Rethinking Hybrid Work Design: Insights from Ethnography

Digital Issue 11, Oct 2023

There is broad acceptance that some form of hybrid work will continue after the pandemic.1 Anticipating this trend, CSC’s Institute of Leadership and Organisation Development (ILOD) developed A Leader’s Playbook to Hybrid Work in May 2022 to help public service agencies come to terms with this new form of working and update our ways of working.2 More recent research by experts studying work-from-home (WFH) arrangements have since validated this approach.3

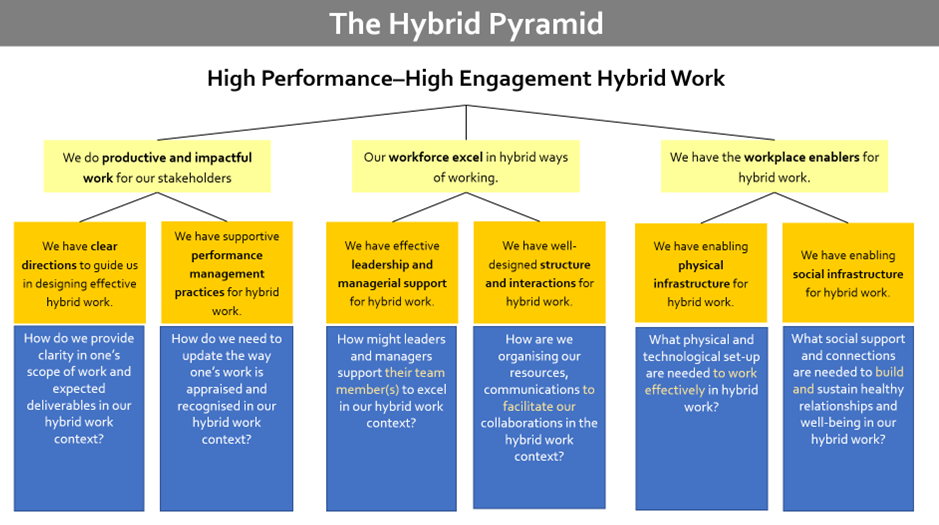

The Hybrid Pyramid, which is part of ILOD’s Playbook, is a systemic framework highlighting key dimensions of work practices for effective hybrid work. We developed the framework with the Public Service context in mind, based on research and ground feedback from the senior management team and staff of a pilot Ministry.

However, despite three years of pandemic-induced working from home and hybrid working arrangements, there seems to be little consensus (and in fact there may be conflicting evidence) on whether these work models are more productive and effective than conventional office-based modes.

| More Office, Less Work from Home | More Work from Home, Less Office |

|---|---|

|

A recent global survey of working arrangements observed that employers generally want more office time.4 The benefits of working in an office, as cited by employees, include socialising and collaborating in person with co-workers. |

The same global survey found that employees want to work from home more often than currently allowed.7 Employees cited WFH benefits such as savings in commuting time and flexibility in managing work-life balance. |

|

Some studies cited in the Economist have claimed negative effects from WFH, such as reductions in productivity and isolation from professional networks.5 A study in India citing an 18% drop in productivity for those working at home, and another study citing a 19% drop for those working at home for a big Asian IT firm. |

A 6-month experiment in a firm—with coders, marketing, finance, and business employees, both recent graduate hires and more senior managers—found that the impact on individual productivity was zero or marginally positive, depending on the metric used.8 Performance evaluations and promotions showed no impact, while lines-of-code written, and self-assessed productivity increased about 4%. |

|

A Stanford study found genuine differences of opinion between employees and managers about the impact of working from home on productivity in 2022 and obtained average effects equal to +7.4% among workers and -3.5% among managers.6 |

Several studies of self-assessment by hybrid workers from different countries have found positive results of an increase of 3% to 5% in productivity.9 |

The issue of hybrid work and its impact on ways of working is bound up with longstanding, implicit assumptions about how work is carried out.

Seeking a fresh perspective, ILOD Principal Consultant Eileen Wong spoke with Thijs Willems, an organisational ethnographer and Research Fellow at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, to explore how an ethnographic lens might shed light on and help reframe today’s shifting work cultures.

The Ethnography of Hybrid Work Culture: A Conversation

Eileen: What is an organisational ethnographic approach?

