Fertility Rebound in the OECD: Insights for Singapore

ETHOS Digital Issue 03, Sep 2018

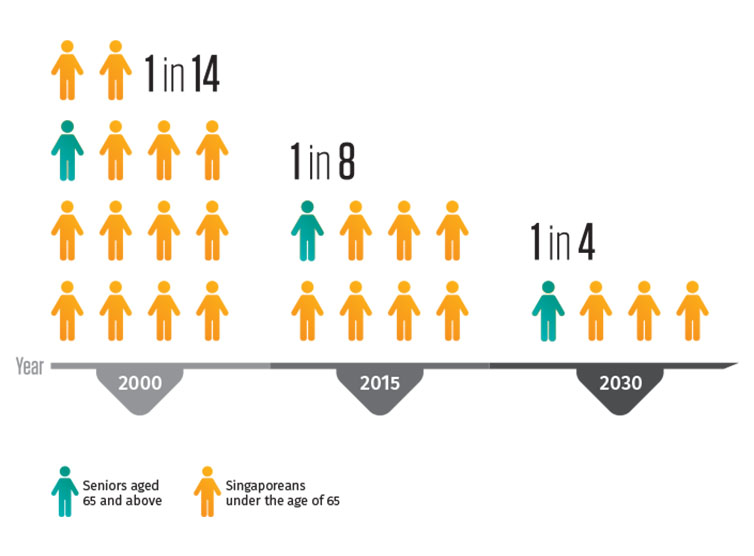

Singapore faces significant demographic challenges. Since 1976, the country’s resident total fertility rate (TFR) has been below the replacement level of 2.1.1 In 2017, the resident TFR stood at 1.16 births per female.2 With our current low fertility rates and increasing life expectancy, by 2030, we can expect one in four Singaporeans to be aged 65 and above.3

Figure 1. Impact of Singapore’s current low fertility rates and increasing life expectancy

