Water Management in Singapore

ETHOS Issue 02, Apr 2007

With a territory size of just 700 square kilometres (km2), Singapore is a water-scarce country not because of lack of rainfall (2,400 millimetres/year), but because of the limited amount of land area where rainfall can be stored. One of the main concerns of the Government has been how to provide clean water to its population, which currently consumes about 1.36 billion litres of water per day.

Singapore imports its entitlement of water from the neighbouring Malaysian state of Johore. Under agreements signed in 1961 and 1962, Singapore can transfer water from Johore for a price of less than 1 cent per 1,000 gallons until the years 2011 and 2061 respectively.1,2,3

Long-term security of water is an important consideration for Singapore. As a result, the country has developed plans for enhancing water security and self-sufficiency through increasingly more efficient water management practices, including the formulation and implementation of new water-related policies, and significant capital investments in infrastructure and technology.

One main reason for Singapore's success in managing its water resources is its concurrent emphasis on supply and demand management, including wastewater and stormwater management; institutional effectiveness; and an enabling environment which includes a strong political will, effective legal and regulatory frameworks, and an experienced and motivated workforce.

Singapore's entire water cycle is managed by the Public Utilities Board (PUB), a public sector agency previously responsible for managing potable water, electricity and gas. In 2001, responsibilities for sewerage and drainage were transferred to PUB from the Ministry of the Environment, allowing PUB to develop and implement a holistic policy, including protection and expansion of water sources; catchment, demand, stormwater and wastewater management; desalination; and public education and awareness programmes. At present, PUB also has an in-house Centre for Advanced Water Technology, with about 50 expert staff members who provide it with the necessary research and development support

SUPPLY MANAGEMENT: CATCHMENT, DESALINATION AND RECLAMATION, AND LOSS REDUCTION

Singapore is one of the very few countries that looks at its supply sources in their totality. In addition to importing water from Johor, it has made a determined attempt to protect its water sources in terms of quantity and quality on a long-term basis, expand its available sources,4 use technological developments to increase water availability, improve water quality management, and steadily lower production and management costs.

Over the years, there has been an increasing emphasis on catchment management. Protected and partially protected catchment areas are well demarcated and gazetted,5 and no pollution-causing activities are allowed in such areas. At present, half of the land area of Singapore is considered to be protected and partly protected catchment. This ratio is expected to increase to two-thirds by 2009.

Desalination is becoming an important component for augmenting and diversifying available water sources. In late 2005, the Tuas Desalination Plant, the first municipal-scale seawater desalination plant, was opened at a cost of S$200 million. Designed and constructed by a local water company, it is the first designed, built, owned and operated desalination plant in Singapore. The process used is reverse osmosis and it has a capacity of 30 million gallons per day (mgd). The cost of the desalinated water during its first year of operation was S$0.78/cubic metres (m3).6

Faced with the strategic issue of water security, Singapore considered the possibility of recycling wastewater (or used water) as early as the 1970s. It opted for proper treatment of its effluents instead of discharging them to the sea.7 However, the first experimental recycling plant was closed in 1975 because it proved to be uneconomical and unreliable — the technology was simply not available three decades ago to make such a plant practical.

In 1998, PUB and the Ministry of the Environment formulated a reclamation study. Reclaimed water from a prototype plant, started in 2000, was monitored regularly over a period of two years. An expert panel endorsed the safety and potability of the NEWater, a term now used for the treated used water. In 2002, the expert panel confirmed that NEWater was safe and could be used as a sustainable source of water supply for Singapore. Its quality meets the water quality standards of the Environmental Protection Agency of the United States and the World Health Organisation.8

PUB decided to collect, treat and reuse used water on an extensive scale, a step that very few countries have taken. Singapore is 100% sewered to collect all used water. It has constructed separate drainage and sewerage systems to facilitate used water reuse on an extensive scale. From 2002 to 2004, the amount of treated wastewater increased from 1.315 to 1.369 million cubic metres (mcm)/day.9

