Using Behavioural Insights to Increase Charitable Donations

ETHOS Digital Issue 03, Sep 2018

Introduction

Voluntary Welfare Organisations (VWOs) are non-profit entities that rely on government grants, as well as their own fundraising, to provide a wide range of social services and basic welfare provisions—particularly to disadvantaged and vulnerable groups. In Singapore, some 449 VWOs were registered with the National Council of Social Service in 2015.1

Donations from corporations and individuals are key in keeping VWOs functioning. The Singapore Government has actively encouraged charitable giving through generous tax deduction rates. In his Budget Speech for 2015, Singapore’s Golden Jubilee year, Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam emphasised the importance of “Fostering a Spirit of Giving” within Singaporean society. To encourage donations that year, the tax deduction rate on all donations was increased from 250% to 300%. Charitable donations hit a 17-year peak in 2015, resulting in S$1.4 billion in tax deductible donations.

However, VWOs cannot rely on such temporary boosts in the long term. In addition, many VWOs tend to receive donations from a limited pool of regular donors, which puts them at risk, especially during periods of recession. More effective fundraising efforts to increase the amount raised and widen the pool of donors would help VWOs to be more financially stable.

In other countries, behavioural nudges have proved effective in fundraising and are widely used by charitable organisations to encourage more donors to contribute (see box story). Might such nudges be equally effective in Singapore, enabling more sustainable approaches to raise funds for needy causes here? A first-of-its-kind study was conducted by the Civil Service College in partnership with the Singapore After Care Association (SACA) to investigate this.

A range of established concepts in behavioural literature suggest how VWOs could nudge for more donations.

What Studies from Other Countries Reveal

A range of established concepts in behavioural literature suggest how VWOs could nudge for more donations.

- Reciprocity can be effective in fundraising. In a large-scale natural experiment with an international charity for children,1 pre-donation “thank you” postcards made by the children were sent out to potential donors along with the fundraising letter. One group received only one postcard and the other one received four postcards. A third group did not receive any postcard, so that that the results from the other two groups could be compared to the status-quo practice. Compared to this control group, those who received one postcard had a 17% higher rate of donation; those who received four postcards had a 75% higher rate of donation.

- Focusing on individual beneficiaries rather than total impact can also be highly effective. Loewenstein et al.2,3 found that telling people how many beneficiaries had been impacted yielded an average donation of $1.45, versus $2.34 when people were told of the struggles experienced by an individual beneficiary.

- Anchoring at low donation amounts such as adding the phrase “even a penny will help” when soliciting for door-to-door donations increased the rate of contribution from 29% to 50% in a field experiment by Cialdini and Schroeder.4 More importantly, this did not make a difference in the size of the average contributions, which is a common concern with anchoring donations at small amounts.

- Social norms, such as telling students the percentage of students who had donated (either in the past or currently), have resulted in higher donation rates compared to not doing so.5

- Offering a lottery In a 2006 study, donors gave approximately 50% more when they were told that their donation made them eligible for a prize, compared to those who were not.6 This result was largely driven by increased participation rates among male donors. These donors also continued to give more the next time they were asked for a donation.

Notes

- A. Falk, “Gift Exchange in the Field”, Econometrica 75 (2007): 1501–11.

- G. Loewenstein and D. Small, “Helping a Victim or Helping the Victim: Altruism and identifiability”, Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 26 (2003): 5–16.

- G. Loewenstein, D. Small and P. Slovic, “Sympathy and Callousness: The Impact of Deliberative Thought on Donations to Identifiable and Statistical Victims”, Organisational Behavioural and Human Decision Processes 102 (2007):143–53.

- R. Cialdini and D. Schroeder, “Increasing Compliance by Legitimizing Paltry Contributions: When Even a Penny Helps”, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 34 (1976): 599–604.

- B. Frey and S. Meier, “Social Comparisons and Pro-Social Behavior: Testing ‘Conditional Cooperation’ in a Field Experiment”, The American Economic Review 94 (2004): 1717–22.

- C. Landry, et al., “Toward an Understanding of the Economics of Charity: Evidence from a Field Experiment”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 121 (2006): 747–82.

