Could Crowdfunding Work for Singapore’s Public Sector?

ETHOS Digital Issue 02, Apr 2018

Like many developed countries, Singapore faces an increasingly challenging economic and political environment, with a tightening fiscal position,1 as well as rising public expectations for more citizen involvement in shaping and implementing public policy. While Public Private Partnership (PPP) models have been used to bring innovation, cost-sharing and collaboration to the development of some national assets, they are relatively large-scale and less amenable to unexpected changes such as shifts in public demand.2 In a rapidly changing administrative environment, we should explore other funding models that could provide flexible financing options for public sector projects.

One such alternative is crowdfunding. This refers to collective efforts by individuals who pool their money together, usually via online platforms, to invest in or support projects initiated by a given person, group, organisation or business. Regular donation is but one of many crowdfunding models. Donation-based and reward-based crowdfunding have become innovative methods for entrepreneurs to raise capital for their projects. Online crowdfunding—through platforms such as Kickstarter3, Indiegogo4 or Give.Asia5—have been very successful in generating revenue for some projects, sometimes on a global scale.

Other funding models could provide flexible financing options for public sector projects; one such alternative is crowdfunding.

Civic Crowdfunding

In some countries civic crowdfunding has attracted attention for its ability to garner citizen funds towards specific public projects. Civic crowdfunding refers to the direct funding of public, civic or community projects by citizens, in collaboration with the government. It allows projects to potentially attract a much broader base of resource provision and support than may be available through public funding. It also helps free up limited public resources for other more pressing needs best served directly by the government.

Crowdfunding platforms generally allocate raised funds in two main ways: through an “All-Or-Nothing” (AoN) model or a “Keep-It-All” (KIA) model.6 The main difference is what happens to funds raised if a stated funding goal is not achieved within a specified period of time. With the AoN model, funds are returned to the contributor if the funding target is not met, and the project creator does not receive any funds. This means that if a project does not manage to garner sufficient support from the public, it will not proceed, and contributors will incur no cost.

The KIA model allows the project creator to keep any amount of money raised even if the funding target is not met and the project is not fully funded. Civic crowdfunding platforms available in the United Kingdom and United States such as Spacehive and Citizinvestor operate on an AoN model, which is said to raise more money due to the sense of urgency it creates.

Pros and Cons of Crowdfunding

While civic crowdfunding has both pros and cons (see Figure 1), the concerns most often raised can be refuted on several grounds.

Figure 1. Arguments For and Against Civic Crowdfunding7

Firstly, the crowding out effect (resulting from competition between government and charities for private sector donations using crowdfunding) may not be substantial. This is especially true if a government seeks crowdfunding for projects that do not involve large sums of money, or there are significant number of people contributing to the project, resulting in low contribution per capita.

Next, the relegation of public issues to people’s passing (i.e., citizens can veto public projects which are supposedly government responsibility) only applies, if the “All-Or-Nothing” fund collection model is adopted. This vulnerability could be mitigated if the government were to co-fund part of the cost, to ensure the project can at least take off, while encouraging the public to contribute the rest.

Thirdly, far from “distracting” the government from its mission, crowdfunding could free up the public sector to shift to a more facilitative or regulatory role. Government could focus on significant infrastructure that the state can best provide (e.g., defence), or intervene in critical market failures, while allowing crowdfunding to serve as a form of market self-regulation and public decision-making, in which the public chooses the services or facilities they prefer to support. This could in fact free the public sector from the burden of assessing trade-offs for projects in which a local community may be in a better position to make its own decisions (e.g., community-based amenities or cultural activities).

Finally, detractors might argue that crowdfunding may lead to a slippery slope of turning individual altruism into collective public responsibility. They suggest that crowdfunding may blur the lines between government responsibility and individuals’ willingness to contribute to the greater good. Donations may gradually become mandatory for everyone in order to reap the benefits of projects. This can be avoided so long as government does not abuse the use of this financing tool in the long run, and by being transparent in budgeting for actual needs.

Civic Crowdfunding in the Singapore Public Sector: Is it Feasible?

Figure 2. Types of Collaborative and Crowd-Based Project Models in Singapore’s Public Sector

Crowdfunding, which has become a tried and tested model in the private sector, is not new to Singaporeans. However, it is still a novel approach to funding projects in the public sector here. Nevertheless, such funding mechanisms have been tried and tested for projects to do with the public good, in countries such as the United Kingdom and United States (see box stories below).

Spacehive is the United Kingdom’s civic crowdfunding platform.

