Ageing Population: What to Expect and What to Do

ETHOS Issue 01, Oct 2006

What are the ramifications of a demographic shift towards an ageing population? When post–World War II baby boomers enter their retirement phase, the supply of labour will fall. In Germany, as in many other European countries, the population in the working age of 15 to 64 years is likely to shrink by around 20% between 2005 and 2050. This will put Germany’s growth potential under pressure. If no action is taken, Germany’s trend growth rate is set to be cut in half in the longer term from its current level of 1.5%. The working age population in Singapore is likely to decline by 16% by 2050, reducing the share of 15- to 64-year-olds from 72% to 56%. All other things being equal, this would lower Singapore’s growth potential by half a percentage point.

In addition, the quality of the labour supply could decline. Technical expertise is largely generated by young workers; productivity and innovation potential is likely to fall in ageing societies. Older workers are also usually less flexible and mobile than their younger counterparts. This restricted mobility of the labour force will in future slow down the formation of clusters of specialisation and structural change, since it is mainly younger workers who smooth the implementation of new product, process and management ideas. We must also expect less willingness to assume risk and a decline in the number of start-ups. In many countries, 25-to-45-year-olds are among the most active in setting up their own businesses.

How can we tackle the challenges of this demographic shift? In principle, lift the participation rate first; second, increase work life and third, raise net immigration. However, each of these measures can at best only dampen the negative demographic effects.

STRETCHING THE WORKFORCE AND WORKING HOURS

Policy makers have to focus on raising the participation rates of women and older people. In Germany, only 24.3% of 60-to-64-year-olds are still gainfully employed. The Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) average is 38.5%, while the figure in the US is 49%. If Germany’s participation rate of the 55- to 64-year-olds matched the OECD average of 51.8%, the size of the workforce could increase by 2.25% or 800,000. The instruments to achieve a higher participation rate of the “young” seniors are manifold. Among them, the most important are to correct the inducement of early retirement, reduce the period of entitlement to unemployment benefits, and eliminate high severance payments, extensive job dismissal protection as well as seniority principles.

Europeans should start working at an earlier age and retire later. In the public sector in particular, early retirement is granted much too often and at subsidised conditions, especially in Italy, France and Germany. Singapore has extended its prescribed minimum retirement age from 60 to 62 years; efforts to recognise the contribution and significance of older workers are steps in the right direction.

In addition, the participation rate for women must be raised by implementing new child-minding arrangements and more creative working time models and speeding up organisational reforms. This is an area in which both Germany and Singapore can further improve.

An ageing population will change the structure of the economy, principally to the benefit of the healthcare sector.

Average weekly and/or annual working times could also be increased. Fewer workers have to work more hours in order to compensate for the negative demographic effect on potential growth. This implies, among other things, a higher share of women in the workforce or greater numbers in part-time jobs switching over to full-time positions. This also requires an increase in collectively agreed weekly working times.

MIGRATION WILL HELP, BUT WILL NOT REVERSE THE SHIFT

Economies with a shrinking and ageing population obviously need selective migration and thus a sensible immigration policy. Immigration cannot reverse the unfavourable demographic shift – at least not within reasonable, socially acceptable parameters. To illustrate this: all else being equal, Germany will need net immigration of over 500,000 persons every year to stabilise the labour force at its present size.

Immigration can, however, help to slow down the process of ageing and shrinking of the population and mitigate its negative economic consequences. The younger, more flexible and better qualified the immigrants, the more favourable the outcome would be. In traditional pro-immigration countries, it is normal for immigration to be regulated accordingly. EU states could adopt some of these standards.

Migration policy should not stop at identifying suitable immigrants, but should also help them integrate well into society. It is of great importance for the host countries to promote harmonious race relations. Singapore is fortunate in this regard as it naturally understands the complexities of a multi-racial nation.

