Using Case Studies to Develop Policymaking Competencies in Continuing Education

ETHOS Digital Issue 14, Dec 2025

Introduction

Policymaking is a complex, often iterative process, that involves domain knowledge, sense-making, critical thinking, systems analysis and creative thinking. The competencies needed for effective policymaking are likewise complex,1 and they are best learnt inductively rather than taught.

Case studies have long been used to help policymakers acquire these competencies, by offering a specific real-world context for critical thinking and decision making. Case studies are effective in the development of policymaking competencies because they provide "a focal point around which analysis, experiences, expertise, and observations can be exchanged."2

A good case study presents a range of policy issues set within a story with different interacting variables.3

Learners interact with one another to interpret, analyse, discuss and develop their own solutions to these issues.<p></p>

The Three-Stage Learning Process

The traditional method of using case studies involves a three-stage learning process that requires individual preparation, small group discussion and large group discussion:4

Learners familiarise themselves with the case study contents before the start of the programme.

Learners discuss the case study in small groups to "check insights; assumptions and preparation against those of others; clarify understanding; listen attentively and critically to others; and argue for positions based on convictions developed during the individual preparation stage."5 Both individual preparation and small group discussions take place outside of curriculum time.

This is the finale where learners gather in a single large group, in class, to engage in deep discussions centred on the case study, pushing learning beyond what could be achieved individually and in small groups.

Using Case Studies in Public Policy Programmes

Case studies are also used outside academic settings to development policymaking competencies in continuing education and training. For instance, they are used at the Civil Service College Singapore in two foundation-level policy programmes: the Policy in Practice (PIP) Programme and the Foundation Policy Programme: Thinking and Writing Clearly (FPP).

Learners from the PIP and FPP programmes comprised Singaporean policy officers with one to two years of policy work experience. They were nominated to attend the programmes to improve policymaking competencies required in their job roles. A challenge for those relatively new to policymaking is the lack of work experience, policy experience and exposure to the inner workings of government. To plug this gap, these foundational policy programmes were designed for learners to participate in deep learning where they would apply models and complete tasks, and in the process discover insights about policy practice.

From January 2023 to June 2024, there were a total of 19 PIP and FPP programmes with 774 learners from more than 60 public agencies across the Singapore Public Service. These programmes were conducted by four instructors who could choose two out of a selection of five case studies for their programmes. The case studies used in the programmes typically comprised 10-page structured cases that described policy issues and challenges.

To better understand the impact and efficacy of using case studies to develop policymaking competencies in the context of these foundational policy programmes, data from three sources were analysed: programme evaluation questionnaires of learners who attended the programmes, in-depth interviews with instructors who used case studies for discussions in the PIP and FPP programmes, and in-class observation of the case study discussions.