Used water is reclaimed after secondary treatment by means of advanced dual-membrane and ultraviolet technologies. While NEWater is safe to drink quality-wise, it is also used for industrial and commercial purposes. Since its purity is higher than tap water, it is ideal for certain types of industrial manufacturing processes, such as semiconductors which require ultra pure water. It is also economical for such plants to use NEWater since no additional treatment is necessary to improve its quality. The first year tender price for NEWater from Singapore's Ulu Pandan plant was S$0.30/m3, which is significantly less than the cost of desalinated water. The selling price of NEWater is S$1.15/m3, which covers production, transmission and distribution costs.

Because the production cost of NEWater is less than that of desalinated water, future water demands will be met with more NEWater rather than with the construction of desalination plants. With more industries using NEWater, water saved can be used for domestic purposes.

A small amount of NEWater (2 mgd in 2002 and 5 mgd in 2005, or about 1% of the daily consumption of the country) is blended with raw water in the reservoirs, which is then treated for domestic use. It is expected that by 2011, Singapore will produce 65 mgd of NEWater annually, 10 mgd (2.5% of water consumption) for indirect domestic use,10 meeting 15% of Singapore's water needs.11

The supply of water has been further expanded by reducing unaccounted for water (UFW), which is defined as actual water loss due to leaks, and apparent water losses arising from meter inaccuracies. Unlike other South and Southeast Asian countries, Singapore simply does not have any illegal connections to its water supply systems.

Only 4.5% of water in Singapore is unaccounted for — this is a level that no other country at present can match.

In 1990, UFW was 9.5% of the total water production.12 Even at that level, it would have been considered to be one of the best examples in the world at the present time. By 2006, PUB had managed to lower UFW to 4.5%. This is a level that no other country can match at present. By comparison, in England and Wales, the only region in the world which has privatised its water more than a decade ago, the best level any of its private sector companies have managed to achieve is more than twice that of Singapore's. Similarly, UFW in most Asian urban centres now range between 40% and 60%.

DEMAND MANAGEMENT

Concurrent to the diversification and expansion of water sources, PUB has put in place well-thought out and comprehensive demand management policies. It is useful to review the progress of tariffs for water from 1997 to 2000.

Before 1 July 1997, the first 20 m3/month of domestic consumption for each household was charged at S$0.56/m3. The next block of 20 to 40 m3 was charged at S$0.80/m3. For consumption of more than 40 m3 and for non-domestic consumption, it was S$1.17/m3.

Effective from 1 July 2000, domestic consumption of up to 40 m3/month and non-domestic uses were charged at a uniform rate of S$1.17/m3. For domestic consumption above 40 m3/month, the tariff became S$1.40/m3, which is higher than for non-domestic consumption. The earlier cheaper block rates for the first 40 m3 of domestic consumption was eliminated.

In addition, the Water Conservation Tax (WCT), levied by the Government to reinforce the water conservation message, was 0% for the first 20 m3/month consumption prior to 1 July 1997. For consumption over 20 m3, WCT was set at 15%. Non-domestic users paid a WCT levy of 20%.

Effective 1 July 2000, WCT was increased to 30% of the tariff for the first 40 m3 for domestic consumers and all consumption for non-domestic consumers. However, domestic consumers pay 45% WCT when their water consumption exceeds 40 m3/month. In other words, there is now a financial disincentive for higher water consumption by households.

Similarly, the Water-Borne Fee (WBF), a statutory charge prescribed to offset the cost of treating used water and for the maintenance and extension of the public sewerage system, was S$0.10/m3 for all domestic consumption prior to 1 July 1997. Effective 1 July 2000, WBF was increased to S$0.30/m3 for all domestic consumption.