POPULATION TRENDS: LOOKING AHEAD

The development of the population over the next decade could make us imagine that all is well. Population numbers in Western Europe are expected to increase until 2020, but will then decline dramatically. Between 2020 und 2050, they will shrink by almost 16.5 million or 3.5%, according to UN projections. According to the UN, Singapore’s population is also set to shrink by 2% or by some 108,000 persons between 2035 and 2050. However, it will still be almost 900,000 more people in 2050 than today. Other countries in Asia will face the same problem but with different starting points. Asia’s population as a whole will continue to increase well into 2050, thanks to the growing populations in most Asian countries, most notably India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Bangladesh.

BIRTH RATE LAGGING BEHIND REPLACEMENT RATE

The reason for the decline in Europe’s population is that the birth rate is much lower than the replacement rate and even the steady rise in life expectancy cannot offset its impact. Germany is at the lower end of the European Union (EU) scale with 1.4 children per woman. For nearly 30 years, only two-thirds of the parent generation has been replaced. The Federal Statistical Office population projections for Germany are based on a constant birth rate of 1.4 children per woman between now and 2050. Singapore’s current birth rate, at 1.24, is at similar levels.

LIFE EXPECTANCY TO INCREASE

Life expectancy in Europe will rise by around three years by 2020 and seven years by 2050. In Asia, coming from a lower base, life expectancy will rise by some four years by 2020 and 10 years by 2050. Global life expectancy has risen in almost linear fashion by 2.5 years per decade during the last 160 years. In Germany, life expectancy has increased by no less than 30 years in the last 100 years. In the past, life expectancy has been systematically underestimated. Demographic experts are discussing whether there is actually a limit to life expectancy. Some argue there is none.

The confluence of a low birth rate and the rising life expectancy will cause the median age in Germany to increase considerably: by 2050 half of the population will be over the age of 47.4 years against 42.1 years in 2005. Singapore’s median age is expected to increase by 14.6 years to 52.1 years in 2050. It will almost match Japan where the median age will rise by almost 9.5 years to 52.3 years. By contrast, the population of the US will be among the most youthful of the industrial nations in 2050. The median age there will rise by 5 years to 41. – Norbert Walter

MAKING UP FOR A DECREASE IN QUANTITY BY AN INCREASE IN QUALITY

The economic success of a country, and the creativity and productivity of its citizens are only partly a question of population size and age. More important are their knowledge and skills as well as their work ethic.

Europe has to reform its education system. The decisive step will be to shorten the duration of school education and to increase competition between educational institutions. Universities should be granted autonomy in matters of personnel and fees. The high spending on education in the US is the reason why a relatively large share of the population (38%) has completed higher education. Germany can by comparison only boast a share of 24%, matching the OECD average. In Singapore, around 20% of the population has completed university, a level which is still below the OECD average. However, Singapore is increasingly looking to adapt American models of education for its own system in order to increase its attractiveness in the global education market, and to raise the numbers of foreign students from 60,000 in 2003 to 150,000 in 2012.

LIFELONG LEARNING, MOBILITY AND FLEXIBILITY

Yet school education will no longer suffice as the vocational preparation for one’s whole life. Students and workers have to understand that their education and training are their most important investment in life – much bigger than a car or a flat – which will keep them employable in an ever faster changing environment. In this respect, Europe can learn a lot from Asia. Lifelong learning is no longer a choice but a must for workers of the future. However, the onus is not only on workers; management principles and systems have to change too.

POPULATION TRENDS WORLDWIDE

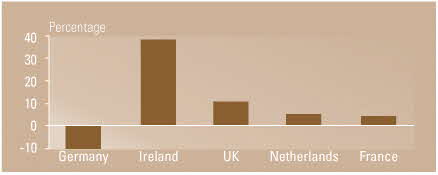

Demographic developments will vary across Europe in the coming decades: while the population will decline in many countries, such as Germany, it will rise in France, Ireland, the Netherlands and the UK.

POPULATION CHANGE BY 2050 (EUROPE)

Asia’s population will continue to increase well into 2050. Yet some countries will face a declining population:

Labour markets in Europe need to be made more flexible. The principal goal is to improve the incentive for firms to hire new workers, by pursuing a moderate wage policy geared towards the needs of labour market adjustments and towards the abolition of excessive protective provisions that stymie job creation. Greater tolerance for risk-taking is required, with regard to matters such as dismissal protection and starting up a company. Greater mobility is also needed, for example, a greater willingness to relocate or change jobs.

