Good Governance Is Built on Capabilities, Not Ideology

Digital Edition Issue 8, Apr 2022

The Global Governance Gap

There is a widening chasm between what populations expect from their governments today and what their governments are delivering. This ‘governance gap’ can be seen across every continent and all forms of government.

Around the world, discontent with governments has risen, trust in them has fallen. Research by the UN across a mix of 62 developed and developing countries found that in 2006, an average of 46% of people expressed confidence or trust in their government.1

In 2019, only 36% felt that way. Separate surveys from the UN found the COVID-19 pandemic briefly improved citizens’ trust in their governments, but that “trust in national Governments [has since] reverted to its (low) pre-pandemic levels.”2

Ideologies Are not the Answer

This governance gap and trust deficit are widening at a time when governments face historic challenges, from a global pandemic to climate change, rising inequality to declining social mobility. Discussions of how to help governments meet these challenges often focus on political systems and ideologies. The implication seems to be that identifying and implementing the ‘right’ ideology or political systems is the key step to turning things around.

Ideologies and political systems do matter—wars have been fought over them and governments overthrown—but they are often slippery and divisive. How does one reconcile, for instance, that in any given election, multiple candidates will proclaim themselves champions of democracy, yet will hold contrasting views on the role of government, the level of taxation, and even the boundaries of personal responsibility and freedom? Deng Xiaoping and Mao Zedong were both Communist leaders, and Charles de Gaulle and Jawaharlal Nehru both Socialist, yet each took a very different approach from the other.

Capabilities Offer a Concrete Focus

Capabilities are a practical place to begin a discussion of good governance. We can all agree that a government that makes good use of evidence and data, engages and communicates well with stakeholders, stewards public funds with accountability and care, and hires and promotes based on merit—is a good government, regardless of the ideology it identifies with.

As part of our work for the Chandler Institute of Governance (CIG), a non-governmental non-profit organisation that partners and works with national and local governments, we spent two years connecting with government practitioners across more than 20 countries. These practitioners’ countries differed widely in ideologies and income levels, yet all were in basic agreement about the core components of good governance.

Capabilities are a practical place to begin a discussion of good governance.

Measuring Government Capabilities

Those conversations helped us to create a new index that focuses on the capabilities of 104 governments, covering about 90% of the world’s population, making it the most comprehensive index of its kind. The Chandler Good Government Index (CGGI) is unique in its focus on government capabilities, rather than outcomes alone. The CGGI comprises 35 indicators—26 focused on government capabilities, 9 on key outcomes that citizens and businesses care about—drawn from more than 50 publicly available global data sources.

Because it focuses on capabilities, the Index offers a neutral way to talk about good government, across the political spectrum. The CGGI was designed to help governments benchmark their capabilities against peers and provide data-driven insights into how those capabilities strengthen or weaken over time.

Capabilities are so crucial because they tend to be more within a government’s control than outcomes alone, which can often be influenced by external forces. In deciding which capabilities to measure and how to capture them, we combined our team’s public sector experience with insights from other governance practitioners. We then validated these findings with an Advisory Panel of eight global governance experts.3

Capabilities are crucial because they tend to be more within a government’s control than outcomes alone, which can often be influenced by external forces.

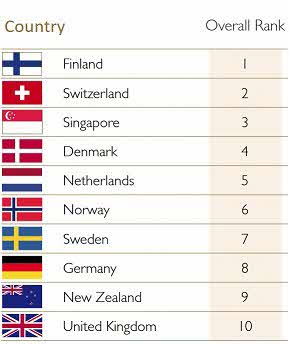

Singapore Ranks Third in Our Index

Singapore ranked third in our inaugural index last year and has maintained its ranking in the 2022 Index this year. This highlights the depth and range of the government's capabilities. The full list of country ranks can be found in the Index Report.4

