Encouraging Innovation for A More Sustainable Built Environment

Digital Issue 09, Nov 2022

In light of climate concerns, there has been a move towards more sustainable development, and growing interest in innovative technologies to help achieve this in the built environment. However, a number of challenges hinder these innovations from being implemented more broadly on a commercial scale.

First, innovative technologies are often seen as riskier or more costly to adopt, requiring higher upfront capital expenditure (CapEx). This can deter risk-averse investors or developers who are not sure if they can realise benefits over the lifecycle of longer-term sustainability projects.

Second, many residential projects are undertaken on a develop-and-sell system. This means that developers are often not the eventual building owners, and do not benefit from the lifecycle cost savings from improved sustainability performance. At the same time, buyers of such projects are seen as less willing to pay more for greener buildings.1

Despite these challenges, a number of projects in Singapore have applied novel approaches to successfully incorporate or scale up sustainable urban solutions.

Innovative technologies are often seen as riskier or more costly to adopt.

Building an Effective Public-Private Partnership for Innovation

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) can play an important role in mitigating risks and upfront investment costs when adopting sustainable technologies.

In Singapore, the Housing and Development Board (HDB) has been a pioneer in providing eco-friendly and innovative features for smart and sustainable living, and plays a critical role in leading innovation as part of its core sustainability strategy.

To mitigate technical risks, the HDB set up the Centre of Building Research (CBR) to spearhead research and development (R&D) efforts in building and environmental sustainability. New innovative technologies are then piloted in its public housing projects, which then offer insights towards effectively scaling up such innovations across Singapore. Successful pilots also help to assuage concerns from the private sector on the viability of sustainability technologies at scale. In some cases, the HDB also offers private sector partners the opportunity and space to test innovation projects.

Financially, the HDB shares business risks with the private sector partners by co-investing in sustainable infrastructures, such as Centralised Cooling Systems (CCSs) and solar photovoltaic (PV) systems. At the same time, partnering with the HDB helps to build market demand and economies of scale for such innovations, which drives down costs for potential technology adopters. Innovations in business models can help to encourage the uptake of sustainability technologies by transferring the risks of innovation from the building owner and consumer to the solution provider, while ensuring financial viability.

Successful pilots help to assuage concerns from the private sector on the viability of sustainability technologies at scale.

Implementing a Centralised Cooling System (CCS)

Figure 1. Tengah DCS

Source: SP Group

The HDB partnered with SP Group to implement a CCS for Tengah Town to provide energy-efficient cooling to homes. SP Group’s role was to finance, design, build and operate the CCS while HDB designed the building infrastructure to support the installation of the CCS. This model greatly reduced the risk to HDB as SP Group was in a better position to operate and maintain the cooling system.

In return for their initial investment and provision of services, SP Group will earn revenue from Tengah residents through fees (such as for installation and servicing) and the sale of cooling services. Since profits are derived from the sale of cooling, SP Group is incentivised to upgrade the equipment and continue innovating to optimise the performance of the CCS.

Partnering with HDB offered SP Group the opportunity to test the CCS deployment for residential developments. With the CCS as an anchor, SP Group was also able to introduce and test out other energy-related innovations—including solar PV systems, battery energy storage systems, electric vehicle (EV) charging stations, data platforms and digital technologies—to expand beyond its primary remit.