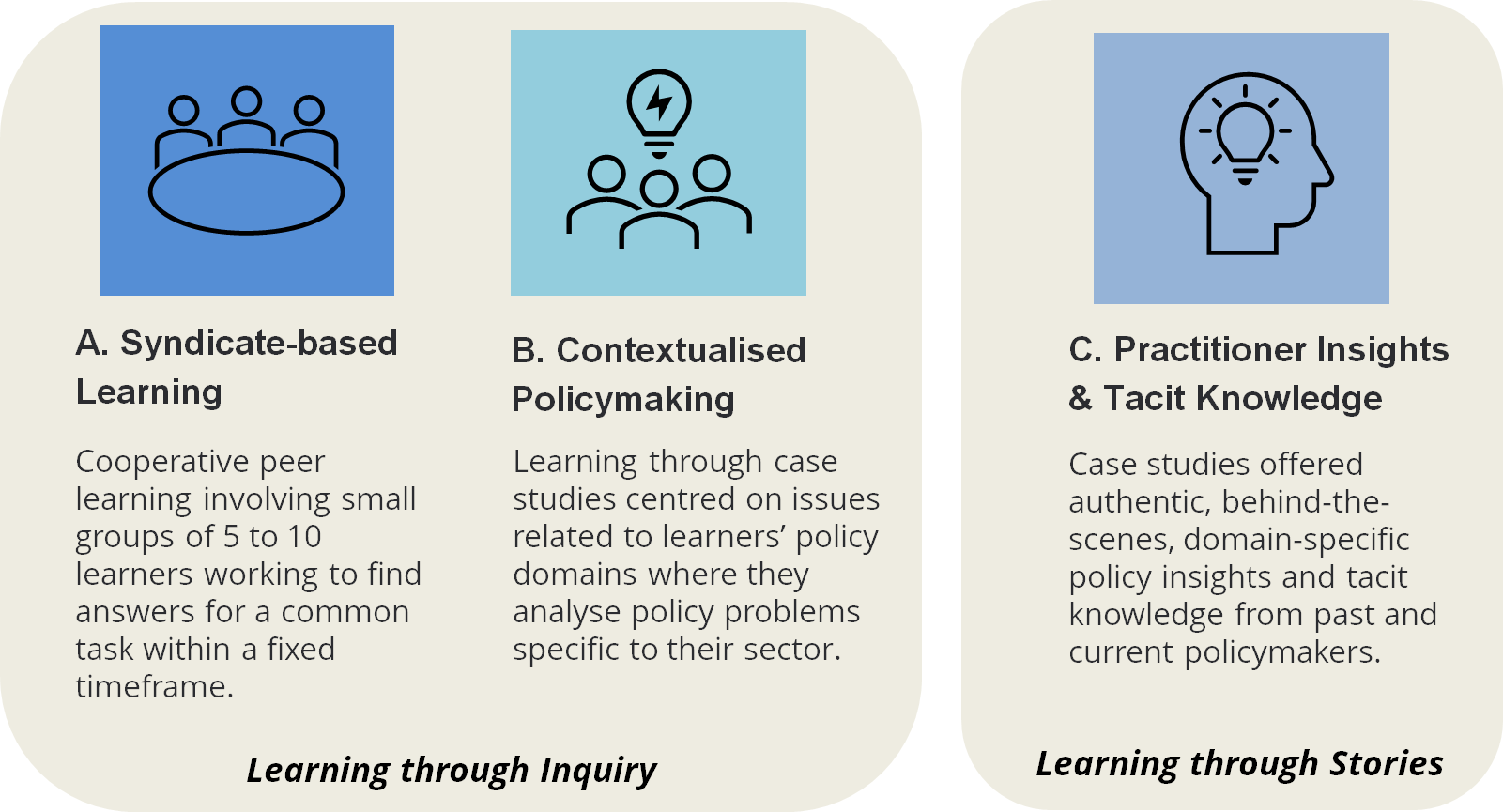

Findings from this analysis yield three distinctive thematic features of learning in this context: Syndicate-based Learning, Contextualised Policymaking and Practitioner Insights and Tacit Knowledge.

Syndicate-based Learning

Syndicate-based learning — cooperative peer learning involving small groups of 5 and 10 learners working to find answers for a common task within a fixed timeframe — was more suitable for the adult learners of the PIP and FPP.

Unlike the traditional three-step case method, the syndicate learning approach features individual preparation and small group discussion conducted in class rather than before class. Large group discussion in a single conversation is also replaced by groups giving presentations on assigned questions, relating to specific elements of each case study.

Although PIP/FPP learners were given the case studies for pre-reading at least two weeks before the start of the programme, most did not spend much time on the materials. Unlike academic students, these early career officers with busy work schedules could not devote time to read the pre-programme materials, much less to form small groups to discuss them, before class.

Many of us have our Business-As-Usual work to do and would only glance through the pre-course materials.

This is where I think adult learning is very different. Most of the learners would say 'No time, because I've got so much work to do.' They are busy. There is no protected time for them to read. They were taking work time to carry out learning activities required by the programme. Then there were other reasons — 'I also have family things to do.' Most feel that 'I have work pressure, I have family pressure. So, I skim through the case study. I don't really have a good sense of the case study, or I haven't read it."

Since the adult learners were often less prepared when entering a case study discussion, instructors unanimously used a syndicate learning approach. This helped level up learners who might not have read or analysed the case study, allowing them to do so during in-class small group discussions instead.

Contextualised Policymaking

Using questioning techniques that centred on 'how', 'what' and 'why',6 instructors probed learners to analyse the information provided in the case study to identify policy issues, apply policy frameworks, present their policy ideas and solve policy problems — reflecting the competencies required of policymakers.

PIP/FPP adult learners were observed to be highly articulate and could present their ideas clearly and convincingly to a high extent. However, while learners were effective in analysing policy issues and presenting well thought-through issues based on the information provided in the case study, they had limited knowledge of their own policy domains, other policy domains and the inter-dependencies within the larger system.

Learners' analyses were limited by their own policy and work experiences, which were at the early stages of their career. They could apply critical thinking based on what could be gleaned from the case study but could not further deepen discussions.

Some learners provided feedback that they would prefer case studies situated in their own policy domains so that they could better analyse policy problems within the context of their work.

It is hard to formulate policy analysis for content areas we are not familiar with, and within such a short period of time.

The quality of discussion depended a lot on group members' contribution.

For this group of younger policymakers, we need to have a case study that is situated in their domain because ultimately, they are making policies within their domains. This is very different from if you are using a case study in say, a leadership programme where you can use a case study from any domain to learn leadership lessons. In a policy programme, it is about the practice of policymaking within a very specific domain. I need to keep coming back to ask them how is this relevant to them in their current job role, in their current context.

Nevertheless, adult learners were hungry for knowledge about how to navigate the operating environment within their policy domains (e.g., social, economics, health and education).