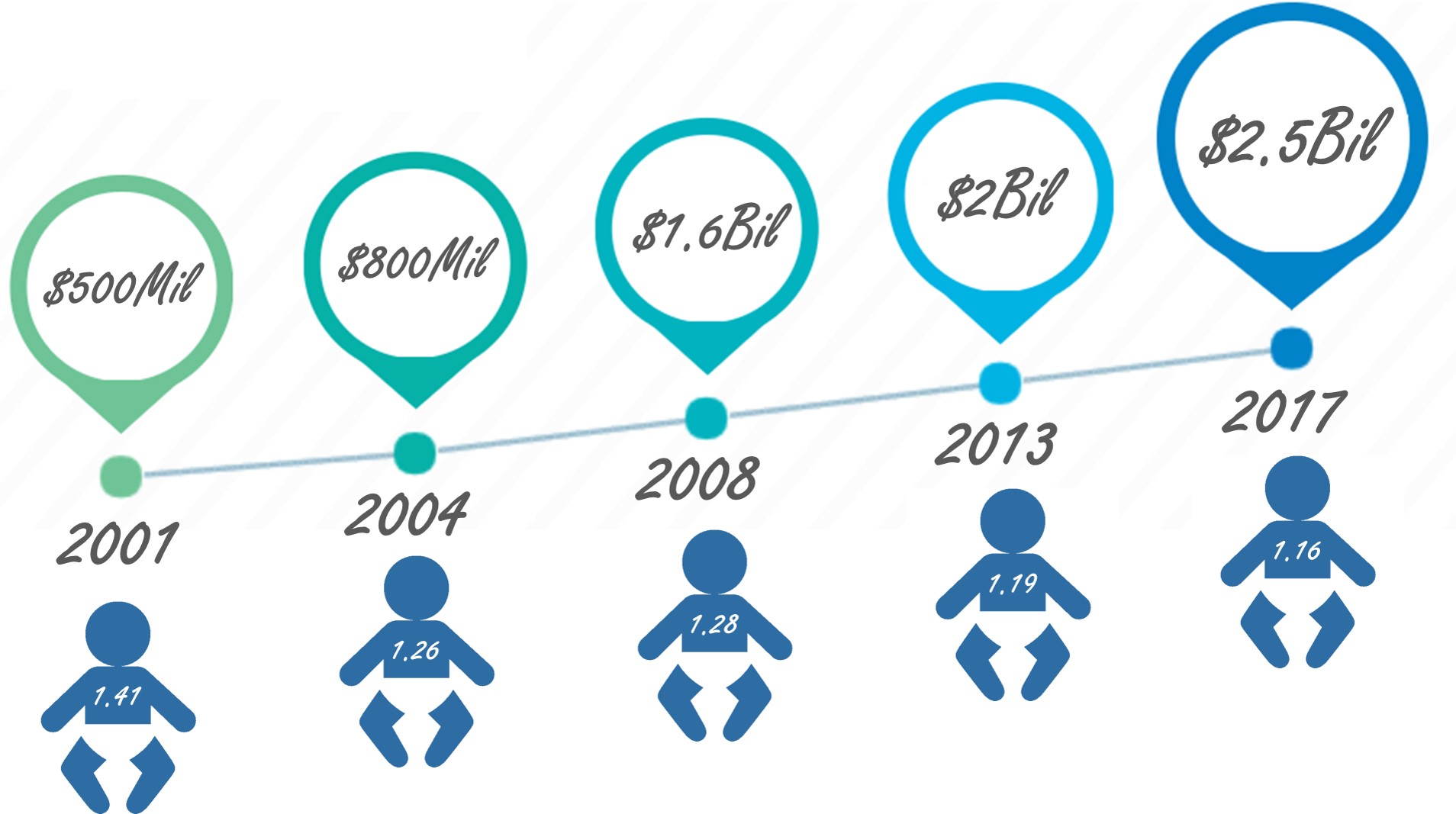

To forge a strong and cohesive national identity and maintain a vibrant economy, it is important that Singapore sustains a stable citizen population over the long term. Raising TFR therefore remains a national priority.4 In 2001, the Government introduced the Marriage and Parenthood (M&P) Package to encourage and support Singaporeans’ decision to marry and have kids. This package has been progressively and significantly enhanced over the years: between 2001 and 2017, annual budget commitments to the M&P Package has more than quadrupled from $500 million to $2.5 billion.5

Despite these efforts, Singapore’s TFR continues to decline (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Annual budget commitment to M&P package and resident TFR, 2001–20176

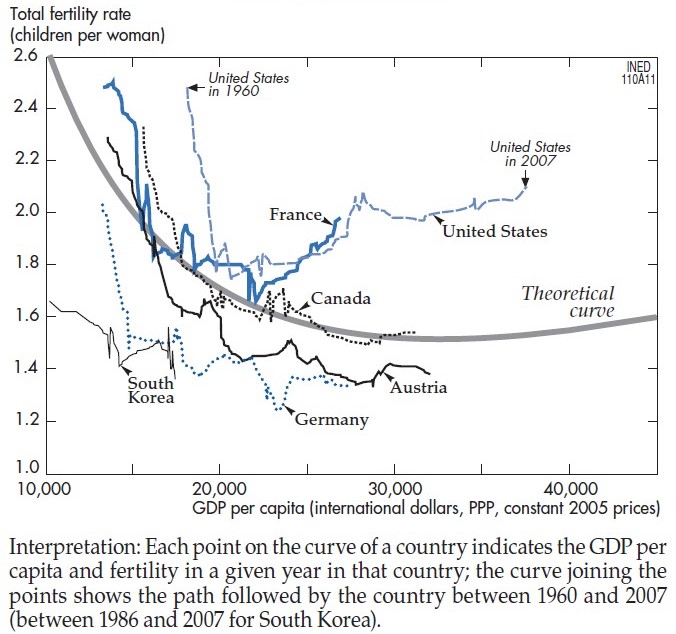

These demographic challenges are not unique to Singapore. The TFRs in many OECD countries have also declined rapidly in a period marked by economic growth. In the last decade, however, a trend reversal has been observed: against the backdrop of continued economic development, the TFR in some OECD countries has rebounded. What caused this fertility rebound, and how might this be replicated in Singapore?