In particular, the work ethic has to be boosted, in terms of work intensity, working hours and learning time. Motivation to do a good job must be remunerated in pecuniary and non-pecuniary ways.

IMPLICATION ON ECONOMIC SECTORS

An ageing population will change the structure of the economy, principally to the benefit of the healthcare sector. Other business lines that stand to gain are asset management, pharmaceuticals, bio-technology, medical technology, support and social services. Niche products and services for an older population will be in demand.

Products and services bought primarily by young people and families, including toys, family vacations and single-family homes, will have less growth potential. Manufacturers of internationally tradable goods can partially compensate for this by increasing their exports to more populous and younger regions. Suppliers of products and services provided directly to the local customer, such as retailing and real estate, will be hardest hit by population decline.

PENSION SCHEMES: RETHINKING PRIORITIES

Pension and healthcare systems are probably the most intensively discussed consequence of population trends. For the past 30 years, old-age provision has been insufficient in Europe. For an entire generation, we have failed to set aside reserves for the future one way or the other. Instead, with the pay-as-you-go system, we have put an ever-increasing burden on present and future working generations.

The ageing of society will put pay-as-you-go systems under catastrophic pressure: contributions are falling with the decreasing number of contributors, while paid-out benefits will rise sharply as a result of the increasing number of pensioners and the extension of pension periods. Efforts to correct imbalances by raising contribution rates or broadening the tax base will likely lead to a dead end as they lead to fewer jobs and more emigration.

However, old-age pension systems based more strongly on personal or occupational schemes also face a challenge. In periods of shrinking growth, traditional occupational pensions (defined benefits), especially those based on book reserves, run into the same problems as public pay-as-you-go systems in markets with a domestic orientation. This is because the massive deterioration of old-age dependency ratios also applies to companies.

Occupational and personal pension plans which are based on funded schemes, especially ones diversified with a strong international orientation, could perform better, although it is true that in the last three years, many of these pension systems also had to cope with considerable setbacks due to tumbling stock prices. While the extent of the under-funding of company pension funds is rapidly and almost fully reflected, this does not apply to old-age provision in the public sector and the statutory pension schemes, where transparency is insufficient. Here, a rapid, full-scale correction is required.

Privatisation, public-private partnerships and private initiatives will play a key role in absorbing the pressure on public finances and social systems.

In Singapore’s context, the Central Provident Fund (CPF) is among the most advanced in Asia, yet there are still challenges to overcome. Recent findings suggest that the population’s need to finance housing, for instance, has eaten into their retirement reserves. The CPF, as well as its members, may benefit from a review of its priorities.

FUNDING PENSIONS: THE NEED TO DIVERSIFY

Investment decisions in funded pension systems have to become more intelligent. All pension systems have to take account of the fact that the yields of investments in the next 30 years will be far below the levels of the last 30 years. In my view, half the yield level should be a safe bet, while two-thirds would be the best-case scenario. To count on more would be to exaggerate expectations with regard to pension payments.

In the financial market, calculations show a drop in capital yields until 2035 of about 1.25%, without considering international diversification. Some argue that when the baby boomer generation starts to retire and consume its capital in the coming 15 years (“dissaving”), there is a risk of a falling saving rate and lower yields on financial assets (“asset meltdown hypothesis”). Others disagree and argue that dissaving will happen gradually, investments will be internationally diversified, and those still working will likely increase the level of their private retirement savings. In this regard, government policies may be able to play some role in helping to sway the population to make the right choices.

State pensions in pay-as-you-go systems and returns on domestic investments depend on economic growth at home. Therefore, investing abroad is the only way to decouple retirement incomes, at least in part, from economic development in the home country. One could invest in export-oriented companies. If more capital is to flow into emerging market economies, strategies must be developed to promote risk management and financial stability. Successful financial services providers will probably act increasingly as intermediaries in the next few decades, gathering liquidity in the ageing European countries and passing it on to emerging markets which demonstrate greater political and economic stability.