Practitioner Insights and Tacit Knowledge

Learners were keen to discover authentic, behind-the-scenes, domain-specific policy insights and tacit knowledge from past and current policymakers. They wanted to know how experienced and veteran policymakers identified root causes of policy issues, made decisions about trade-offs, and dealt with policymaking dilemmas.

Such practitioner insights also conveyed policy fundamentals, policy principles, policy vision, and a sense of operating context in ways that helped young policymakers develop sensibilities, ethos and evaluative judgement in policymaking.

In terms of storytelling, it is really powerful. It's not just about skills. It is powerful at imparting knowledge. 'Oh, is this what happened?' 'Is this how government works together?' 'I didn't know this back-story?' Learners find this interesting, but it may not directly lead to them acquiring policymaking skills. It is beyond inductive learning. It inspires ethos, a sense of belonging, which is very powerful.

The case studies were really interesting and enlightening, so more sample case studies (as optional reading, maybe).

Learners considered conciseness and format as important as the substance of the content itself. A consistent theme was to use shorter structured stories in learning. Learners were drawn to more concise case studies with some degree of interaction.

Length has become something of a concern. Patience for case studies is very thin. The length is something that people don't have patience for anymore. They are not doing a degree programme, and they don't have patience for a long case study. Case studies have evolved. They don't have to be written down. They can be videos, podcasts, etc.

These three themes are connected by two instructional strategies — learning through inquiry and learning through practitioner stories. The former lets policymakers develop critical thinking skills, while the latter develops policy domain knowledge and policy sensibilities. Both are essential competencies for policymakers to integrate policy theories with practitioner experience.

Conclusion

In conclusion, learning with case studies is useful and relevant to the development of policymaking competencies but they serve different functions. First, policy domain knowledge is integral to policymaking, alongside other policy skills such as critical thinking, sense-making, communications, systems thinking and creative thinking skills. The tacit and practical knowledge of policy veterans offer insights on how these various skills and knowledge are combined. Second, learning with case studies serve a dual function in the development of foundational policymaking competencies - they are used for inquiry-based learning and story-based learning.

For adult learners in continuing education programmes such as PIP and FFP, learning with case studies for policymaking is more effective if case studies are situated in the learners' policy domains. Policy is not developed in a vacuum — it is situated within specific operating contexts with social, political and economic stimuli. An understanding of the context in which policy is made is part of policymaking and a much-needed competency.7

In foundational policy programmes where learners could benefit from deeper learning from the knowledge and experience of veteran policymakers, curating and designing a variety of case studies in different modalities could help meet different learning needs, as well as offer a wider array of learning experiences. Programme design could vary to include a combination of teaching cases for facilitated inquiry-based learning and story-based cases for self-directed learning.

Learning with cases is effective only if there are purposefully designed and well-crafted narratives, as well as engaged learners. The way the case study narrative is structured, sequenced, presented and distributed could be vastly different depending on how it is used. A case study intended for facilitated learning in a classroom setting may differ in writing and design from one intended for self-directed, self-paced learning by adult learners. There is scope for further research on how to design a good case study to achieve different learning goals that are useful to adult learners in developing policymaking competencies.

NOTES

- A report on Competencies for Policymaking identified 36 competencies for innovative policymaking organised into seven clusters: Advise the Political Level, Innovate, Work with Evidence, Be Futures Literate, Engage with Citizens and Stakeholders, Collaborate and Communicate. See: Schwendinger, F., Topp, L., & Kovacs, V. (2022). Competencies for policymaking — Competence frameworks for policymakers and researchers working on public policy, EUR 31115 EN, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

- Harling, K. F., & Akridge, J. (1998). Using the case method of teaching. Agribusiness, 14(1), 1-14.

- Barnes, L.B., Christensen, C. R. & Hansen, A. J. (1994). Teaching and the case method. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business School Press.

- Wood, J.D.M., Leenders, M., Maufette-Leenders, L. A., & Erskine, J. (2023). Teaching with Cases (4th ed.). Ontario, Canada: Leenders and Associates.

- Maufette-Leenders, M., Erskine, J. A., Leenders, M. R (2001). Learning with Cases. Ontario, Canada: Ivey Publishing, p. 20.

- These questions correspond with levels 2 to 5 of the Bloom's Taxonomy. See: Bloom, B. S., Engelhart, M. D., Furst, E. J., Hill, W. H, & Krathwohl, D. R. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives: The classification of educational goals. Vol. Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. New York: David McKay Company.

- This echoes the research by Collins, Green and Hunter which emphasised the importance of linking policy context with policy process to strengthen policy analysis. See: Collins, Charles, Green, Andrew, Hunter, David. (1999). Health sector reform and the interpretation of policy context. Health Policy. 47 (1), 69-83.