Understanding the Fertility Rebound

The fertility rebound can be understood as a changing relationship between economic growth and TFR. Studies have found an inverse J-shaped pattern of fertility along the process of economic development (see Figure 3) where, in economically advanced OECD countries, further economic advancement is likely to induce a fertility rebound. There are however still variations in TFR among countries with similar or even higher levels of GDP per capita.7

Figure 3. An inverse J-shaped curve emerges when TFR is plotted against GDP per capita (selected countries), 1960–20078

According to OECD Social Policy Analyst Dr Olivier Thevenon, cross-country variations in TFR can be attributed to institutional factors such as family policies. The fertility rebound was particularly significant in highly-developed countries such as Belgium, Denmark, France, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom (UK), where women’s participation in the labour market is also high.9 In these countries, family policies appear to strike a balance that is favourable to work-life reconciliation. In contrast, low fertility OECD countries show comparatively low female employment rates.

One key parameter underlying the fertility rebound is the availability of opportunities to combine work with family formation. Among other reasons, couples are less likely to have children if they have to choose between parenthood and their careers. In light of this, Singapore could be more deliberate and proactive in promoting work-life reconciliation, and there are compelling reasons to do so. Singapore continues to clock one of the highest hours worked in the world (with a weekly average of 45.6 paid hours worked per person), and this has real and significant implications for the resident TFR.10 Singapore can draw valuable insights from the OECD countries with regard to policy approaches that promote work-life reconciliation.

Couples are less likely to have children if they have to choose between parenthood and their careers.

Family Policies in OECD Countries

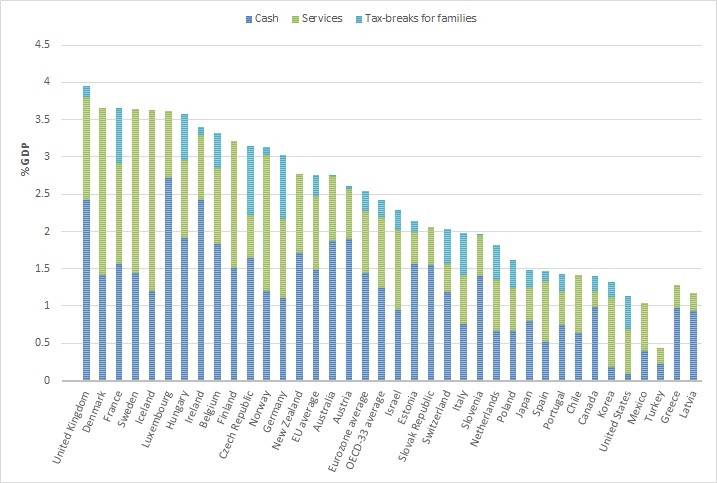

Family policies across the OECD have expanded alongside increases in public spending on family benefits as a proportion of GDP. By comparison, Singapore’s 0.6% GDP expenditure on family benefits is significantly lower than the OECD average of 2% GDP expenditure. However, spending among the OECD countries varies widely. Public spending on family benefits is above 3.5% of GDP in Denmark, France, Hungary, Sweden and the UK, whereas this figure stands below 1.5% of GDP in Japan, South Korea, Portugal, Spain, Turkey and the United States.11

There are also variations in the proportional amount each country spent on different types of family benefits, including cash benefits (e.g., family allowances, income support during parental leave), in-kind service provision (e.g., supports for Early Childhood Education and Care), and tax breaks (e.g., child tax credits and tax allowances for dependent children) (see Figure 4).12

Figure 4. Public spending on family benefits as a percentage of GDP, 201313

Arguably, this variation reflects two key differences across the OECD: first, the different allocation of roles in welfare provision among the family, state, and the market; and second, the different family policy models.

Policy models embody institutionalised relationships between policy objectives and policies. In most OECD countries, family policies are not introduced to solely address fertility concerns, but to prevent family poverty, foster female employment and improve gender equity, among other policy objectives. Different family policy models emerge as countries balance these policy objectives differently and deploy a diverse mix of family policies to achieve these aims.

Generally however, family policy models comprise three types of policies: (a) income support; (b) childcare services; and (c) leave entitlements.

In most OECD countries, family policies are not introduced to solely address fertility concerns, but also other policy objectives.

