussions and formulation process.

In the next generation of e-Government, electronic public services must go beyond the merely transactional. They will also involve electronic means for government to more effectively engage citizens in the formulation of public policies. Singapore has already started on this effort.

e-Government has become the primary interface between the Government and Singapore’s citizens and businesses.

Since 2005, the Reaching Everyone for Active Citizenry @ Home (REACH) website (http://www.reach.gov.sg) has offered a series of online channels including discussion forums, online chats, blogs and emails, in order to gather public feedback as well as facilitate discussion on government policies. Once a year, REACH also organises an eTownhall discussion (using its online chat facility) to allow citizens to have real-time discussions with politicians upon the release of the Budget Speech.

It remains to be seen whether such forms of engagement are sufficient in the eyes of our citizens, as well as international bodies. What is clear, however, is that electronic channels are no longer a niche or alternative means for delivering information and services only when it is convenient or cost-effective to do so. e-Government has become the primary interface between the Government and Singapore’s citizens and businesses. It is a reality that the Public Service has to embrace.

Achievements

GROWING THE NETWORK: ISSUES AND CHALLENGES

Public-Private-People Integration (3Pi) initiatives have provided strong learning opportunities for government agencies venturing into the relatively new frontier of public service delivery through commercial portals. Some of the key challenges that public agencies have had to grapple with include:

Sustainability of the business model:

In a 3Pi project, particularly one that is initiated by the Government, the choice of commercial partner(s) is vital. The chosen partner should have a clearly viable business model or the project will be doomed to failure. Several unsuccessful attempts at 3Pi projects began with the Government providing seed funding to start up the project (usually a portal business). The partner, who more often than not was selected based on technical competence and not business acumen, continued to rely on Government funding to sustain the portal business long beyond rollout. The burden to sustain the commercial portal (especially since the Government’s own portal had ceased operation) outstripped the benefits that had been brought about through the 3Pi approach.

Consumer awareness of government versus commercial content:

While government agencies are free to collaborate with their chosen private sector partner to deliver bundled services, it is necessary to ensure that the consumer can distinguish between government content and commercial content. This is because the Government can only be accountable for its own information and services, and a clear understanding by the consumer of limits and caveats is necessary. This also posts creative and practical limitations on the ways in which Government and commercial can be combined and presented.

Exclusivity:

The Government generally does not grant exclusivity in its engagement with commercial vendors, as it still wants to retain the option of engaging other partners. However, commercial partners frequently prefer to negotiate for an exclusive engagement, as it provides protection against competition and gives a certain assurance of business demand. In fact, some commercial partners view this as a critical success factor for the partnership to flourish.

Despite these challenges, public agencies who have engaged in 3Pi projects have gained valuable insight into business thinking, modelling and marketing. Businesses have also come to appreciate the Government’s need to strike a balance between creative flexibility and public accountability. These experiences continue to reap benefits for public-private sector relations well beyond the scope of the specific project. – Karen Wong

BEYOND SERVICE DELIVERY

As part of the e-Government revolution, public service agencies have embarked on a series of broad initiatives in order to reap efficiency gains from streamlining and integration, and IT-enabled automation.

Consolidating Shared Services: Pooling shared services across different government agencies, such as human resource and finance through the Vital.Org initiative, reaps economies of scale across the public sector, while allowing Ministries to retain a high degree of autonomy in decision making.

End-to-end servicing: The Online Business Licensing System (OBLS) integrates the processes needed to apply a plethora of business licences. However, integration means more than just automating the application process—it means possibly doing away with some licenses or using alternative non-licensing measures to achieve regulatory objectives.

Standardisation and collaboration: A new infrastructure, the Standard Operating Environment (SOEasy), is being built as a standardised ICT operating environment for the entire public sector. It will homogenise, consolidate and aggregate demand of all desktops, messaging, online collaboration tools and network environment across all government agencies, involving some 60,000 users across 73 agencies. The result will be a rich, portable and interactive environment through which all public officers can work and collaborate, regardless of their physical location in the public sector. – Karen Wong

NOTES

- The three masterplans are the e-Government Action Plan (2000–2003), the e-Government Action Plan II (2003–2005) and the iGov2010 (2006–2010). For details. refer to https://www.tech.gov.sg/media/corporate-publications/egov-masterplans

- For details, refer to the NS Portal at http://www.ns.sg

- For details, refer to the OneMotoring Portal at https://onemotoring.lta.gov.sg