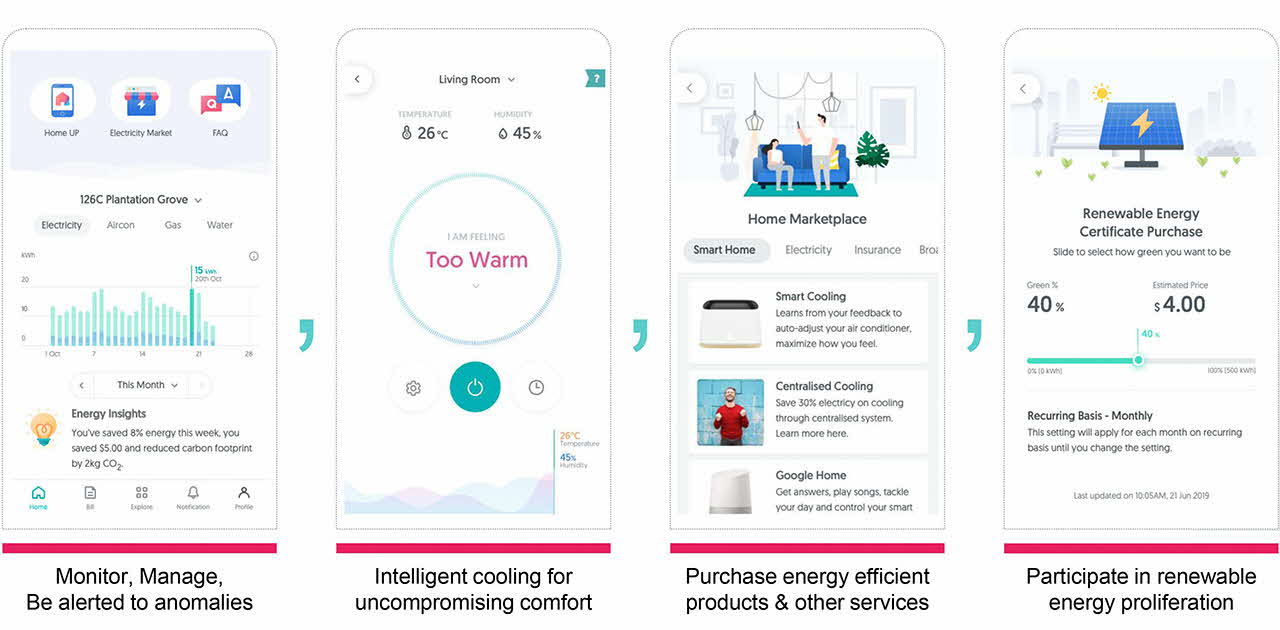

Figure 2. Tengah CCS Township App

Source: SP Group

The HDB partnered with SP Group to implement a CCS for Tengah Town to provide energy-efficient cooling to homes. SP Group’s role was to finance, design, build and operate the CCS while HDB designed the building infrastructure to support the installation of the CCS. This model greatly reduced the risk to HDB as SP Group was in a better position to operate and maintain the cooling system.

In return for their initial investment and provision of services, SP Group will earn revenue from Tengah residents through fees (such as for installation and servicing) and the sale of cooling services. Since profits are derived from the sale of cooling, SP Group is incentivised to upgrade the equipment and continue innovating to optimise the performance of the CCS.

Partnering with HDB offered SP Group the opportunity to test the CCS deployment for residential developments. With the CCS as an anchor, SP Group was also able to introduce and test out other energy-related innovations—including solar PV systems, battery energy storage systems, electric vehicle (EV) charging stations, data platforms and digital technologies—to expand beyond its primary remit.