Income Support

Income support measures such as cash benefits and child-related tax benefits encourage parenthood by reducing the direct financial cost of raising children. Most OECD countries provide family benefits in the form of cash benefits. In 2009, cash benefits made up more than 40% of public spending in all but nine OECD countries.14 Spending on cash benefits include grants around childbirth (like that of Singapore’s Baby Bonus Scheme). It also includes regular and sustained payments over childhood, such as family allowances, child benefits or working family payments. Some OECD countries also include one-off benefits such as back-to-school-supplements or social grants for housing in these amounts. Cash benefits may vary by family size: in Belgium, Canada, France, Japan and Sweden, income support is focused on large families. In most Anglo-Saxon and Southern European OECD countries where poverty rates are higher, cash benefits are means-tested and directed towards low-income families.15

Spending on child-related tax breaks is generally lower than cash benefits.16 Nonetheless, child-related tax benefits are widespread across the OECD: only six countries do not grant specific tax deductions to families.17 In the United States, tax breaks are the main levy to support families. Tax breaks granted to families in addition to cash benefits are also important source of transfers in France, Belgium and Germany.18 Likewise, parents in Singapore enjoy tax rebates in the form of Parenthood Tax Rebate (PTR), Working Mother’s Child Relief (WMCR), Qualifying Child Relief (QCR) and the Grandparent Caregiver Relief (GCR).19

Childcare Services

Coverage of childcare services for children under 3 years old is also a key determinant of fertility re-increases, particularly in OECD countries with high levels of female employment. Access to childcare services help parents better combine caregiving responsibilities with gainful employment. The indirect cost of having children is thus reduced. This is especially relevant to women who actively participate in the labour market, since women are still predominantly saddled with caregiving responsibilities. In most OECD countries, investments in early childhood education and care (ECEC) services have increased over the past decade.20 The OECD-average formal childcare participation rate (under 3 years old) has increased accordingly, from 29% to 34% between 2006 and 2014.21

It should be noted that data from the OECD captures the use of formal childcare services, which generally include centre-based services (e.g., nurseries or day-care centres and pre-schools, both public and private), organised family day care, and paid professional care services. It excludes data on the use of unpaid childcare services provided by relatives and the corresponding effect on TFR—important considerations in the context of Singapore, where the family remains positioned as the primary unit of care. Evidence from the OECD seems to suggest that Singapore’s move towards increasing access to formal childcare services is a step in the right direction, but some parents may still prefer family-centred and home-based care options, which should be taken into consideration. While enrolment rates in centre-based care may be high and increasing, this could be the result of a lack of viable alternatives or preferred caregiving solutions for parents.

Leave Entitlements

Evidence suggests that the duration of paid and employment-protected maternity and paternity leave are positively associated with TFR, although the latter effect is less statistically significant.22 There are large variations in leave entitlements across the OECD, due to cross-national differences in norms surrounding the roles of mothers and fathers in raising kids and employer attitudes towards child-related leave, among other reasons. On average, mothers in OECD countries are entitled to 18 weeks of paid maternity leave around childbirth; the US is the only OECD country that offers no statutory entitlement to paid leave on a national basis.23 While maternity leave is generally reserved for mothers, some countries such as Poland and the UK have allowed a part of it to be transferred to fathers—similar to Singapore’s Shared Parental Leave scheme, where working fathers can share up to 4 weeks of the 16-week maternity leave.

To foster more equal sharing of caregiving responsibilities, paid leave entitlements for fathers have increased over the years. Some OECD countries have even introduced “quotas”, “bonus months” or a “gender equality bonus” to encourage greater use of paternity leave, though in many places, fathers continue to use less than what they are entitled to.24 There is reason to encourage fathers’ use of parental leave: evidence from the Nordic countries revealed that couples are more inclined to have a second child if fathers take parental leave with the first child.25 However, paid leave entitlements for fathers remain shorter than what is provided to mothers. On average, OECD countries offer just over 8 weeks of paid father-specific leave. In one-third of OECD countries, fathers enjoy 10 weeks or more of paid leave, with fathers enjoying as long as 12 months of paid leave in Japan and South Korea. At the other end of the scale, eight OECD countries provide no paid father-specific leave, and 13 offer two weeks or less.26 Singapore, which saw the recent extension of two-week government-paid paternity leave to working fathers, falls closer to the latter spectrum.27

Normative Considerations

There is no one-size-fits-all policy approach, but evidence suggests that the key to raising TFR is to provide parents, especially mothers, with more opportunities to combine work and family life. Policies play a significant role in increasing these opportunities, but they alone do not guarantee a fertility rebound, just as how South Korea and Japan continue to face low TFR (1.17 and 1.44 respectively in 2016)28 despite significant reforms to their family policies. In the two countries, the effectiveness of most well-meaning policies are mitigated by unfavourable workplace cultures, such as expectations to work overtime and where the use of parental leave is frowned upon by colleagues. Evidently, policies must be considered within the context of a wider system of cultural and structural factors, where the labour market context, gender and marriage norms also influence parenthood decisions and fertility trends.