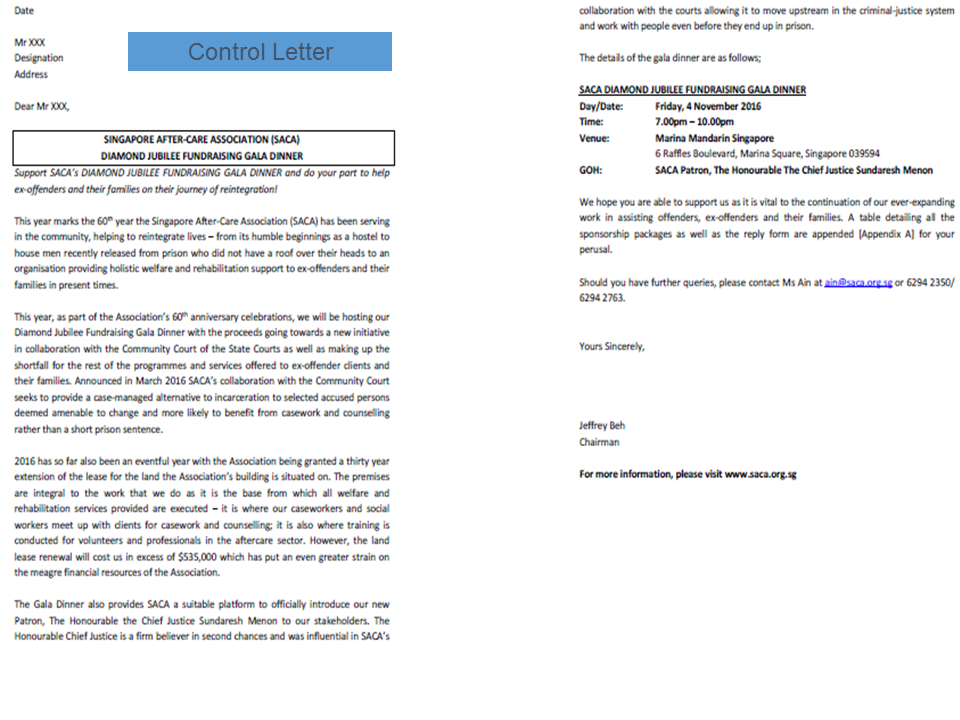

Partnering SACA in a Randomised Controlled Trial

SACA is an aftercare agency providing welfare and rehabilitation services for discharged offenders and their families.2 It receives approximately 50% of its funding from the government and relies on a small group of regular donors for the rest. This group consists of 30 to 40 corporations that donate significant sums of money (totalling about $70,000 in 2015) every year. Contributions from individual donors are minimal, both in numbers and donation amounts.

SACA was keen to find new ways to expand its donor base. Seeing an opportunity to do this at its 60th anniversary fundraising dinner in 2016, SACA’s management agreed to test out different appeal letters to corporations, inviting them contribute by “buying tables” for the Gala Dinner.

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) was used to test the effectiveness of the different appeal letters compared to the usual letter that was sent out for previous fundraising events. The testing letters took into account SACA’s privacy policy to protect their beneficiaries and families. This meant that images or personal stories of beneficiaries could not be included. In addition, leveraging social norms was not tenable because the number of current donors as a percentage of SACA’s total email outreach was small. Finally, as the outreach was for corporate donors, a lottery or small tokens of appreciation were not deemed appropriate either.

Eventually, we decided to test two sets of new letters. Both were edited for a more succinct read (see “Making Letters More Succinct and Easier to Read”). Each set of these “treatment” letters incorporated one of the following interventions:

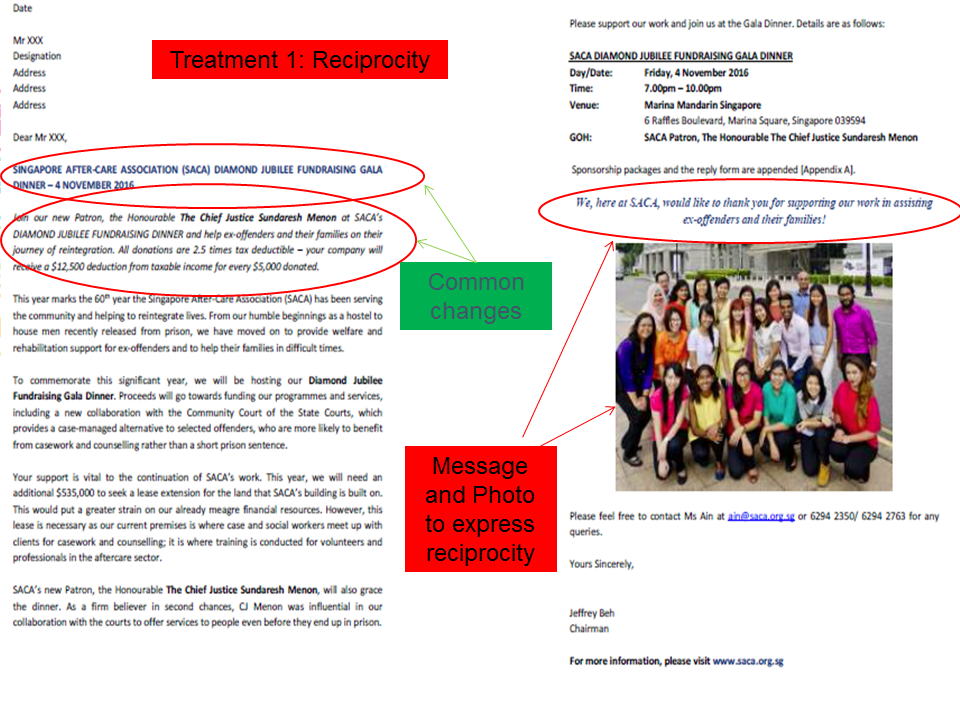

A picture of SACA staff was used to thank the potential donors for their contributions and support, along with a sign-off message: “We, here at SACA, would like to thank you for supporting our work in assisting ex-offenders and their families!"

Reciprocity (in a modified form)

A picture of SACA staff was used to thank the potential donors for their contributions and support, along with a sign-off message: “We, here at SACA, would like to thank you for supporting our work in assisting ex-offenders and their families!"

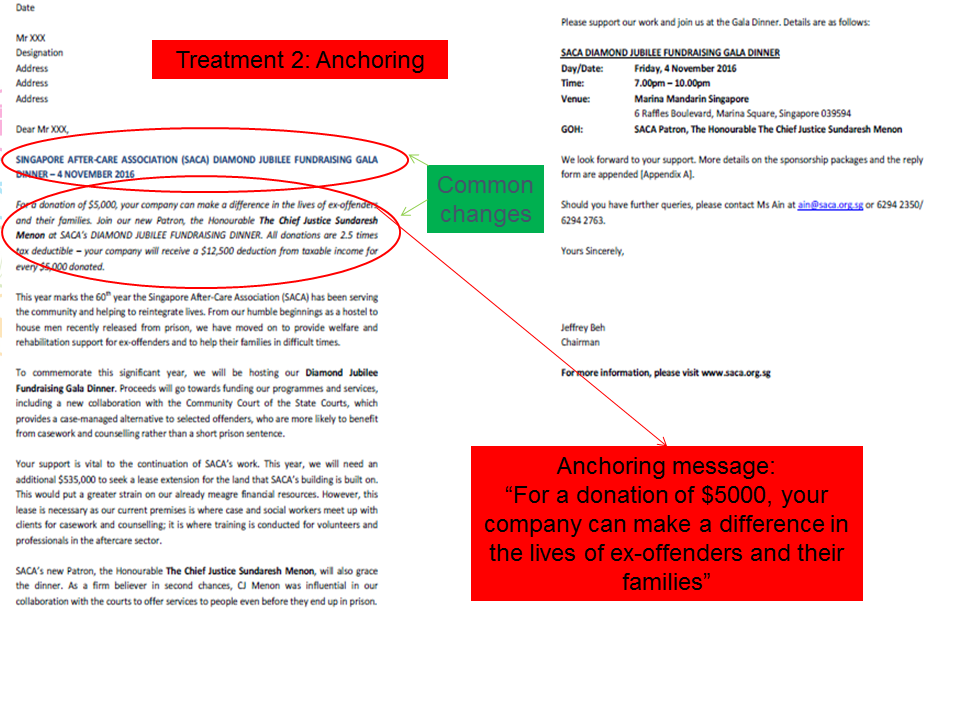

The anchor donation amount was set at $5,000 (smallest sponsorship option per table). The first line of the letter read: “For a donation of $5,000, your company can make a difference in the lives of ex-offenders and their families.”