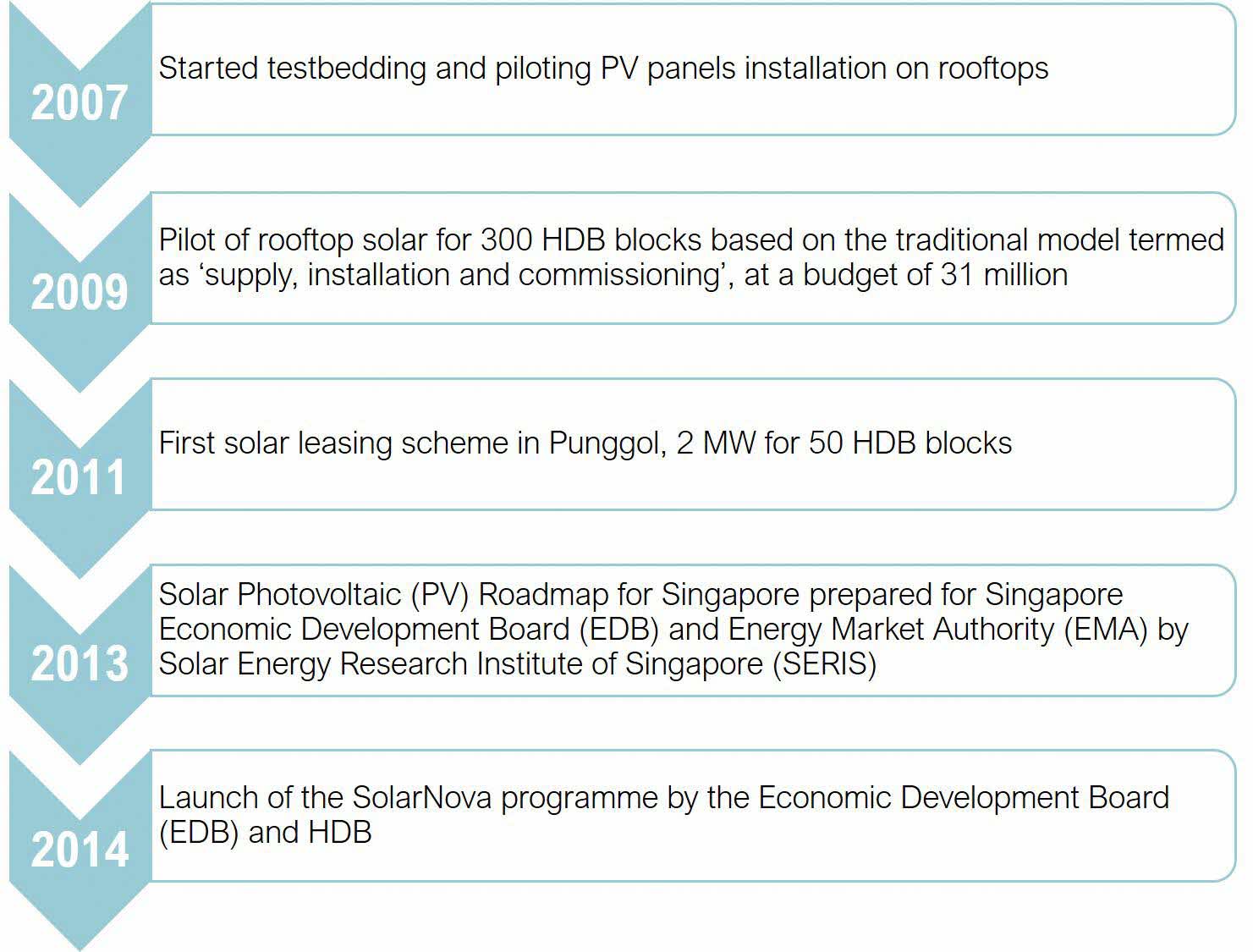

Such approaches support the industry in developing its capabilities. They were key to the scaling up of HDB’s solar PV system implementation efforts in a financially sustainable manner. The success of the solar leasing model led to the creation of the SolarNova programme in 2014.

Under the SolarNova Programme, Sunseap installs solar panels across Singapore.

Source: Sunseap

Scaling Up Deployment of Solar PV Systems through a Solar Leasing Model

Although Singapore had strategically pushed for solar PV systems since 2007, the cost of installing and maintaining solar PV systems remained a significant barrier to scaling up their adoption. In response, HDB and the Economic Development Board (EDB) initiated the SolarNova programme in 2014 as a whole-of-government effort to accelerate the deployment of solar PV systems in Singapore.

The solar leasing model reduces the project’s capital expenditure (CapEx) and operating expenditure (OpEx), and hence the associated financial risks for the customer (i.e., Town Councils or government agencies). The customer does not need to acquire or develop capabilities in maintaining the system, nor bear the costs of retiring solar panels when they have reached end-of-life. In return, solar vendors profit from the sale of solar energy to the customers.

Figure 1. Milestones of the SolarNova Programme

Key Challenges and Learning Points

Three key factors contributed to the scaling up of the solar leasing model.

1. The model helped to manage business risks and make projects bankable for the solution provider to take on the risk of high CapEx and OpEx. The SolarNova tenders, by design, are meant to aggregate bulk demand for solar PV systems across government agencies, achieving economies of scale and making the projects financially viable for the industry. For example, two-thirds of the demand for Sunseap’s projects come from government projects.

2. A long service contract is needed to give the solution provider time to recover CapEx and make profits. In the solar leasing case, contracts were usually 20 to 30 years long, to allow time for vendors to make profits through the sale of solar energy generated.

