Partnering with the Public in the War on Diabetes

ETHOS Digital Issue 03, Sep 2018

Singapore’s fight against diabetes is a multifaceted issue that was raised to national importance by the Prime Minister in his 2017 National Day Rally speech. The Ministry of Health (MOH) has been exploring ways to involve the public in developing community-based solutions to address this complex issue which involves many stakeholders across different sectors in society.

One approach that MOH has employed is the Citizens’ Jury methodology. Citizens are given access to resources (material, subject matter experts, caregivers of people with diabetes and people with diabetes) to help them better understand the issue at hand, so they can come up with community-based proposals that may augment MOH’s efforts to fight diabetes. Unlike more familiar public engagement methods such as focus group discussions, a Citizens’ Jury calls for ongoing involvement throughout the engagement period, and provides for ground-up initiatives and co-delivery of solutions after the initial engagement phase.

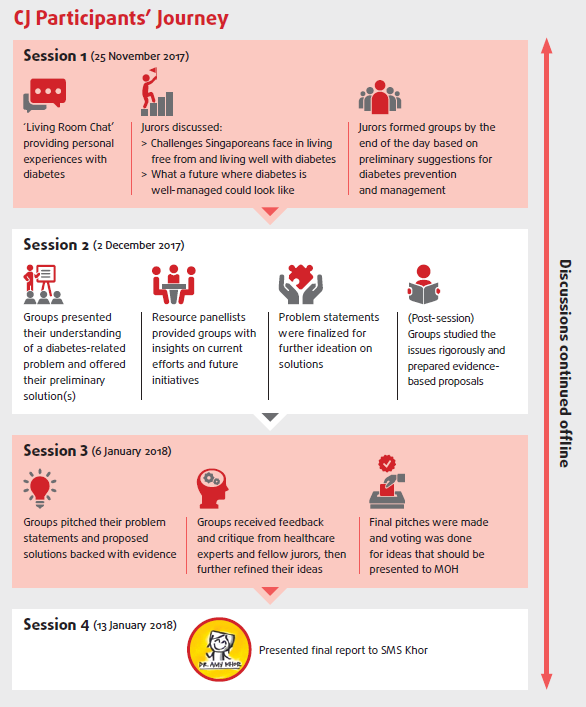

This is the first time that a Citizens’ Jury has been conducted in Singapore. Between 25th November and 13th January 2018, 76 individuals from different walks of life were selected to deliberate, discuss and achieve consensus on how we can combat diabetes in Singapore. The participants were diverse in terms of their age, education and racial background. This diversity meant that discussions were informed by different personalities, ideas and points of contention.

A Citizens’ Jury calls for ongoing involvement, and provides for ground-up initiatives and co-delivery of solutions after the initial engagement phase.

Key Learning Points

There were three main insights from this exercise:

Learning point # 1

Participants came to appreciate that developing community-centric solutions were more complex than they had previously thought, and that time was needed to formulate sound recommendations.

Better appreciation of the complexities in policymaking

Very early on in the process, participants were provided with information on the issue of diabetes in Singapore. Apart from analysing the data, they also heard from a range of other passionate participants, with at times contradictory points of view. They soon realised that solving the problem of diabetes was not as easy as it first seemed; there were tradeoffs to be considered. For example, when one group proposed to install water coolers at all hawker centres, others in the group brought up economic considerations such as the livelihoods of drink sellers.

After the Citizens’ Jury exercise, 40% of the participants indicated that there was insufficient time for the process. Some suggested that there should be one more session due to the amount of work (research, pitch and report writing) that had to be done. The seven-week duration was meant to balance participants’ other commitments with ample time for participants to deep dive into the issues, analyse existing literature and efforts, and provide fresh insights in their proposals. Of the participants, 86% indicated that they came to better appreciate the challenges involved in policymaking, particularly the need to balancing competing needs and different viewpoints when developing community-based solutions.

Participants came to appreciate that developing community-centric solutions were complex, and that time was needed to formulate sound recommendations.

Key enabler: Step-by-step process

The Citizens’ Jury process was intentionally designed such that there were milestones to be reached at each session. For example, at the end of the first session, the participants had to identify the broad topics they were keen to study. This was followed up with specific questions that required them to think more deeply about the issues, such as why they mattered, and what was currently being done locally and globally. This allowed participants to study the topic, analyse local and global data and gather feedback before laying out all the considerations and deciding the best way forward for the community. These were applied throughout the seven-week process.

Learning point #2

The Government found affirmation that many citizens are indeed keen and ready to collaborate in or co-create community-based solutions for social issues of concern to Singaporeans. More opportunities should be provided for such deliberative capabilities to be nurtured further.

Highly involved process

Given their heavy personal investment in the topic, participants came to the engagement with ideas on how they could solve the problem of diabetes. They studied the materials, engaged each other and subject matter experts to better understand the issues, and developed surveys to gather data from the public before developing community-based solutions. The facilitation team also devoted time to support the participants throughout the process. This included prompting them to use empirical or credible sources to substantiate their work, to consider multiple perspectives, and to develop feasible proposals that the general public would be keen in adopting.