Figure 1. Singapore’s strong performance in the Chandler Good Governance Index

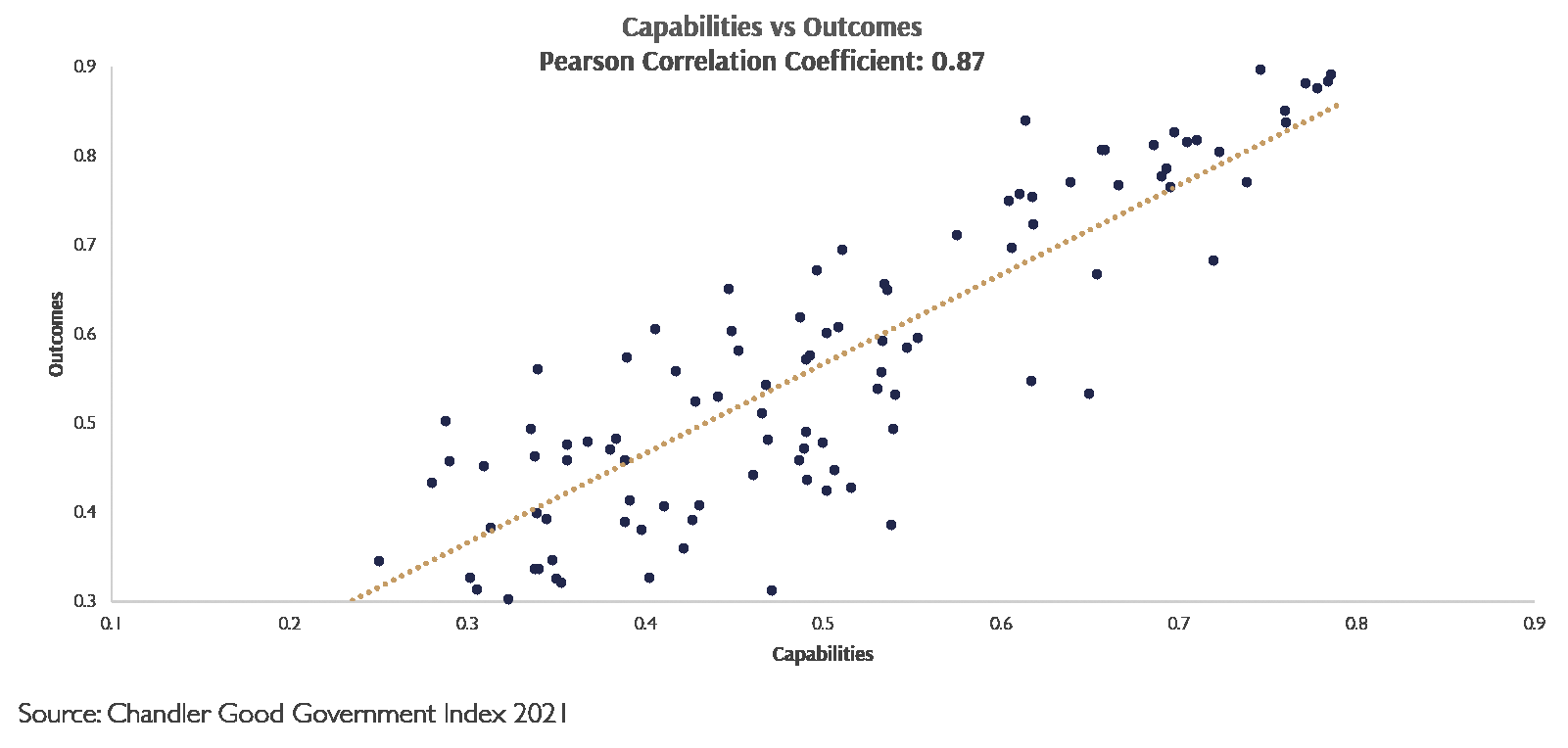

The Link between Capabilities and Outcomes

Perhaps the most powerful insight that emerged from the CGGI was that governments with strong capabilities deliver better outcomes than governments with weaker capabilities. This might sound obvious, but it tells us that improving government capabilities is essential if we want to improve the outcomes people enjoy in their daily lives, ranging from healthcare and education to environmental protection.

Figure 2. A strong link between governments’ capabilities and the outcomes they produce. Source: Chandler Good Government Index 2022

It is empowering that stronger government capabilities are linked with better outcomes, because many capabilities can be learnt and improved over time.

Stronger government capabilities are linked with better outcomes.