Thijs: Ethnography is a systematic methodology used to study and describe different cultures. A specific way of looking at the world, it was initially developed and primarily used in the domain of anthropology—the study of human societies, cultures and behaviours. Anthropologists found that the most effective method to intimately understand unfamiliar cultures and societies was to literally live among the people they were seeking to learn about. Organisational ethnography is built on the same idea, but it looks at work settings and other sites that one is usually more familiar with. It can be quite useful to think about work settings through an anthropological lens. This is because becoming a member of an organisation entails learning the lingo and habits of its people, and how they use concepts in contextually specific ways. We can also understand organisations by treating different departments as different cultural ‘tribes’, e.g., the day-to-day tussles between an innovation department and an audit department. Ethnography relies primarily on participant-observation: seeing how individuals actually go about their day-to-day business in a particular context. In practice, participant-observation is the art of “hanging out”: learning to become a part of the culture you are studying so you can describe things from an inside perspective.

Eileen: How can ethnography tell us more about organisational culture than other available research methods?

Thijs: Rather than taking surveys or studying people from concepts the researcher is familiar with (which are inherently ‘biased’ because they are created from the culture one is familiar with rather than based on local ground knowledge), ethnography is based on observing how people actually live and work. This helps them to understand and describe things from the inside out, rather than from the outside in as most research methods would approach their subjects.

Applied to the workplace, this means understanding how people organise their work and their tasks themselves and why they organise it in such a way. Ethnography, unlike many other research methodologies, is particularly concerned with the actual practices of people. If you want to know what administrative work entails, for instance, you must talk to the administrative workers. This often means venturing out into what may feel counter-intuitive.

For example, if you want to study innovation in a specific organisation, the most conventional way might be to read an organisation’s mission statement, their guidelines and espoused values, and talk to the Chief Innovation Officer or some other high-ranked managers. But ethnographers would not stop there. They would try to see how innovation can also be seen as a more bottom-up process. They might hang out at the photocopiers and watercoolers where most informal interaction happens.10

Or they would focus on the interactions between people in ‘corridor-talk’ or when they meet outside the office for a coffee or other beverage. Ethnography is about looking at cultural phenomena not just from one perspective but taking different environments into account.

Too often, we look at work in a much too abstract way. Of course, managers have to do this because that is what managing is about: they handle many pieces of a complex puzzle in order to manage a bigger picture. But this also requires them to often have to gloss over important details. But if we take the approach of considering workers as the experts in how they actually do work, we can better recognise small but significant details.

Counter-intuitive Insights

In one of the Future of Work projects at the Lee Kuan Yew Centre for Innovative Cities at SUTD, we did an ethnographic study with technicians and engineers in the Energy & Chemical industry. Specifically, we wanted to know what expertise is in this work environment, thinking that it would be a good proxy to understand digitalisation of the industry. When we asked technicians how they know what they know, and how they assess the state of a chemical process, they would often shrug the question away claiming that we should ask the decision-makers instead. But we kept digging, and technicians came up with really interesting explanations. For example, they would claim they could "smell" the problem by just being there. Or by “simply knocking on the pipes” they would know “exactly what is going on”. Understanding this became one of the main motivations for the rest of our study, especially because it stands in stark contrast to uber-rational accounts of digital technology that often assume that everything can be captured in data, and that messy, intuitive processes—such as smelling or knocking the pipes—can be automated. It gave us tremendous alternative insights into how we should think about the future of work.Note

- K. W. Poon, T. Willems, and W. S. Y. Liu, “The Future of Expertise: From Stepwise Domain Upskilling to Multifaceted Mastery”, in International Handbook on Education Development in Asia-Pacific, eds W. O. Lee, P. Brown, A. L. Goodwin, and A. Green (Singapore: Springer, 2023), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-2327-1_42-1.

Eileen: How can ethnography help us design better working cultures, including for hybrid work?

Thijs: The clearest way would be to apply it so organisations can go beyond the pure design perspective on how hybrid ways of working must be organised. Often, design is done in a top-down matter. It takes a helicopter view—or a ‘snapshot’—of the organisation and makes decisions based on that. And these decisions can often lead to disappointing results: new spaces are rarely used, people find workarounds around new procedures, the new talent development programme is received cynically and so on.

An ethnographic approach—i.e., trying to study the issue through the eyes of the staff themselves—can complement or refine design. This often entails talking to people from a blank slate as much as that is possible, instead of observing people through our own or preconceived value systems. So, rather than asking “Why do these people work so inefficiently?” when observing them, a more ethnographic stance would be asking “How do these people do their work exactly, and why do they do what they do?”

So wanting to know how, say, hybrid ways of working need to be organised in a company requires going back to basics. Workers could for instance, be involved in the design and decision-making process of new ways of working. Not as an afterthought, or as a ‘check-the-boxes’ exercise to show you listened to staff, but from the very beginning.