The effectiveness of most well-meaning policies are mitigated by unfavourable workplace cultures; evidently, policies must be considered within the context of a wider system of cultural and structural factors.

Creating a family-friendly workplace culture

The likelihood of a fertility rebound is also contingent on a more family-friendly workplace culture in society—one which supports work-life reconciliation. All members of society have a part to play in creating such a culture, and the government can facilitate this in several ways.

For one, more can be done to encourage and normalise flexible working arrangements (FWAs). In Singapore, access to FWAs remains largely dependent on private negotiations between employers and employees. To strengthen employees’ bargaining power over the use of FWAs and guarantee employer provision of workplace flexibility, some OECD countries introduced legislations surrounding FWAs: in the UK and the Netherlands, all employees have the legal right to request flexible working—not just parents and caregivers.29 Inevitably, there will be concerns surrounding the implementation of workplace flexibility. Platforms for dialogue among different stakeholders can help to address these. In Germany, for instance, over 1,200 companies are connected in a state-coordinated platform which facilitates the exchange of best practices on ways to develop workplace flexibility and family-friendly workplaces. Firms can also be nudged to internalise the responsibility of implementing family-friendly workplace practices. One way is to leverage a system of public audits, where firms are required to report on their efforts at implementing such practices. This provides firms with the flexibility to tailor and administer family-friendly workplace practices according to their business needs, while still holding them accountable to their employees and society at large.

The likelihood of a fertility rebound is also contingent on a more family-friendly workplace culture in society.

Better gender equity at home

Fertility trends are also influenced by the gender division of labour at home—a sphere that remains largely beyond the reach of policies. Studies have shown that more gender-egalitarian basis are more likely to have second children.30

Nevertheless, the type of unpaid work each partner does, and how long each spends on it, have different effects on the likelihood of having more children. For example, in Finland, greater male contribution to childcare work boosts TFR but their contribution to housework does not. These findings provide reason for Singapore to work harder towards better gender equity at home. Married working women generally contribute more to caregiving and household chores compared to married working men.31 Notwithstanding the gender gap in the domestic sphere, a study found that some women (and men) still reported good work-life balance, although they were more likely to have someone in the family to take care of domestic matters, be it grandparents or foreign domestic workers.32 This suggests that the dual role of women in the paid labour market and unpaid domestic sphere can co-exist and is manageable as long as the conflict is contained. This may call for personalised, private solutions to work-family contradictions, and perhaps trade-offs in the number of children parents decide to have.

Studies have shown that more gender egalitarian behaviour and sharing of unpaid household work can lead to increases in birth rates.

Changing norms and aspirations surrounding marriage and parenthood

In some OECD countries, re-increases in TFR were observed together with greater acceptance of out-of-wedlock births, a trend that has increased in almost all OECD countries.33 In 1964, most OECD countries had no more than 10% of births outside of marriage.34 Today, only five OECD countries (Greece, Israel, Japan, South Korea and Turkey) have proportions of births out of wedlock that remain below 10%.35 In Belgium, Denmark, France, Norway and Sweden, over 50% of births occur outside of marriage. In these countries, government assistance is typically provided to unwed parents as well.

In Singapore, however, family benefits are not equally extended to unwed parents as parenthood within marriage remains the prevailing norm.36 Although certain family benefits were extended to unwed single mothers recently, the Singapore Government stressed that the move was not to undermine the prevailing social norm of parenthood within marriage, but to recognise the difficulty that unwed parents face in raising children single-handedly, and to support their efforts to provide for their children as well as their children’s developmental or caregiving needs.37 As unwed parenthood continues to be framed within a paradigm of vulnerability and exception today, there may come a time for Singapore to re-examine whether marriage is a necessary precondition to parenthood, as well as to receiving parenthood benefits provided by the state. Norms surrounding marriage and parenthood are not fixed, as the OECD trend clearly indicates.