United Kingdom

Spacehive1 is the United Kingdom’s civic crowdfunding platform. A winner of the Prime Minister’s Big Society Award, Spacehive helps local communities propose and crowdfund neighbourhood improvement projects.2 The aim is to gather ideas and funding widely in order to spur grassroots transformation. Unlike other crowdfunding platforms, the unique feature of Spacehive is that projects are mainly about transforming communities, spaces and places.

Featuring an All-Or-Nothing funding model, over £1 million worth of projects have been funded to date, with 52% of the projects initiated achieving their funding targets successfully.3 This is significantly higher than other platforms such as Kickstarter which only enjoy a 31% success rate. This may be due to strong local support for community projects on Spacehive. To ensure feasibility, every Spacehive project is verified by independent partner organisations before funding commences. One such organisation is the Association of Town and City Management (ATCM), which encompasses both public and private sector stakeholders.4

Notes

- Association of Town and City Management (website), accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.atcm.org/.

- GOV.UK, "Prime Minister Hails the Rise of 'Civic Crowdfunding'", November 27, 2014, accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-hails-the-rise-of-civic-crowdfunding.

- Aaron O’Dowling-Keane, “Which Platform Has the Highest Success Rate?”, Spacehive, January 19, 2017, accessed June 7, 2017, https://about.spacehive.com/which-crowdfunding-platform-has-the-highest-success-rate/.

- Spacehive (website), accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.spacehive.com/.

In the United States, citizens are encouraged to contribute to crowdfunding for local government projects on Citizinvestor, a civic engagement platform.

United States

In the United States, citizens are encouraged to contribute to crowdfunding for local government projects on Citizinvestor,1 a civic engagement platform. Unlike the United Kingdom’s Spacehive, US government entities and their official partners will post projects on Citizinvestor that already have support from the local municipal government and the public, but which have not been implemented due to budget issues. The platform also features public projects that citizens propose, as well as those that would normally not be funded by the local government.

Citizinvestor features two business models for its crowdfunding system. The first allows government partners to freely post projects on the site, with Citizinvestor charging an 8% service fee for each successful project. It operates on an All-Or-Nothing model. Citizinvestor monitors the entire project timeline from funding to completion, and an app promotes projects to interested citizens. The second features an annual subscription fee for using Citizinvestor Connect—a software platform where government partners can set up their own customised sites to host projects. Citizinvestor Connect also enables citizens to propose ideas that can be turned into crowdfunded projects.

The success rate for projects reaching their funding goals is hugely impressive, reaching some 60%.2 While the sums raised for public goods such as parks and other urban amenities are relatively small, Citizinvestor has nevertheless been successful in meeting its funding goals. This has been attributed to the high levels of civic engagement that residents of US cities tend to desire.3

Notes

- Sarah Rich, “Citizinvestor: The New Frontier of Government Funding?”, Government Technology, October 25, 2012, accessed June 7, 2017, http://www.govtech.com/budget-finance/Citizinvestor-New-Frontier-Government-Funding.html.

- Jason Shueh, “Startup Helps Cities Launch Crowdfunding Campaigns”, Government Technology, February 11, 2016, accessed 7 June, 2017, http://www.govtech.com/products/Startup-Helps-Cities-Launch-Crowdfunding-Campaigns.html.

- "Jordan Raynor of Citizinvestor on Creating a Civic Crowdfunding Platform", The Guardian video clip posted December 6, 2013, accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/media-network/media-network-blog/video/2013/dec/06/jordan-raynor-citizinvestor-civic-crowdfunding.

Crowdfunding, a tried and tested model in the private sector, is still a novel approach to funding projects in the public sector.

Making Civic Crowdfunding Work

For civic crowdfunding to be a viable option in Singapore’s public sector, some considerations should be taken into account.

The first involves the current philanthropy landscape in Singapore. According to the World Giving Index, Singapore was ranked 19th for donating money to charity, compared the United Kingdom (7th) and United States (13th).8 Nevertheless, charitable giving in Singapore appears to be on the rise, reaching a 17-year high in 2016 of $1.4 billion in tax-deductible donations.9 If this rising trend continues, there is a reason to be optimistic that Singaporeans will become more willing to contribute to public causes through crowdfunding.

One likely conundrum in Singapore, however, is that there may be no strong conviction that citizen contributions are needed for public goods. Unlike countries such as the United Kingdom, which has adopted austerity limits on public expenditure, there is strong public perception that Singapore enjoys sufficient reserves, and a healthy fiscal position. In other words, Singaporeans may be reluctant to participate in civic crowdfunding if they believe that the government could afford to allocate more resources if it so chose, without having to resort to public contributions. Nevertheless, crowdfunding can have benefits beyond relieving a government’s fiscal woes: it can enable more nimble and flexible interventions on the ground, and also engender a sense of a shared stake in a nation’s wellbeing and greater shared ownership of local issues.

