Growing from Clusters to Ecosystems

Digital Edition Issue 07, Sept 2021

In his 1996 Harvard Business Review article entitled “Clusters and the New Economics of Competition”,1 Michael Porter argued that well-established clusters of related firms, institutions and skilled workers enjoy an enduring competitive advantage through the concentration of factor endowments and the rivalry among them. For decades, cluster thinking has influenced growth strategies and location decisions. In recent years, however, an “ecosystem” concept has emerged.2 This updates cluster theory in three key ways.3

First, ecosystems are not defined by traditional industry boundaries. Innovation and competition emerge from the periphery or outside the industry and grow through network effects and webs of complementary products that connect and entrench consumers. Second, ecosystems are not limited by factor endowments and their control, but are fostered by creating abundance, such as through data—the value of which multiplies with the number of nodes (Metcalfe’s Law).4 Third, ecosystems do not require geographical proximity. This is salient as it points to ecosystems as a strategy for growth, particularly in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic which has driven remote working and the diversification of supply chains.

Ecosystems are not defined by traditional industry boundaries. Innovation and competition emerge from the periphery or outside the industry.

Analysis by Reeves et al. on 57 ecosystems in 11 sectors across geographies has found that only 15% of firms (including the likes of Microsoft Windows and Amazon) sustained a dominant share for more than 20 years.5 Successful ecosystems,6 such as the ones on which businesses like Netflix7 and ARM8 are based, have a compelling use case, a strong user base and partners from a diversity of industries and countries. Ecosystems have low barriers to entry and a modular architecture to easily mix and match components to generate more value together. They are held together by a benign orchestrator who is willing to share the bulk of the value to gain scale and speed. They tap present capabilities (“Exploit”) while constantly learning, evolving, and developing new capabilities and partners (“Explore”).9 Like the iPhone App Store, they are built on sound governance choices regarding access and membership to differentiate roles and motivate partners within the ecosystem.10 They share a common roadmap to coordinate complementary investments.

From Centralised Clusters to Dispersed Ecosystems

Traditionally, the Economic Development Board’s cluster development strategy for Singapore has aimed to concentrate and populate entire value chains in a physical location: such as Jurong Island for the chemical industry, Biopolis for the biomedical sciences, or the wafer fabrication parks for semiconductor manufacturing.

With greater remote working and diversification of supply chains, we may have to update our playbook to reap more value from geographically dispersed ecosystems (rather than geographically concentrated clusters). This may for instance involve identifying and anchoring one or more firms that serve key roles as orchestrators for their sector, or which make keystone contributions to their industrial ecosystem.

What determines whether a firm does well in an ecosystem? Williamson and Meyer say firms must make a unique “keystone contribution” which creates value for customers as well as establishes a “tollgate” to capture a reasonable amount of value.11 This view essentially extends the lenses of resources and capabilities as well as competitive strategy: firms succeed through rare resources and bargaining power. Drawing from the analogy of the ancient Battle of Thermopylae,12 in which several thousand Greek soldiers held off 100,000 Persian soldiers by focusing their resources to control a narrow pass, Hannah and Eisenhardt’s inductive study of the US residential solar market suggests that in nascent ecosystems, entrants create value by innovating at the bottleneck and freeing the ecosystem of its resource constraints (e.g., consumer finance), then actively cooperating with partners to invest in and improve complementary components, even if it means capturing less value.13

Successful ecosystems have a compelling use case, a strong user base and partners from a diversity of industries and countries.

To sustain the support of its partners, the ecosystem orchestrator must maintain an appropriate balance between value creation and value capture. Amazon’s dual roles as operator of the marketplace and a seller in that same marketplace is a negative example: its access to third party sellers’ data and information give it an unfair advantage over “competing” products on its platform.14 The growing concern about unfair competition such as this has prompted a major review of antitrust regulations to try to curb the dominance of Big Tech.15

Trust is an important prerequisite to cooperation, particularly in situations where interests conflict. Recent research shows that some aspects of trust, namely ability and reliability , can be built through online collaboration based on professional reputations and task competence.16 But what’s missing is benevolence (the belief that partners will resist the temptation of opportunistic behaviour and harming others for personal gains) which can only be sensed through face-to-face interaction.