While parenthood norms may remain conservative in Singapore, aspirations surrounding marriage are changing: The National Youth Survey in 2016 found that 31% of over 3,500 Singaporean youth respondents believe that it is not necessary to marry. This figure rose from 17% in 2010, despite government measures encouraging marriage.38 Where procreation predominantly occurs within marriage, the normalisation of singlehood and corresponding decline in marriage rates have real implications on Singapore’s TFR.

Social dialogues can, however, address changing norms and aspirations surrounding marriage and parenthood perhaps beyond the limits of government policy. On one hand, by hearing from parents’ perspectives, singles can be better sensitised to the intrinsic and largely invisible rewards of getting married and having children. On the other hand, singles can articulate the inertia and constraints they face when making decisions on marriage and parenthood. These conversations may spark innovative solutions targeted at specific concerns of different strata of society. They may even help the government find the right narrative and messaging to encourage marriage and parenthood, towards the goal of raising Singapore’s TFR.

Social dialogues can, however, address changing norms and aspirations surrounding marriage and parenthood.

Conclusion

Singapore’s demographic shape is changing rapidly, but raising fertility rates is a complex task with no quick fix or instant panacea. In addition to policy instruments that promote better work-life reconciliation, normative dimensions such as workplace culture and practices, gender roles in the paid and unpaid labour market, and norms surrounding marriage and parenthood are also key factors to consider. To achieve a fertility rebound, Singapore has to build a holistic ecosystem that accounts for all these factors.

NOTES

- Strategy Group, “Citizen Population Scenarios”, April 1, 2012, accessed August 23, 2018, https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/media-centre/press-releases/article/details/citizen-population-scenarios.

- Data.gov.sg, “Births and Fertility, Annual”, accessed August 23, 2018, https://data.gov.sg/dataset/births-and-fertility-annual?view_id=f90ee2cb-d4cb-4386-b90f-ed86f52730f6&resource_id=f63d5535-f094-42d0-b7ff-dbcbccb97928.

- Strategy Group, “Population in Brief 2017”, September, 2017, accessed August 23, 2018, https://www.strategygroup.gov.sg/docs/default-source/default-document-library/population-in-brief-2017.pdf.

- Raising TFR is but one of the strategies to address Singapore’s population challenge, but it is not within the scope of this article to explore all the different means.

- Kanwaljit Soin, “Assess the Impact of Big Baby Budget”, The Straits Times, April 8, 2016, accessed August 21, 2018 , www.straitstimes.com/opinion/assess-the-impact-of-big-baby-budget; National Population and Talent Division, Background on Population and Marriage and Parenthood Trends and Policies in Singapore (Singapore: NPTD, 2017).

- Soin, “Assess the Impact of Big Baby Budget”; Department of Statistics, “Births and Fertility, Annual” , accessed August 23, 2018, https://data.gov.sg/dataset/births-and-fertility-annual?view_id=f90ee2cb-d4cb-4386-b90f-ed86f52730f6&resource_id=f63d5535-f094-42d0-b7ff-dbcbccb97928.

- Angela Luci and Olivier Thevenon, “Does Economic Development Drive the Fertility Rebound in OECD Countries?”, Working Paper, No. 167, 2010, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/19557/dt_167.fr.pdf.

- Angela Luci and Olivier Thevenon, “Does Economic Development Explain the Fertility Rebound in OECD Countries?”, Population & Societies 481 (September 2011).

- Angela Luci and Olivier Thevenon, “The Impact of Family Policy Packages on Fertility Trends in Developed Countries”, European Journal of Population 29, no. 4 (November 2013).

- Pearl Lee, “Long Hours Common for Some Professions in Singapore”, The Straits Times, January 17, 2017, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/long-hours-common-for-some-professions-in-singapore.

- OECD, “PF1.1: Public Spending on Family Benefits”, 2017, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF1_1_Public_spending_on_family_benefits.pdf.

- Willem Adema, Nabil Ali, and Olivier Thevenon, “Changes in Family Policies and Outcomes: Is there Convergence?”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 157, 2014, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/docserver/5jz13wllxgzt-en.pdf?expires=1534841634&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=F2BDA6389D2A243F73F050B79DE0EAF6.

- OECD, “PF1.1: Public Spending on Family Benefits”.

- The 9 countries are: France, Germany, Japan, South Korea, Mexico, the Netherlands, Slovenia, Spain and the US. See Willem Adema, Nabil Ali ,and Olivier Thevenon, “Changes in Family Policies and Outcomes: Is there Convergence?”.