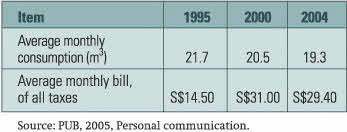

The impact of these tariff increases on consumers can be seen in Table 1:

TABLE 1. AVERAGE MONTHLY CONSUMPTION AND BILLS PER HOUSEHOLD, 1995, 2000 AND 2004

Average monthly household consumption steadily declined from 1995 to 2004. The consumption in 2004 was 11% less than in 1995. During the same period, the average monthly bill more than doubled.

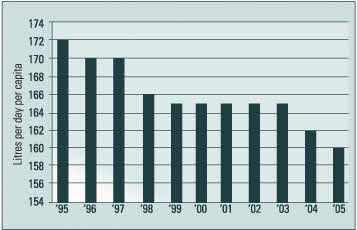

Figure 1 shows the domestic water consumption per capita per day from 1995 to 2005. It shows a steady decline in per capita consumption, from 172 litres per day per capita (lpcd) in 1995 to 160 lpcd in 2005, because of the implementation of demand management practices.

FIGURE 1. DOMESTIC WATER CONSUMPTION, 1995 TO 2005

These statistics indicate that the new tariffs had a notable impact on the behaviour of the consumers, and have turned out to be an effective instrument for demand management. This is a positive development since the annual water demands in Singapore increased steadily, from 403 mcm in 1995 to 454 mcm in 2000. The introduction of demand management policies resulted in the lowering of this demand, which declined to 440 mcm in 2004. Water tariffs have not been raised since July 2000.

In terms of social equity, the Government provides specially targeted help for lower-income families. Households living in one- and two-room flats receive higher rebates during difficult economic times. For hardship cases, affected households are eligible to receive social financial assistance from the Government.

The current tariff structure used by PUB has several distinct advantages, among which are the following:

- Pay-as-you-use: There is no low "lifeline" tariff, used in many countries with the rationale that water should be affordable as a basic necessity. Such a tariff in effect subsidises consumers who can afford to pay for the actual quantity of water they consume. In Singapore, the poor who cannot afford to pay for the current water tariffs receive a targeted subsidy instead. This is much more efficient socio-economically, instead of providing subsidised water to all households irrespective of their economic conditions.

- Disincentive to over-consume: The current domestic tariff of water consumption up to 40m3/month/ household is identical to the non- domestic tariff. In other words, commercial and industrial users do not subsidise domestic users, which is often the case in many other countries. However, households who use more than 40m3 of water per month are subject to higher rates than commercial and industrial rates, as well as more WCT per unit of consumption beyond 40m3/month. These penalties have a perceptible impact on household behaviour in terms of water conservation and overall demand management.

- Differentiated costing: The WBF is used to offset the cost of treating wastewater and for the maintenance and extension of the public sewerage system. For non- domestic consumption, this fee is double that of domestic consumption due to the fact that it is more difficult and expensive to treat non-domestic wastewater.

- Financial viability: Revenue from WCT accrues to the Government. However, a major component of the overall revenue collected through water tariffs accrues to PUB for operation, maintenance costs and new investments. This is in sharp contrast to many countries where internal cash generation of water utilities to finance water supply and sanitation has steadily declined.

OVERALL GOVERNANCE

An institution can only be as efficient as its management and the staff that work for it, and the overall social, political and legal environment within which it operates. Water management in a country can only be efficient if its holistic management of other development sectors — be they agriculture, energy or industry — is just as effective. The current implicit global assumption that water management can be improved unilaterally when other sectors remain inefficient is simply not realistic.

The overall governance of the water supply and wastewater management systems in Singapore is exemplary in terms of its performance, transparency and accountability.

Human Resources

Most water utilities in Asia have a limited say over their own staff recruitment and remuneration — often owing to political interference, union activity or lack of administrative mandate. Corruption is also endemic in many places. As a result, these utilities are beset by problems such as lack of competence, inability to recruit qualified staff, or overstaffing. This results in inefficiency and low productivity.