Anchoring

The anchor donation amount was set at $5,000 (smallest sponsorship option per table). The first line of the letter read: “For a donation of $5,000, your company can make a difference in the lives of ex-offenders and their families.”

Three sets of appeal letters were sent out in late July 2016, about 3 months prior to the Gala on 4 November 2016, to a total of 599 corporate organisations:

- 199 (control – the usual appeal letter template used in previous fundraisers)

- 200 (new – reciprocity letter)

- 200 (new – anchoring letter)

Corporations which received the appeal letters were either cold calls, or those who were on SACA’s mailing list but had either not donated before or donated in the last 3 to 4 years. Each were randomly chosen to receive 1 set of the appeal letters. Regular donors were excluded from the outreach as SACA had already engaged them at a separate fundraising event earlier in the year.

Other than testing out the specific behavioural concepts of reciprocity and anchoring, both sets of treatment letters were made more readable, by:

- Condensing the history of the organisation;

- Putting important information upfront, such as the date of the Gala Dinner and tax deduction rate, as well as highlighting the new Patron, the Honourable Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon;

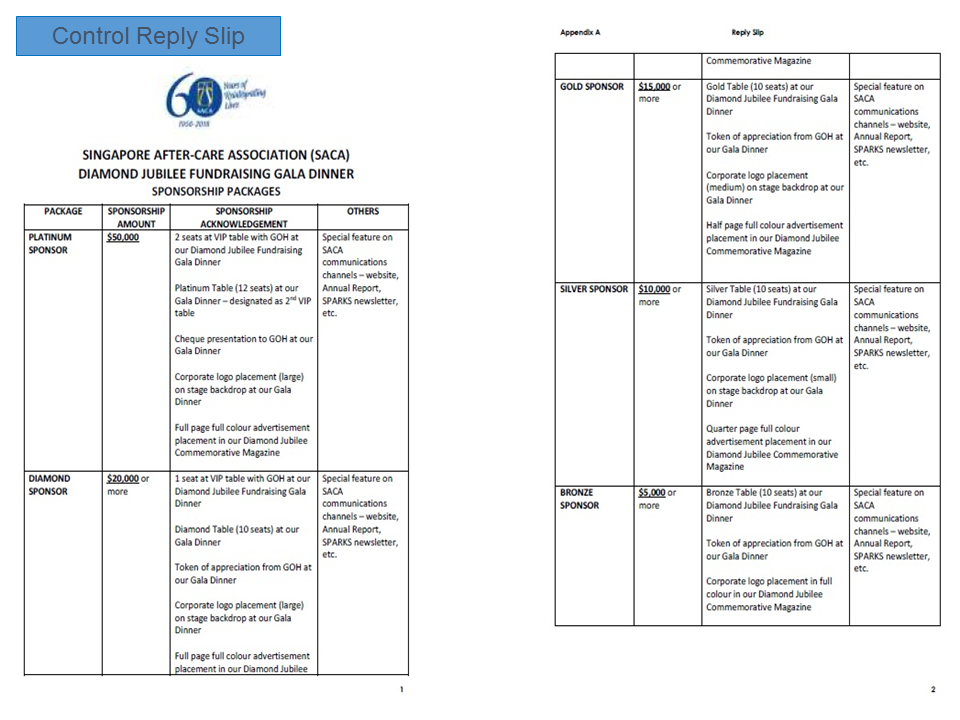

- Reducing the reply slips sent along with the treatment letters from two pages to one, with a clear call for action stating: “Please choose 1 of the sponsorship packages to support SACA”.