Crisis presents decision makers with a severe test: do they continue to demonstrate benevolence when difficult trade-offs must be made? In 2020, when the COVID-19 infection cases in migrant worker dormitories swelled to nearly overwhelming proportions, Singapore stayed true to the principle of global humanity and determined to take care of these migrant fellow residents in our midst. That same combination of competence, benevolence and goodwill, built over decades of win-win partnerships with the global scientific and pharmaceutical community at the institutional and personal level, gave Singapore the network connections and access to make educated bets and secure the right COVID-19 vaccines for our people at speed to emerge from the crisis. As a small country, Singapore may not be the first to come up with an invention, but our cumulative investments and networks enable us to be plugged in to the best and most current around the world, and thereby have the “absorptive capacity”17 to recognise, assimilate and apply new knowledge.

Some aspects of trust, namely ability and reliability, can be built through online collaboration but benevolence can only be sensed through face-to-face interaction.

Collective human endeavour, whether in clusters or ecosystems, requires a spirit of cooperation, built on a sense of shared destiny and common cause. The enduring advantage of clusters may lie not in comparison and competitive rivalry, but in the environment of trust and cooperation they can foster.

- Michael E, Porter, “Clusters and the New Economics of Competition”, Harvard Business Review, November–December 1998, accessed August 18, 2021, https://hbr.org/1998/11/clusters-and-the-new-economics-of-competition.

- Eamonn Kelly, “Introduction: Business Ecosystems Come of Age”, Deloitte Insights, April 16, 2015, accessed July 26, 2021, https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/focus/business-trends/2015/business-ecosystems-come-of-age-business-trends.html.

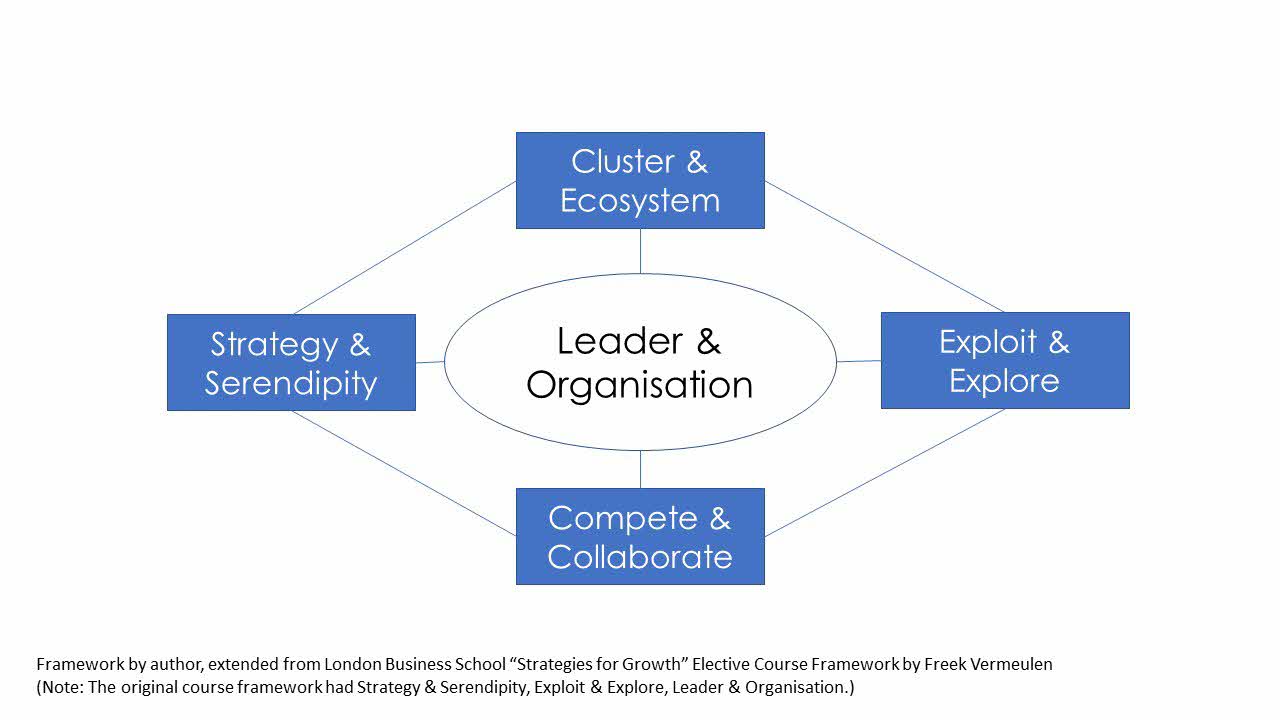

- The following diagram was developed by the author, extending the course framework for the London Business School’s “Strategies for Growth” Elective. Freek Vermeulen (n.d.). Strategies for Growth: Making Strategy Happen [PowerPoint slides].