Sustained involvement, post Citizens’ Jury

After the process, 90% of participants expressed their desire to be more actively involved in diabetes prevention and management initiatives, and wanted to inspire their families and friends to do the same. Participants also continue to engage one another through Whatsapp, and the Facebook groups remain active as they continue to share and discuss relevant articles and issues. Some participants have also implemented their ideas (e.g., healthier cooking classes at community centres) while others have initiated discussions with community partners (such as the South East CDC) to pilot their ideas.

The participants’ positive involvement and feedback offers scope for the Public Service to engage citizens and involve them more purposefully through a variety of modes, including post-engagement opportunities and resources for follow-up activities. Nurturing active citizenry surely takes time but we should take bold steps to facilitate it.

Many citizens are keen to collaborate in or co-create community-based solutions for social issues of concern to Singaporeans.

Key enabler: Supportive partners

As part of the process, MOH reached out to 21 individuals across different organisations to serve as resource persons. These included academics, practitioners and people who had relevant experience. MOH conducted pre-session briefing sessions with the resource persons to equip them with the progress of discussions, as they were entering the process at different points over its seven-week duration. Apart from being a resource to participants, they also gave constructive feedback on the interim ideas being developed and shared personal stories to inspire participants. Some of these partners also provided platforms to prototype ideas in a live setting. For example, ActiveSG representatives invited participants to the Active Health Lab so that the group could test some of their ideas of how to get Singaporeans to adopt a more active lifestyle. South East CDC welcomed other groups to test out ideas such as healthier cooking classes. This meant that that engagement was extended to a larger space of experimentation which could provide immediate feedback on whether solutions were feasible, and how they were received.

Learning point #3

For both parties, the Citizens’ Jury was a ground-breaking experience, an exercise in trust-building, and a new way to make policy in Singapore.

Creating a safe space

The participants were initially sceptical about the credibility of the Citizens’ Jury process, because this had never been done before. However, it was clear by the end of the process that the participants felt it was a safe environment in which they could fully and sincerely engage on multiple issues, with plenty of mutual support. For example:

- Three participants decided to form a social media team and took responsibility to create and manage a closed Facebook page. Participants continue to exchange and share ideas on this platform, post Citizens’ Jury.

- In the lead-up to the final session, participants volunteered and formed an organising committee with various roles and responsibilities to host the presentation of the report to MOH. These roles included emceeing, ushering, report writing, guests management, and presentation.

The participants wrote and compiled their report independently, with no involvement from MOH during writing or submission.

Closing the loop

In keeping with the commitment to respond to their report within three months, a session was organised to present MOH’s response to the participants within the stipulated period. Senior Minister of State Amy Khor and senior management from various Ministries were present at the session to deliver and explain MOH’s response.

Key enablers: MOH facilitators

Sixteen dedicated volunteer facilitators from MOH Facilitators’ Network (FaciNet) supported the entire process. Their ability to navigate the uncertainties, coupled with their agility provided a strong base of support for participants. Given that the Citizens’ Jury was participant-driven, the facilitators were required to gently balance giving participants the space to explore with being more interventionist when they needed to move the process along. A common sight at the Citizens’ Jury that is different from the traditional focus group discussions, is that the participants are the ones leading the discussions and penning down the group’s thoughts on the flipchart.

Nurturing active citizenry surely takes time but we should take bold steps to facilitate it.

Reflections: What Might Have Made It Even More Effective?

Clarity on extent of participant involvement

At the point of registration, participants were informed about the scope of the engagement, and that they needed to attend four sessions. However, participants realised that they also had to work on the issues between sessions, given the intensity of the engagement. On reflection, MOH could have shared more about the deliverables for the engagement: which included research in between engagement sessions, pitching of ideas, and compiling a report. Such details would have helped participants be fully aware of the commitment expected of them. In this instance, the participants were fortunately willing to step up their efforts to match the demands of the Citizens’ Jury process.

Better understanding of efforts to fight diabetes

The Citizens’ Jury Secretariat prepared an information booklet for all participants to ensure everyone was equipped with basic knowledge of existing efforts to combat diabetes. It quickly became clear that despite public communication efforts, awareness amongst participants remained low. On reflection, we could have set aside more time to brief participants on the issue and the competing considerations from the start.

Is Conducting a Citizens’ Jury the New Buzzword for Public Engagement?

The Citizens’ Jury is one of many engagement tools. As with all other methodologies, it has the potential for wider adoption but may not be applicable to all issues, and is furthermore resource intensive. Nevertheless, the principles of this process can be adopted to further strengthen and nurture active citizenry, by working towards well-informed citizens, clear commitment to follow up, and empowering citizens to contribute solutions to issues of importance to the community, within a safe space.

CJ Participants' Journey and Video Highlights