Making Letters More Succinct and Easier to Read

Other than testing out the specific behavioural concepts of reciprocity and anchoring, both sets of treatment letters were made more readable, by:

- Condensing the history of the organisation;

- Putting important information upfront, such as the date of the Gala Dinner and tax deduction rate, as well as highlighting the new Patron, the Honourable Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon;

- Reducing the reply slips sent along with the treatment letters from two pages to one, with a clear call for action stating: “Please choose 1 of the sponsorship packages to support SACA”.

Results

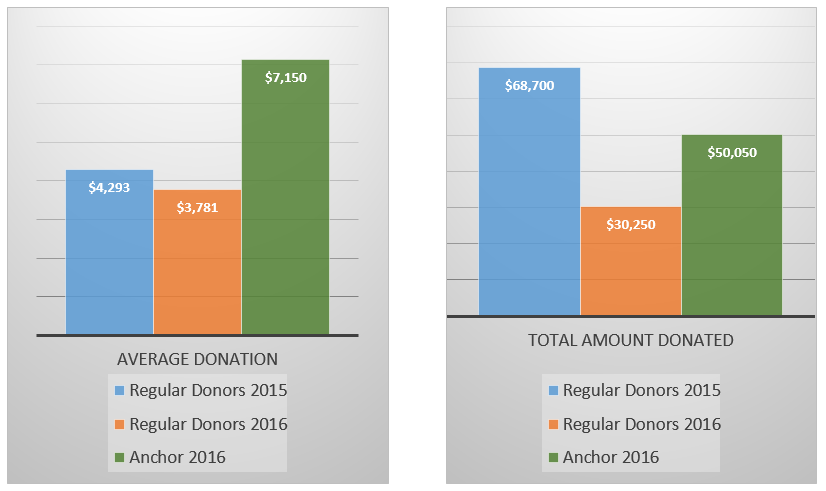

In context, 2016 was not a good year for charities. The Straits Times reported an overall dip in charitable donations,3 which was also experienced by SACA. This was evident at SACA’s fundraising event for regular donors earlier in the year, where donations only reached $30,000 as compared to about $70,000 from the same group in 2015.

This general low yield across charities for the year explains the low rate of return for the trial. Despite this, the benefit of running the trial was that results between donors who received different letters could still be compared, yielding insights on what could possibly encourage donors to contribute more. The "anchoring" appeal was found to be the most effective. We also found that:

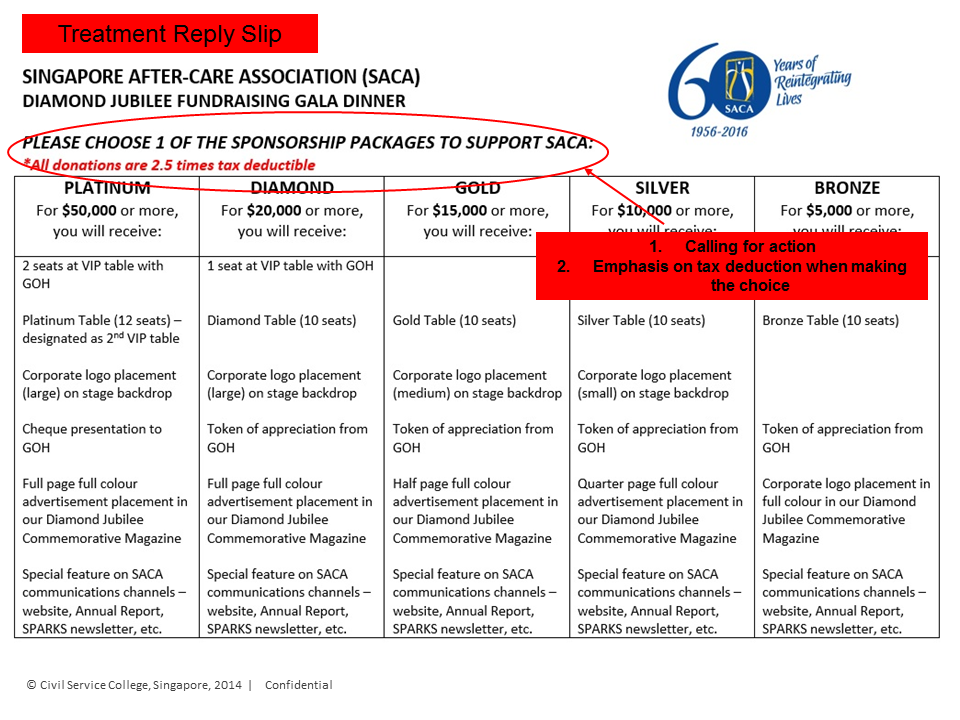

- Anchoring was effective in improving both the donation amount as well as donor numbers for the fundraising dinner.4 Of the total of $50,750 collected, 98% came from the "Anchoring" group ($50,050, 7 donors). The control and "Reciprocity" groups yielded $500 and $200 respectively (each group had 1 donor).

- Anchoring also brought about more awareness on SACA’s work. While some corporates that received the "Anchoring" letter did not donate, they sent a reply that acknowledged SACA’s cause and stated reasons for not being able to donate (mostly budgetary constraints). Such responses were valued by SACA as it signalled interest and possibilities for eliciting future donations.

- Anchoring did not depress donation amounts. While the anchor amount was $5,000, the average donation from the anchoring group was $7,150, with 43% of the donations at $10,000 and above. This assuaged concerns that anchoring might lower the average size of contributions to the anchor amount of $5,000.

- Diversification beyond regular donors. While the number of donors from the anchoring group was similar to SACA’s regular donors group (about 7 to 8 each), the anchoring group donated almost $20,000 more than regular donors in 2016. In addition, average donations from the "Anchoring" group were almost double that of regular donors in 2016, and was $3,000 more than the average donation from regular donors in 2015.

What We Learnt

- Context Matters

Many charities in Singapore rely on small groups of regular corporate donors, unlike many overseas charities which rely heavily on individual donors. As in the case of SACA, this precluded the applicability of many nudges in the literature. The trial had to be designed with the corporate donor profile and behaviour in mind. - Importance of a Control Group

If the study had been done to solely compare donation levels before and after the experiment, the conclusion would have been that both reciprocity and anchoring were ineffective, simply because the overall donations to charities in 2016 were much lower than in previous years. However, an RCT (having a concurrent control group) allowed the elimination of external factors such as the economic outlook and change in business priorities post-2015 (Jubilee Year). Insights on the effects of anchoring and reciprocity could then be assessed more accurately. - Working around Practical Challenges

The main challenges were to ensure a big enough sample size, and to work around the constraints of SACA as an organisation. “Cold calls” had to be made in order to reach 200 letters per treatment. Nudges also had to take into account the privacy of the beneficiaries and their families in the context of SACA’s cause. - Low Cost, High Gains

This RCT proved that nudges can result in large gains at low costs to charities. Anchoring resulted in $50,000 donations for SACA just by redesigning the appeal letters.

Conclusion

Encouraged by the results of the trial, SACA has since adopted the new letter and reply slip design from the "Anchoring" letter group for its fundraising appeals. This experiment has been shared with relevant social agencies who have also found it very useful. Through this project, we hope to illustrate to VWOs and social agencies that RCTs are not necessarily complicated or expensive yet can yield very insightful and rigorous results that can improve their everyday operations.

NOTES

- Isabel Sim, Corinne Ghoh, Alfred Loh and Marcus Chiu, “The Social Service Sector in Singapore—an Exploratory Study on the Financial Characteristics of Institutions of a Public Character (IPCs) in the Social Service Sector”, National University of Singapore, October 2015, accessed 10 January 2016, https://www.fas.nus.edu.sg/swk/doc/CSDA%20An%20Exploratory%20Study%20on%20the%20Financial%20Characteristics%20of%20IPCs%20in%20the%20Social%20Service%20Sector.pdf.

- For more information on SACA, please visit: www.saca.org.sg.

- S. Yuen and Kok Xing Hui, “Some Charities Seeing Dip In Donations”, The Straits Times, 27 November 2016, accessed 1 March 2017, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/some-charities-seeing-dip-in-donations.

- The results were statistically significant at p=0.05 using two-tailed test, which means that there is only 5% chance that the results between the control and anchoring groups differed only by chance.