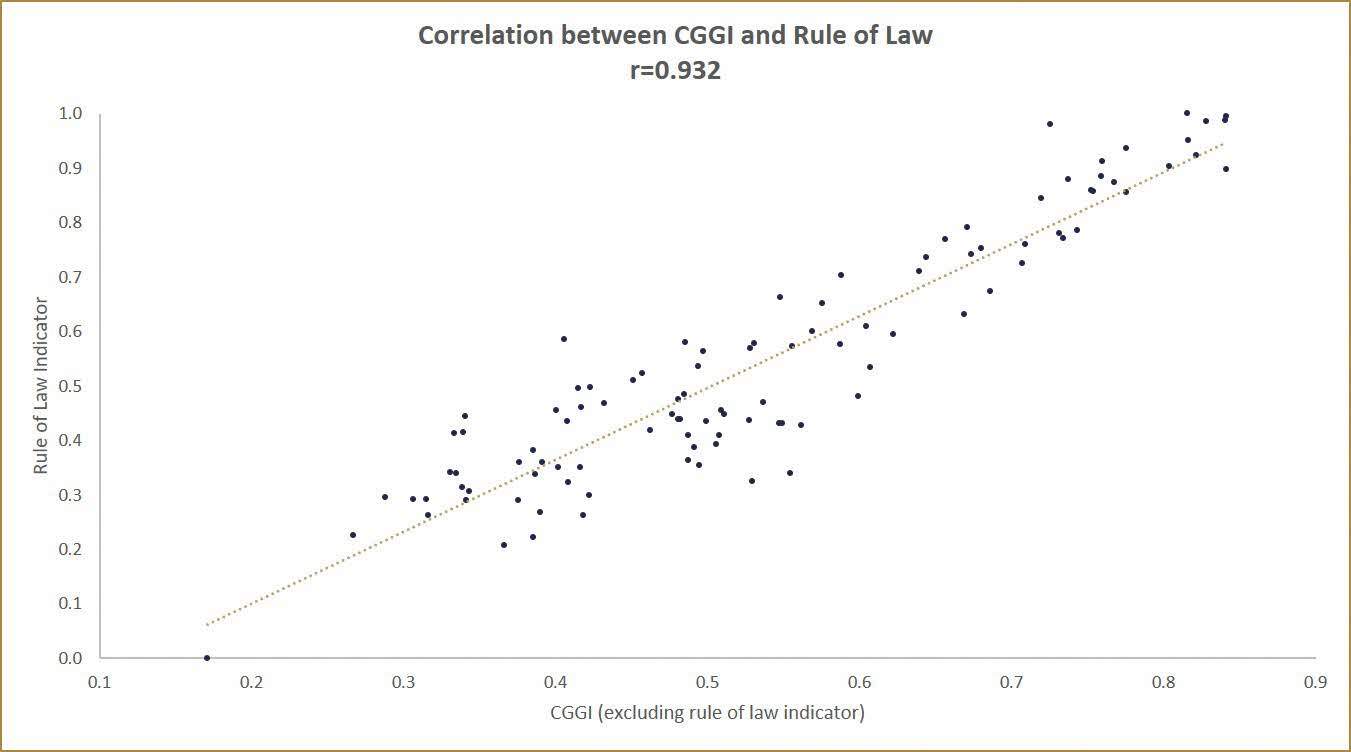

No capability is more important in good governance than rule of law

The capability most closely related to good governance, according to our findings, is rule of law—a trend that held true regardless of income level, ideology, or geography.

Figure 3. Of the 26 governance capabilities analysed by the CGGI, rule of law was most closely associated with good governance. Source: Chandler Good Government Index 2022, Rule of Law Indicator (World Justice Project and Worldwide Governance Indicators)

Supporting Governments to Develop their Capabilities

CIG’s mandate is to support governments globally in capability development. A large part of this involves delivering training for public servants, for which we have set up the Chandler Academy of Governance (CAG).

As former civil servants in Singapore, we were fortunate to have benefitted from an environment that values and respects staff development and training. But our experience working internationally is that this should not be taken for granted. Many public servants globally do not have that support—even as citizen and investor demands continue to rise.

At CAG, our curriculum is designed around three fundamental beliefs that reflect our vision of the capabilities that governments need. These are independent of political system or ideology.

1. Leaders as National Stewards

First, we believe that governments need leaders who are effective national stewards. By that we mean leaders who safeguard the national story from one generation to the next, and in doing do, build trust with the people they serve.

This starts by discerning a nation’s story, a task that demands a deep appreciation and respect of the nation’s history, its past and current context, and the values, cultures and needs of its constituents. Second, it involves communicating that story effectively, while finding ways to develop policies and programmes aligned with that narrative. Finally, leaders would also need to steer policy in line with the national story, even as it evolves.