3. Benefit sharing helped to encourage uptake and support for the implementation of the solar PV systems. Under the SolarNova programme, harnessed solar energy is first used to power common services in HDB estates in the day. The solar vendors then sells excess solar energy generated to the grid, with the revenue shared with customers. This encourages the customer Town Councils and agencies to actively support the deployment of the solar PV systems in their buildings.

Innovative Operations and Behavioural Change

Innovative approaches in building operations can stimulate the uptake of sustainability technologies and encouraging behavioural change.

The National University of Singapore (NUS) School of Design and Environment 4 Building (SDE4) is Singapore’s first new-build net-zero energy building. It began operating in January 2019. As a developer-owner-operator, NUS oversaw the conceptualisation, development and operation of its new campus infrastructure. This encouraged it to adopt a holistic lifecycle approach, translating ambitious goals into an optimised design, facilitating sustainable downstream operations and performance.

Innovative approaches in building operations can stimulate the uptake of sustainability technologies and encouraging behavioural change.

The NUS took the unconventional path of procuring the design for SDE4 through an international competition in 2013.

Singapore’s First New-Build Net-Zero Energy Building

NUS SDE4

Credits: Courtesy of NUS College of Design and Engineering and Serie Architects. Photography by Rory Gardiner.

Aspirational Target-setting for Sustainability

The NUS took the unconventional path of procuring the design for SDE4 through an international competition in 2013. Beyond the standard architectural brief, the competition brief specified the performance requirements needed to achieve the aspirational target of a net-zero energy building. This included a strategic statement with six building performance mandates: spatial, acoustic, lighting, air quality, comfort, and maintainability.

London-based Serie Architects and Singapore-based Multiply Architects won the international competition and designed the SDE4 with climate-focused architecture and new energy-efficient structures. Key sustainability design features of SDE4 include an extensive array of more than 1,200 solar PV panels; a large-scale hybrid cooling system augmented with elevated air speeds from ceiling fans; and tropical architecture that enhances daylight utilisation.