- Metcalfe's law states that the value of a network is proportional to the square of the number of users or nodes in the network (n2). See “ETS Profiles: Dr. Bob Metcalfe”, video posted December 19, 2018, accessed July 26, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pPXCuf7xLsM.

- Martin Reeves, Hen Lotan, Julie Legrand, and Michael G. Jacobides,. “How Business Ecosystems Rise (and Often Fall)”, MIT Sloan Management Review, July 30, 2019, accessed July 26, 2021, https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/how-business-ecosystems-rise-and-often-fall/.

- Michael G. Jacobides, Nikolaus Lang, and Konrad van Szczepanski, “What Does a Successful Digital Ecosystem Look Like?” June 26, 2019, accessed July 26, 2021, https://www.bcg.com/publications/2019/what-does-successful-digital-ecosystem-look-like.

- Iryna, “Netflix: The Rise of a New Online Streaming Platform Universe”, Digital Innovation and Transformation MBA Student Perspectives, March 4, 2018, accessed July 26, 2021, https://digital.hbs.edu/platform-digit/submission/netflix-the-rise-of-a-new-online-streaming-platform-universe/.

- Unlike the vertically integrated model of Intel, ARM deploys a “design and license” business model involving ecosystem partners, to deliver low power computing at significantly reduced developing cost. Tanmoy Sen, “Platform Ecosystem, ARM’s Answer to Intel’s Dominance”, 2014, accessed August 13, 2021, https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/111290/1002855245-MIT.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Michael L. Tushman, Wendy K. Smith, and Andy Binns, “The Ambidextrous CEO”, Harvard Business Review, June 2011, accessed August 18, 2021, https://hbr.org/2019/06/the-ambidextrous-ceo. Tushman and Smith describe ambidexterity as the ability to balance core business (“Exploit” in the framework above) and new businesses and markets (“Explore”). Striking a balance between Exploit and Explore is key to Growth. This requires leaders and leadership teams to hold tension at the top (because innovation would lose out otherwise) and in being able to live with inconsistencies and conflicting strategic agendas (sometimes even supporting innovation units that may appear to cannibalise core businesses).

- Michael G. Jacobides, “In the Ecosystem Economy, What’s Your Strategy?” Harvard Business Review, September–October 2019, accessed July 26, 2021, https://hbr.org/2019/09/in-the-ecosystem-economy-whats-your-strategy.

- Peter Williamson and Arnoud De Meyer, “How to Monetize a Business Ecosystem”, Harvard Business Review September 30, 2019, accessed July 26, 2021, https://hbr.org/2019/09/how-to-monetize-a-business-ecosystem.

- David Clough, “Reflections on Hannah and Eisenhart’s ‘How Firms Navigate Cooperation and Competition in Nascent Ecosystems’: Exploring Bottlenecks as a Central Concept in Innovation Ecosystem Theory”, Strategic Management Society Blog, June 21, 2018, accessed July 26, 2021, https://strategicmanagementsociety.wordpress.com/2018/06/21/reflections-on-hannah-and-eisenhardts-how-firms-navigate-cooperation-and-competition-in-nascent-ecosystems-exploring-bottlenecks-as-a-central-concept-in-innovation-ecosyste/.

- Douglas P. Hannah and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt, “How Firms Navigate Cooperation and Competition in Nascent Ecosystems”, Strategic Management Journal, working paper, December 12, 2017, accessed July 26, 2021, https://marriott.byu.edu/upload/event/event_368/_doc/Hannah%20Ecosystems.pdf.

- Jerrold Nadler, Chairman, Committee on the Judiciary and David N. Cicilline, Chairman, Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial and Administrative Law, “Investigation of Competition in Digital Markets”, 2020, accessed August 20, 2021, https://judiciary.house.gov/uploadedfiles/competition_in_digital_markets.pdf?utm_campaign=4493-519.

- Review is necessary as current antitrust doctrine examines impacts on consumer welfare (not businesses) based on short-term direct price effects and underappreciates how network effects may prove anticompetitive. Lina Khan, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox”, Yale Law Journal, 2017, accessed August 20, 2021, https://www.yalelawjournal.org/pdf/e.710.Khan.805_zuvfyyeh.pdf.

- Jasper De Vreis, S. Van Bommel, and Karin Peters, “Trust at a Distance—Trust in Online Communication in Environmental and Global Health Research Projects.”, Sustainability 10, no. 11 (2018): 4005.

- David J. Teece, “Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Microfoundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance”, Strategic Management Journal 28, no. 13 (December 2007).

</em>