Eileen: This brings to mind how the Hybrid Pyramid was applied in an agency. ILOD was supporting various divisions in discussing their hybrid working norms. While there were organisational-level principles to guide the norms, it was clear that the nature of work and work needs varied across divisions. The leadership recognised this early on and gave each director discretion to decide on their division-level norms. There were divisions where staff wanted to meet together more frequently to discuss work, for example, in designing outreach sessions. In other divisions, such as the finance team, staff appreciated the ability to work remotely to do deep work. Even when we compared the research team in one agency to the research unit in another agency, we found different practices in the mode and frequency of interactions. The former found they could be as productive working virtually as in person, while the latter opted to return to the office on some fixed days. In these real-life cases, a blanket or top-down implementation would not have benefited different needs across the organisation. Understanding the views of people on the ground whose perspectives, needs and optimal working styles may be less visible to senior management can indeed make a difference.

Thijs: To add a further example, in my own work on inter-organisational collaboration, I studied a newly established multimillion-dollar coordination centre where employees from different organisations were located in one office to facilitate collaboration.11 A lot of manpower and money was spent on the design of the centre, with even the design and layout of the furniture aiming to direct lines of sight so that each employee would constantly have the people of other organisations in the corner of their eyes.

In practice, however, I found not just inter-organisational collaboration but also—and much stronger so—resistance to this, that I have described as territorial practices. The kitchen, for instance, was meant to become a space where people of different organisations would meet and share meals. But in the first weeks, fridges and cabinets were earmarked and name-tagged: this common fridge became that department’s fridge; these shared cabinets became their cabinets.

The study shows the limits of organisational design done in a top-down matter. You need to know what is going on in the daily lives of the employees on which you ‘force’—no matter how good the intentions—a different way of working.

A blanket or top-down implementation would not benefit different needs across an organisation.

Eileen: If organisations were to carry out organisational ethnography, what do they need to watch out for?

Thijs: Ethnographers in general believe that our worlds are socially constructed and, thus, knowing the world of others requires deep interpretation rather than measurement. It is based on the realisation that our societies, and how our workplaces operate, are much messier and more complex than any statistical model can capture.

So, ethnography is about giving voice to multiple groups of people in a society, culture, workplace, and so on. There are two ideas behind this. First, multivocality: if everyone tells you exactly the same thing, something is off. The goal is to find sub-cultures, disagreements, tensions, and so on. Second, surfacing non-dominant voices in a workplace.

Taking these principles in account, I would advise against using—or actually abusing—ethnography as a way, for example, to reinforce decisions that have already been made. Ethnography is a bottom-up perspective that puts people in a specific position in which they—not their manager, not even the CEO—are the expert in the topic you are interested in. That’s the power of it. If the intentions are not genuine, if it is being used simply as a way to get buy-in from people, I would say better use another methodology to legitimise whatever decision has been made. And even with genuine intentions, it can take time to build trust and rapport with the people you want to learn about.

An ethnographer also needs to carefully manage the dual identities of being an insider and being an outsider. Ethnography is the art of becoming an insider while remaining an outsider. If you fail in the latter you have, as ethnographers describe it, “gone native”: much of what you want to study or know or understand has then become implicit, which makes it extremely hard to observe. Using the words of my old university teachers, outsiders need to work hard to “make the strange familiar”, whereas insiders need to engage in the opposite process of “making the familiar strange”.12

In organisational practice, this entails juggling different roles: a more empathetic one in which you intimately try to understand the people you study; and a more analytical one in which you try to make sense of this in relation to theory, corporate ambitions, broader societal trends, and so on. For instance, when studying hybrid work ethnographically, the things you hear, learn and see from the participants in your study—whilst perhaps most important—are in themselves not sufficient in providing any recommendations or interventions. For this, these local experiences must be put in conversation with more global trends about the future of work, digitalisation, the direction the company wants to be heading, and so on.

Eileen: By focusing on what people actually do in the workplace and why, ethnography re-establishes people-centricity in organisations. Organisations are made up of people, but people’s needs are sometimes forgotten in work processes and deliverables imposed centrally or from the top down.