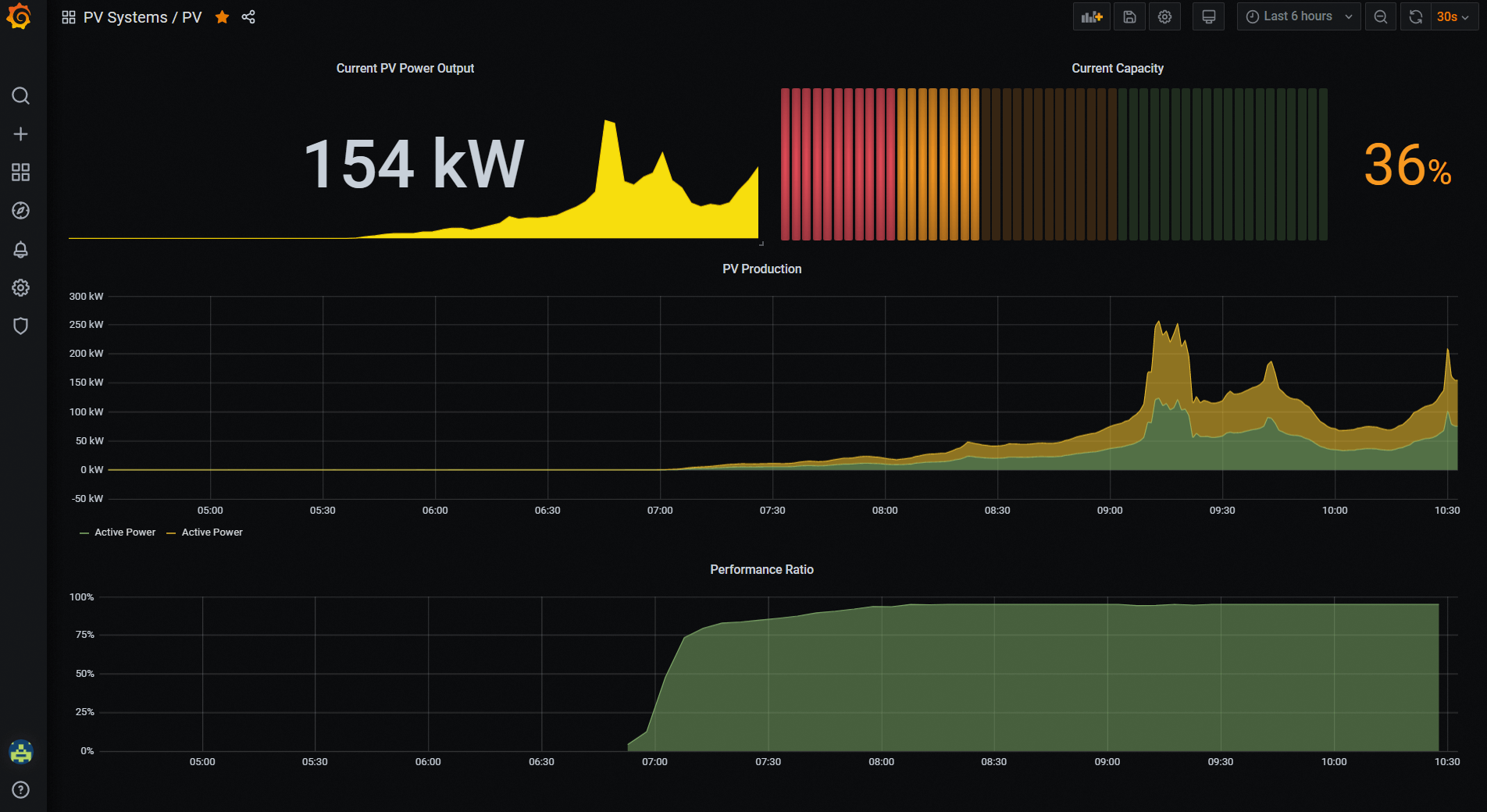

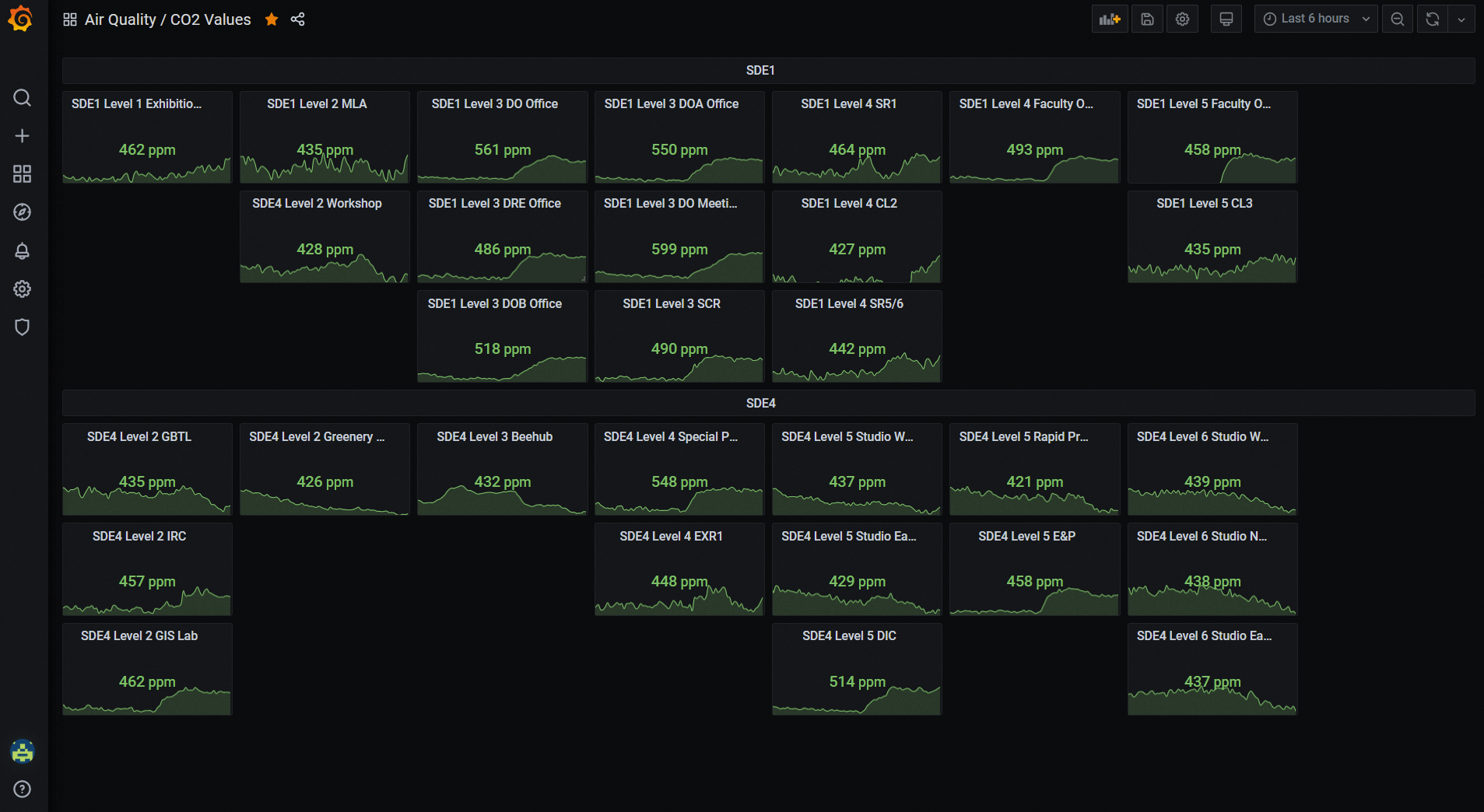

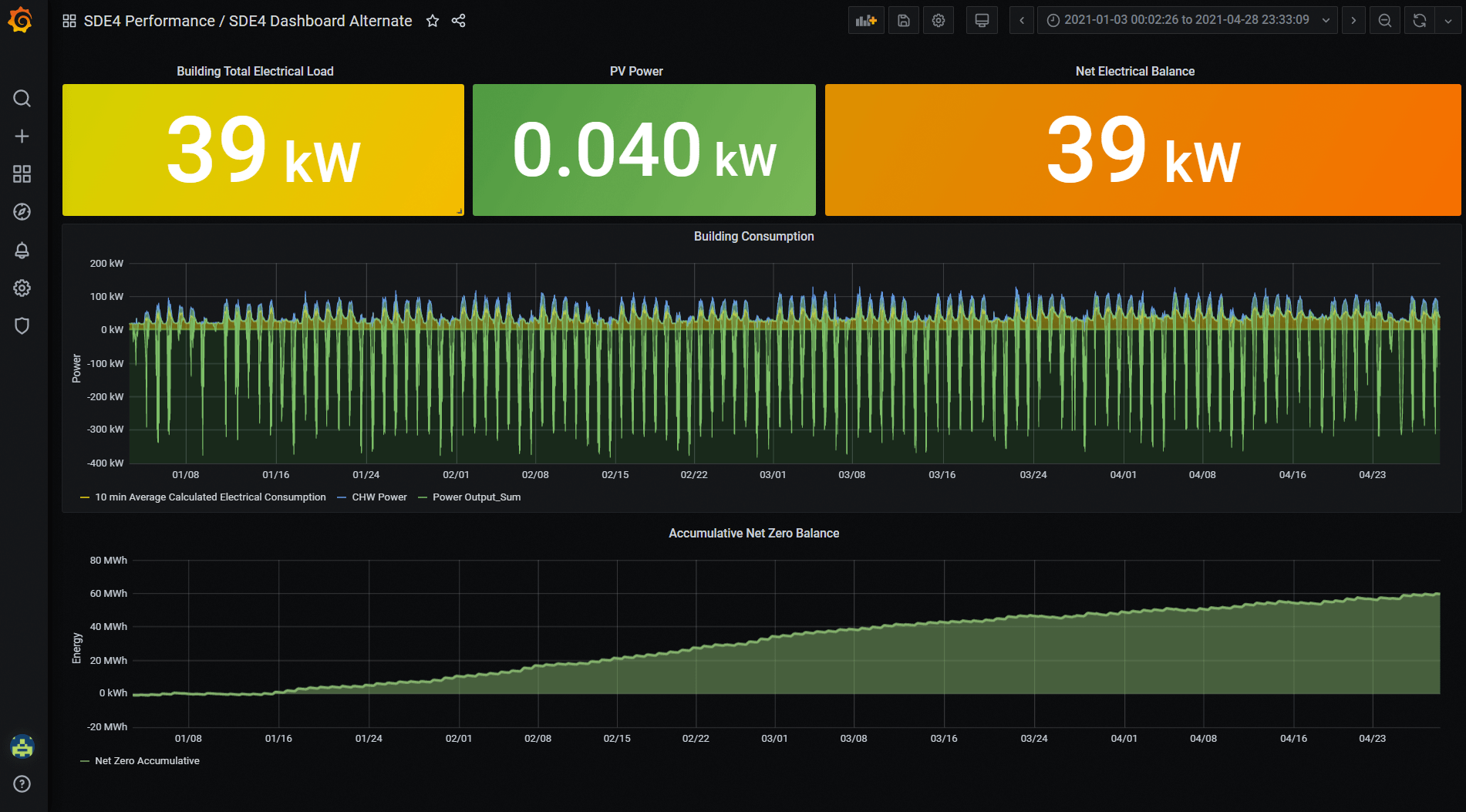

Data-Driven Facility Management

Sustainability goals and targets set at the design stage must be planned for in the development phase and followed through after the building’s completion into the operational stage. Early in the development phase, SDE4 put in place a building management system (BMS) and sensors for pervasive data collection, as well as a dashboard to monitor SDE4’s performance in-house, rather than leaving it as an afterthought.

Together, the sensors and dashboard measure and track various indicators of environmental quality and sustainability, including carbon dioxide levels, solar PV energy production and capacity, and overall building energy performance. This allows SDE4 to optimise energy efficiency while ensuring the comfort of users.

Figure 1. The solar PV monitoring dashboard displays the overall PV power output, production, current capacity, and performance ratio.

Source: NUS SDE

Figure 2. The Indoor Environmental Quality Monitoring dashboard displays the carbon dioxide level of various rooms in both SDE1 and SDE4.

Source: NUS SDE

Figure 3. The dashboard displays the overall energy performance of SDE4 across days, including the accumulative net-zero balance during the chosen period.

Source: NUS SDE

Nudging Sustainability Behaviour

Beyond adopting technologies and data analysis, the SDE4 management have been conscientious in cultivating a culture of sustainability. Students, the major users of SDE4, have themselves adopted the goal of achieving a net-zero energy target.

Apart from having visible reminders to encourage users to turn off projector screens after classes, SDE4 has developed a mobile application that informs users of the room temperature, humidity and air quality. Based on room conditions, the app offers recommendations to nudge user behaviour and reduce energy consumption—reminding them, for example, to switch off the air-conditioning and open the windows to allow for natural ventilation.

Figure 4. A screenshot of the mobile application that nudges users to reduce energy consumption.