PUB offers a competitive remuneration and benefits package benchmarked to market rates, provides strong performance incentives and pro-family policies, and is committed to train its staff for their professional and personal development. As a result, it has managed to attract and retain good performers and ensure good organisational performance. With a good remuneration package and a strong national and organisational anti-corruption culture, corruption is also not an issue in PUB.

Capital Investment

The Singapore experience indicates that given autonomy and other appropriate enabling environmental conditions, the utilities are able to be not only financially viable but also perform their tasks efficiently. Such an approach has enabled PUB to fund its new capex investments over the years from its own income and internal reserves. In 2005, for the first time, PUB tapped the commercial market for a S$400-million bond issue. The budgeted capex for the year 2005 was nearly S$200 million.

Outsourcing

Unlike many other similar Asian utilities, the PUB has extensively used the private sector where it did not have special competence or competitive advantage in order to strive for the lowest cost alternative. Earlier, the use of the private sector for desalination and wastewater reclamation was noted. In addition, specific activities are often outsourced to private sector companies. According to the Asian Development Bank (November 2005),13 some S$2.7 billion of water-related activities were outsourced over the "last four years", and another S$900 million will be outsourced during "the next two years" to improve water services.

Overall Performance

No matter which performance indicators are used, PUB invariably ranks in the top 5% of all urban water utilities of the world in terms of its performance. A few of these indicators include:

- 100% of population has access to drinking water and sanitation;

- 100% metering of the entire supply system, from water works to consumers;

- unaccounted for water as a percentage of total production was 4.5% in 2006; and

- monthly bill collection efficiency was 99% in 2004.

CONCLUSION

Viewed from any perspective, any objective analysis has to conclude that water supply and wastewater management practices in Singapore have been exemplary in recent years. Its water demand management practices are unquestionably one of the best, if not the best, whether among the developed or developing countries, irrespective of whether a public or private sector institution is managing the water services. Singapore has successfully managed to find the right balance between:

- water quantity and water quality considerations;

- water supply and water demand management;

- public sector and private sector participation;

- efficiency and equity considerations;

- strategic national interest and economic efficiency; and

- strengthening internal capacities and reliance on external sources.

In other words, the country has successfully implemented what most water professionals have been preaching in recent years.

By ensuring efficient use of its limited water resources through economic instruments, adopting the latest technological development to produce "new" sources of water, enhancing storage capacities by proper catchment management, practising water conservation measures, and ensuring concurrent consideration of social, economic and environmental factors, Singapore has reached a level of holistic water management that other urban centres will do well to emulate.

This article was adapted with permission from the paper "Water Management in Singapore", first published in the International Journal of Water Resources Development, Volume 22, No. 2, June 2006: pp 227-240. © Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, www.tandf.co.uk/journals .

NOTES

- Lee, M. F. and Nazarudeen, H. "Collection of urban storm water for potable water supply in Singapore." Water Quality International, May/June (1996): 36-40.

- Appan, A. "A total approach to water quality management in partly-protected catchments." (paper presented at The Singapore Experience, International Workshop on Management and Conservation of Urban Lakes, Hyderabad, India, June 16-18, 2003).

- Lee, Poh Onn, "Water management issues in Singapore." (paper presented at Water in Mainland Southeast Asia, Siem Reap, Cambodia, November 29 – December 2, 2005).

- Trade Effluents Regulations (1976) Water Pollution Control and Drainage Act, Act 29/75, Pub. No. SLS 29/76, Republic of Singapore.

- Public Utilities Board, Annual Report 2002, (Singapore: PUB, 2002).

- Ministry of the Environment and Water Resources, Key Environmental Statistics 2005, (Singapore: MEWR, 2006).

- Public Utilities Board, Annual Report 2003, (Singapore: PUB, 2003).

- Khoo, Teng Chye, "Water Resources Management in Singapore." (paper presented at the Second Asian Water Forum, Bali, Indonesia, August 29 – September 3, 2005).