This is not an alien concept in Singapore, even if the term ‘national story’ is not as frequently used. For example, a few core tenets—such as meritocracy, openness to the world, and racial and religious harmony—have defined Singapore’s national story and been prominent considerations in the design of key policies.

Doing this well will require the right capabilities. For example, leaders need the foresight tools to help them better anticipate risks and changes in the country’s operating environment. They need the ability to conduct meaningful public consultation and engagement exercises to discern public sentiments.

Governments need leaders who are effective national stewards. By that we mean a leader who safeguards the national story from one generation to the next.

2. Strong Organisations and Systems

Second, we believe that the public sector must have strong organisations and systems: that are united in purpose, values, and culture, and structured in the best way to fulfil their respective missions and mandates. These concepts—values, mission, culture—are all too often treated as plaques on the wall, rather than key responsibilities of senior leaders.

Strong organisations must also be supported by effective systems, such as HR and performance management systems, resource budgeting and procurement, as well as strategic planning. These are the basic ‘plumbing’ of any effective organisation. System choices matter—just moving from a paper-based procurement system to one that is electronic can yield profound benefits in efficiency, transparency and corruption control.

The public sector must have strong organisations and systems: that are united in purpose, values, and culture, and structured in the best way to fulfil their respective missions.

3. Building Skills in Policy and Programme Design, and Implementation

Finally, we believe that public servants must be skilled in policy and programme design, and implementation. Policies and programmes are the main products and services that governments provide, and the main vehicle through which governments serve their constituents.

This involves supporting public servants with technical capabilities to craft policies in line with their intended outcomes, the wisdom to discern whether policies are politically tenable, and the capacity to work together at the whole-of-government level to translate policy on paper to implementation on the ground. Specific capabilities include the use of data in evidence-based policy analysis, policy writing and presentation, internal and external stakeholder engagement and communication, and project management.

Public servants must be skilled in policy and programme design, and implementation.

Investing in Capability Development Is a Recipe for Progress

These capabilities may sound familiar, even banal. Yet in our experience, implementing a coherent, structured system of training for public servants is far from mundane. It requires strong political will and a culture of continual learning. It demands ongoing investments—of money, time, and manpower—and requires thoughtfully designed courses and practitioner-focused learning. Each of these is much easier to write than it is to implement—and so few do it brilliantly.

But, as Singapore demonstrates, such a training system delivers results that more than justify the effort. By consistently investing in training its public servants, whether through structured training programmes at the Civil Service College, or through rigorous on-the-job learning, Singapore has positioned itself as one of the world’s most respected and efficient governance systems. In the inaugural CGGI, Singapore topped quite a few indicators, including ‘long-term vision’ and ‘quality of bureaucracy’.

Singapore’s system has benefitted us both professionally and personally, and it continues to inspire and inform our efforts to provide training and support to governance practitioners around the world.

Implementing a coherent, structured system of training for public servants requires strong political will and a culture of continuous learning.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Wu Wei Neng is the Executive Director of the Chandler Institute of Governance. He holds adjunct appointments with the Centre for Liveable Cities, Ministry of National Development, and the Singapore Civil Service College. He previously worked in public policy design and implementation in the Singapore Ministry of Trade and Industry and Ministry of Defence, and in training and development work at the Civil Service College.

Kenneth Sim is Dean of the Chandler Academy of Governance, and Deputy Executive Director of the Chandler Institute of Governance. Before joining CIG, Kenneth spent over 15 years in the Singapore Public Service, in varied portfolios including industry development, skills development and training, casino regulation, energy policy and environmental sustainability. He was formerly Special Assistant to the Deputy Prime Minister.

NOTES

- Jonathan Perry, “Trust in Public Institutions: Trends and Implications for Economic Security”, July 20, 2021, United Nations, accessed February 12, 2022, https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/publication/un-desa-policy-brief-108-trust-in-public-institutions-trends-and-implications-for-economic-security//.

- Ibid.

- Chandler Good Government Index, “Advisory Panel”, accessed February 11, 2022, https://chandlergovernmentindex.com/advisory-panel/.

- Chandler Good Government Index, “The Chandler Good Government Index 2022”, accessed April 29, 2022.