Source: NUS SDE

Exceeding Performance Expectations

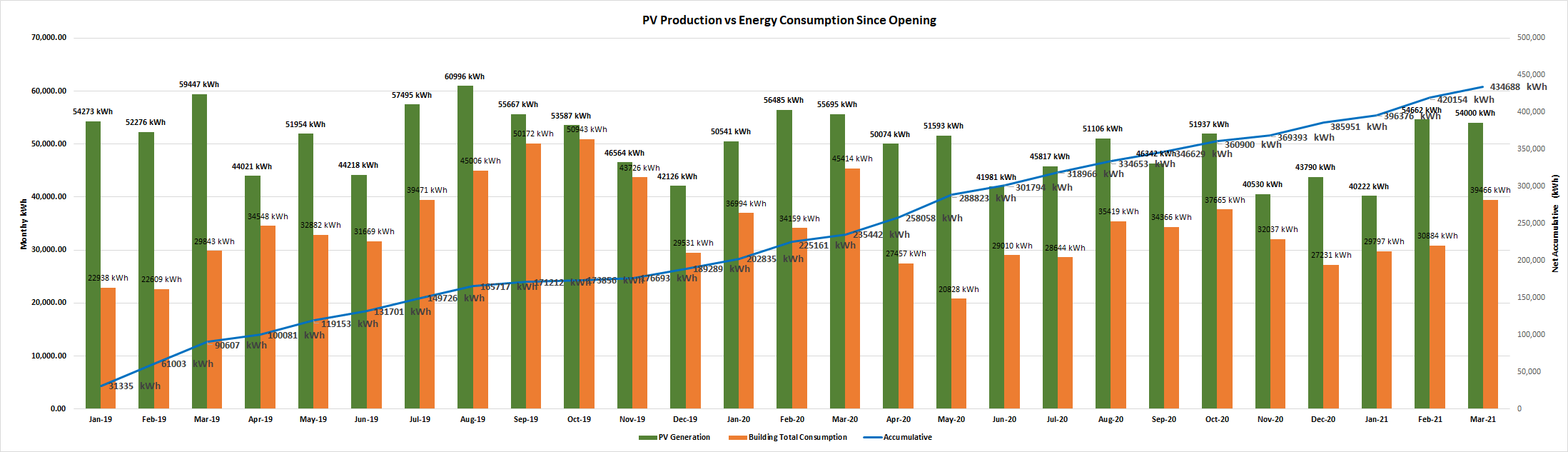

Since its opening in January 2019, SDE4 has achieved net-positive in its energy balance for two consecutive years: equivalent to saving almost six months’ worth of energy. The Energy Usage Intensity (EUI), which measures the building’s annual energy consumption relative to its gross floor area, has also been halved in the same period.

Figure 5. Accumulative increase in SDE4's net-positive energy balance since January 2019.

Source: NUS SDE

With its developer-owner-operator model, SDE4 was incentivised to adopt an innovative approach for its operations, integrating the front end (through ambitious target setting and optimised sustainable design at the design stage) with the back end (through pervasive data collection and behavioural nudging).

SDE4 has won numerous accolades, including the Zero Energy Certification by the International Living Future Institute (ILFI), and the Green Mark Platinum Certification and Super Low-Energy Building Award by the BCA.

Conclusion: Key Lessons

In seeking to commercialise sustainability solutions, the built environment sector is critical. The examples above highlight the potential for adopting sustainability innovations in Singapore. They also suggest insights on how they might be scaled up further or deployed elsewhere.

1. An effective partnership framework among government agencies, developers and solution providers can create enabling conditions for innovations to take place. First, it allows the sharing of risks among the various players in the urban solutions space. Second, it provides a platform and opportunity to experiment with innovative business models and novel sustainability solutions—from pilots to limit technological risks, to deployment at scale with the necessary adjustments or further investments. Third, it can make use of regulatory sandboxing for proof-of-concept trials, and to gain user buy-in that can go a long way in building market demand for such technologies.

2. Business model innovation lowers the barriers to deploy sustainability technologies by balancing the risks between the building owner and the solution provider. It can allow for a palatable level of risk-sharing between public sector developers and urban solution providers, as seen with the deployment of the CCS in Tengah and solar PV systems for the SolarNova programme.

3. Taking a long-term view to account of longer-term returns for investments for large-scale sustainability solutions, with an appropriate contingency plan, is vital. In some cases, long service contracts may provide sufficient time for solution providers to recoup high CapEx costs and become profitable. At the same time, there is a need for a contingency plan for different stages of the contract, and some degree of flexibility for termination, if critical conditions are not fulfilled.

4. Designing for optionality can allow for upgrades over the lifetime of use. Business models and contracts should be designed to incentivise solution providers to upgrade their infrastructures as technology advances. This helps to push solution providers to continue innovating to remain competitive and achieve better sustainability performance to increase their profits.

5. Innovative operations that integrate lifecycle considerations help encourage the implementation of sustainability technologies to obtain downstream benefits. NUS SDE4 adopted an innovative approach that integrated its front-end (design and procurement) and back-end (operations) processes. This encouraged NUS to set ambitious targets and integrate sustainability technologies from the design stage which allowed SDE4 to achieve high sustainability performance in its operations.

6. Adopting an urban systems approach will better integrate the planning and design of the built environment with sustainability innovations. For example, the Tengah CCS evolved through HDB’s and SP’s collaboration to implement an integrated energy system that integrates district cooling, renewable energy, waste-to-energy and EV charging systems, with digital dashboards to encourage sustainable behaviour in energy use.

Business models and contracts should be designed to incentivise solution providers to upgrade their infrastructures as technology advances.

NOTE

- Richard Wong, Abhineet Kaul and Xiu Wei, “Perception towards Green Buildings in Singapore”, accessed July 1, 2022, https://www1.bca.gov.sg/docs/default-source/docs-corp-buildsg/sustainability/summary_report_survey_on_bca_green_mark.pdf.