- Olivier Thevenon, “Family Policies in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis”, Population and Development Review 37, no. 1 (March 2011): 57–87.

- Some countries give out tax benefits universally, even to people who do not pay taxes. This is unlike Singapore, where tax benefits are only given to those who pay taxes. That said, the relationship between universal tax benefits and TFR is unclear.

- Tax breaks are not used in Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Italy, Luxembourg or Sweden. See Angela Luci and Olivier Thevenon, “The Impact of Family Policy Packages on Fertility Trends in Developed Countries”.

- Public spending on tax breaks accounts for over 2% of GDP in these countries. See Olivier Thevenon, “Family Policies in OECD Countries: A Comparative Analysis”.

- Unwed parents are eligible for the PTR so long as their marriage is registered before their child reaches 6 years old. Only working mothers who are married, divorced or widowed are eligible for the WMCR and GCR.

- These include spending on subsidies to childcare service providers, earmarked payments to parents, and home-help childcare services for families in need. See Willem Adema, Nabil Ali, and Olivier Thevenon, “Changes in Family Policies and Outcomes: Is there Convergence?”

- OECD, “PF3.2: Enrolment in Childcare and Pre-School”, 2016, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF3_2_Enrolment_childcare_preschool.pdf.

- Willem Adema, Nabil Ali, and Olivier Thevenon, “Changes in Family Policies and Outcomes: Is there Convergence?”

- OECD, “PF2.1: Key Characteristics of Parental Leave Systems”, 2017, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/els/soc/PF2_1_Parental_leave_systems.pdf.

- Willem Adema, Nabil Ali, and Olivier Thevenon, “Changes in Family Policies and Outcomes: Is there Convergence?”

- Contrary to the results for the first child, fathers’ uptake of parental leave with the second child does not increase, but lowers the couple’s inclination to have a third child.

- OECD, “PF2.1: Key Characteristics of Parental Leave Systems”.

- Additionally, working parents of Singapore citizen children under 7 years old are each entitled to 6 days of paid childcare leave per year.

- KOSIS, “Vital Statistics of Korea”, accessed August 21, 2018, https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1B8000F&conn_path=I2&language=en; Statistics Japan, “Statistical Handbook of Japan 2017”, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.stat.go.jp/english/data/handbook/pdf/2017all.pdf.

- As provided under the Dutch Flexible Working Hours Act and UK’s Flexible Working Act. Granting all employees with the right to request for flexible working arrangements (FWAs) can reduce the risk of discrimination against certain groups of employees, as for instance parents, when they are the only or predominant group claiming for FWAs.

- Olivier Thevenon, “Policy Approaches and Strategies to Raise TFR: International Experience and Lessons for Singapore” (presentation for New Insight Series: Perspectives on Family and Fertility Policies, Civil Service College, Singapore, March 29, 2017).

- Compared to married working men, the proportion of married working women who were equally or primarily responsible for caregiving and household chores were 43 and 38 percentage points higher respectively. See Ministry of Social and Family Development, “Family and Work”, Insight Series, paper no. 4, 2017.

- Over 90% of women surveyed reported that they were happy with the division of domestic labour. As reported in Paulin Straughan and Mathew Mathews, “Singapore’s Population Challenges” (presentation for New Insight Series: Perspectives on Family and Fertility Policies, Civil Service College, Singapore, March 29, 2017).

- Angela Luci and Olivier Thevenon, “ The Impact of Family Policy Packages on Fertility Trends in Developed Countries”.

- OECD, “SF2.4: Share of Births Outside of Marriage”, 2016, accessed August 21, 2018, https://www.oecd.org/els/family/SF_2_4_Share_births_outside_marriage.pdf.

- The proportion of out-of-marriage childbirths in Singapore has remained low over the years—an indication that having children outside of marriage is not the norm.

- Singapore Parliamentary Debates, Committee of Supply—Head I (Ministry of Social and Family Development), Vol. 94, Sitting No. 17 (April 12, 2016).

- Yuen Sin, “Young People’s Attitudes towards Other Races and Nationalities Have Improved: Survey”, The Straits Times, July 14, 2017, accessed August 21, 2018, www.straitstimes.com/singapore/young-peoples-attitudes-towards-other-races-and-nationalities-have-improved-survey.