The future of European government bond business depends primarily on whether the ageing countries manage to reform their social security systems and reduce their debts in time. Governments failing to cut their deficits run the risk being downgraded by rating agencies.

Europe has generally recognised that pay-as-you-go pension systems alone are not a sustainable solution for retirement income and must therefore be supplemented by funded pension systems. Currently, 80% of an average pensioner’s income is state-financed in Germany, compared with 45% in the US and 65% in the UK. Retirement provision, and thus asset management, will profit most from the ageing process in Europe, as the volumes of institutionally managed assets in many Continental European countries such as Germany, Spain and Italy, are considerably smaller than that in the US and Britain.

GLOBAL SHIFTS IN SAVINGS AND INVESTMENT

Population ageing and decline will influence global economic and political power structures as well as international capital flows and exchange rates. Already, there have been endless debates on the current global imbalance and the need for Americans to save more and Asians to spend more. Generally, there is scope for Asians to spend more based on the overall increase in population size between now and 2050, but this will not necessarily apply in countries such as China, South Korea and Singapore, where the domestic population will shrink in a few decades’ time. In the future, savings plans will have to take into account a higher dependency ratio in these countries.

Inter-regional and inter-temporal differences in ageing result in divergent saving and yield effects (“demographic arbitrage”). Over the next few years, saving and capital accumulation will probably focus on the European countries –where baby boomers are in their main saving phase – providing great opportunities for asset managers.

Lending will tend to shift increasingly to the US, Asia and Latin America, where large numbers of young people are expected to be seeking loans and equity capital for business and private purposes. However, the absorption capacity of younger emerging countries could be a limiting factor. Political and economic stability in the emerging markets are essential premises for the stronger inflow of capital. Given this trend, lenders and borrowers will place rising demands on risk management for credit and currency businesses.

There is considerable growth potential in countries where birth rates have fallen only in the last 10 to 20 years or where the population continues to grow. If this demographic window of opportunity is combined with favourable political and economic conditions, the growth potential is high. Countries that fall into this category include those in Asia (India, Indonesia and the Philippines), Latin America (Argentina, Brazil and Mexico), and the US.

Foreign capital investment by European countries in the younger economies of South America and Asia is expected to increase substantially, and also in the Middle East and Northern Africa depending on political and economic developments. OECD calculations suggest that G3 net foreign assets will expand strongly until about 2030, and then fall again via current account deficits of up to 3%of GDP. – Norbert Walter

DEMOGRAPHIC CHANGE AND CORPORATE BEHAVIOUR

The ability of ageing European societies and economies to adapt and adjust is crucial to master the challenges of a demographic decline. The job must not fall solely to the public sector; we must enlist the help of everyone. Privatisation, public-private partnerships and private initiatives will play a key role in absorbing the pressure on public finances and social systems.

Private-sector entities must be made aware of the challenges facing them as the labour pool shrinks. Demand for less qualified staff is likely to continue to fall in the future, making it unrealistic to hope that the problem of unemployment will be solved by demographic change. The competition for highly qualified employees (“war for talents”) is likely to become more intense and inflate salaries for this group.

CONCLUSION

The impact of the demographic shift will be wide-ranging, leading to changes in the way various sectors operate as well as the way individuals live. Appropriate migration policy should help mitigate some of the negative implications in the countries with a shrinking population, but it will not reverse the overall population trend.

In preparation for a smaller pool of labour in the next few decades, more economically-inactive persons need to be enticed to enter the workforce. These include women and the elderly. However, suitable work arrangements for women must be arranged so as not to depress the birth rate further. Furthermore, stretching the working life will be necessary to reduce the burden on the active population. This must be supported by life-long learning and improvements in the health and recreation sectors. The government must raise public awareness of the implications of an ageing society in addition to thoroughly preparing key sectors such as education and healthcare in the coming decades.

Pension schemes will have to enlist the help of all stakeholders. Priorities must be reviewed in order to make sufficient provision for old age. In addition, expectations for investment returns must be realistic. The scope of investment activity will certainly have to be enlarged, which will necessitate an upgrading of risk management and capital market efficiency in emerging markets.