Recently, I ran a discussion session for a division who was embarking on a shared desk office set-up in their hybrid working norms. To ensure parity, the management had demarcated sitting zones in the office for different teams. During the session, an officer raised a question about sitting in a zone for another team if the seat was not occupied that day. Everyone chimed in with similar observations and concerns for fear of encroaching on others’ space. The conclusion was that people could sit anywhere unoccupied. While this might appear to be common sense to someone on the outside, the discussion allowed real-world needs to be voiced, leading to explicit permission implicitly sought by staff. This example shows how in marrying an ethnographic, people-centric lens with analytical thinking, we could be more effective and successful to achieve the intended outcomes of a hybrid work design.

Taking a Practical Step Forward

Conversations on hybrid work tend to revolve about the number of days staff are required to be back in office or allowed to be working from home. The deeper underlying question to this is about the degree of flexibility and autonomy staff members get in deciding when and where to meet work deliverables. Establishing what flexibility and autonomy will look like depends on how well we understand people’s needs and situations. This will vary across teams and across organisations. That is where ethnography can play an important role.

For example, in the dimension of “well-designed structure and interactions” in the Hybrid Pyramid, we can ask the 5W1H questions to people on the ground:

- Who do you talk to get your work done?

- What do you do with those people?

- When do you talk to them? (How frequent?)

- Where do you go and find them?

- Why do you talk to them?

- How do you figure out who to talk to?

Their responses can tell us how they work within and across structural levels. We can also probe how often do they refer to an organisational chart or internal directory. Comparing these data with the design intentions for the organisation structure can help us improve the hybrid work design. It allows us to make a tangible reference to ground reality versus abstract drawings of boxes and lines determined centrally or imposed from the top.

Ethnography encourages us to step back, suspend our assumptions and judgements, and observe how our people actually get their work done. Such an approach can help organisations assess how effective their hybrid work practices really are, so the right adjustments can be made to grow and sustain effective and productive results.

For example, a recent article highlighted a survey finding of remote workers spending their break times to run errands, exercise, and do chores besides being on their mobile devices.13

In-office workers spend more time on computer games for their mental breaks—likely because they can’t accomplish much else in the office!

No one model of work will fit all employees or across different organisations. Instead, well-designed hybrid work could provide individuals with the flexibility and autonomy to balance their work deliverables with their individual life needs (including caregiving, exercise and mental wellbeing). As a more empathetic and flexible way of working, hybrid work practices that are sensitive to how individuals best live, work and play, could lead to more engaged staff and more productive outcomes.

Notes

- J. M. Barrero, N. Bloom, and S. J. Davis, “The Evolution of Working from Home”, Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research (SIEPR), July, 2023, https://siepr.stanford.edu/publications/working-paper/evolution-working-home.

- Sueann Soon, “The Leader’s Playbook to Hybrid Work”, May, 2022, https://gccprod.sharepoint.com/sites/CSC-LnODinsights/SitePages/The-Leader%27s-Playbook-to-Hybrid-Work.aspx?web=1.

(Note: This link is only be accessible to public officers with SharePoint access.) - Jacob Zinkula, “The RTO Push Is Over. Hybrid Work Has Won Out, Says Nation's Top Remote-Work Expert”, Insider, July 11, 2023, https://www.businessinsider.com/hybrid-working-model-wfh-work-from-home-policy-office-trends-2023-7.

- C. G. Aksoy, J. M. Barrero, N. Bloom, S. J. Davis, M. Dolls, and P. Zarate, “Working from Home Around the Globe: 2023 Report”, 28 June, 2023, https://wfhresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/GSWA-2023.pdf.

- “The Fight Over Working from Home Goes Global”, The Economist, July 10, 2023, https://www.economist.com/business/2023/07/10/the-fight-over-working-from-home-goes-global.

- See Note 1.

- See Note 4.

- See Note 1.

- Ibid.

- A. L., Fayard and J. Weeks, “Photocopiers and Water-Coolers: The Affordances of Informal Interaction”, Organization Studies 28, no. 5 (2007): 605–634.

- T. Willems and A. Marrewijk, “Building Collaboration? Co-location and “Dis-location” in a Railway Control Post”, Revista de Administração de Empresas, 57 (2017): 542-554.

- S. B. Ybema and F. H. Kamsteeg, (2009). “Making the Familiar Strange: A Case for Disengaged Organizational Ethnography”, in Organizational Ethnography: Studying the Complexities of Everyday Life, eds S.B. Ybema, D. Yanow, H. Wels, and F. H. Kamsteeg (Sage, 2009), 101–119.

- Richard Bernstein Advisors, comment on Twitter, July 24, 2023, 11:12 p.m., https://twitter.com/rbadvisors/status/1683495376622419970?s=46&t=SrKfTBEHtSfP_IEQ-EjVDg.