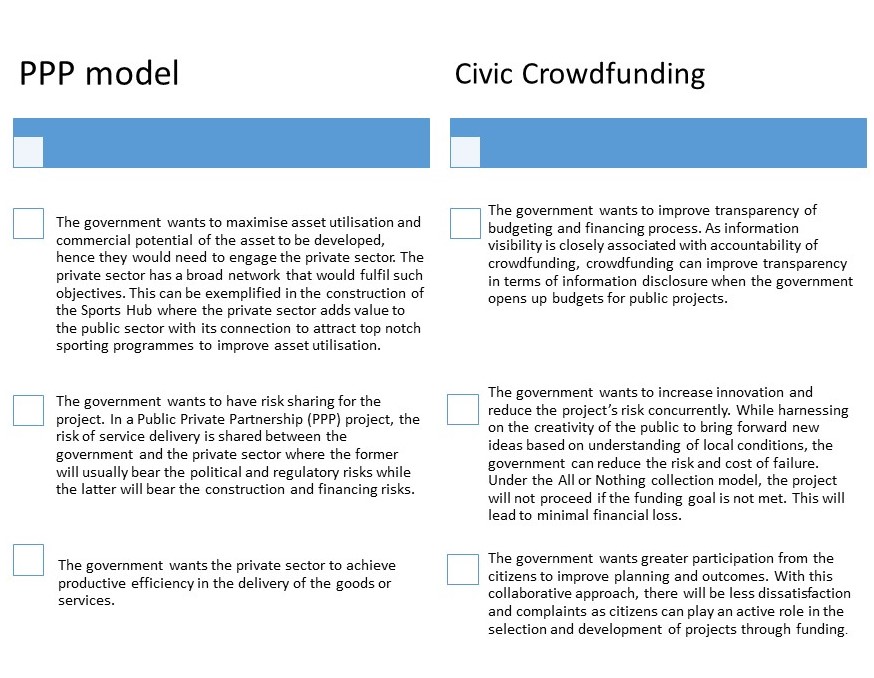

Another consideration is that crowdfunding is not meant to replace Public-Private Partnerships (PPP). The expertise and investment of the private sector will still be needed to drive innovation and attain cost efficiency at scale. A range of factors can help determine whether a project might be better served through PPP approaches, or civic crowdfunding:

Figure 3. Different Objectives, Different Approaches10

The final consideration is accountability. The government will need to be comfortable with accounting for crowdfunded projects. Besides financial management, the public sector will have to determine its short- or long-term responsibility for such projects, including over their performance or any externalities that may arise. The public sector may also need to address concerns that the government could become over reliant on crowdfunding in the long run, in lieu of setting aside adequate budgetary provisions for such public goods or services.11 There is a risk that public agencies may potentially defer important investments if crowdfunding goals are not met. Judicious selection of the appropriate crowdfunding mechanism (i.e., either All-Or-Nothing or Keep-It-All) will be vital, as well as clarity about whether the project ought to proceed even if it fails to meet its crowdfunding targets. This may involve specifying different funding threshold levels, for instance.

What drives civic crowdfunding?

Opportunities and Challenges in Civic Crowdfunding Projects

Source: See page 14 of Alexandra Stiver, Leonor Barroca, Shailey Minocha, Mike Richards and Dave Roberts, “Civic Crowdfunding Research: Challenges, Opportunities, and Future Agenda”, New Media & Society, 2014: 1–23, accessed June 7, 2017, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/fd27/8ab7e86badb66761484495ea2e525946a723.pdf.

In implementing crowdfunding, the government should also consider whether public motivation and impulsive altruism are dependable or sustainable over a longer time frame.

Conclusion

Civic crowdfunding presents a feasible alternative to expanding Singapore’s range of public sector financing options. While changing citizen mindsets towards philanthropy and crowdfunding could be challenging, small trials could be carried out to test the potential of civic crowdfunding for appropriate public projects. In implementing crowdfunding, the government should also consider whether public motivation and impulsive altruism are dependable or sustainable over a longer time frame,12 as politically sensitive issues of accountability and transparency may surface. To mitigate this issue, effective public communications and engagement strategies need to be formulated as well, so that citizens understand the value and purpose of such approaches in creating broader public value, and contributing to social resilience.

NOTES

- Public expenditure is expected to outweigh revenue in the long term. The Singapore Government has also recently lowered budget caps permanently across all ministries by 2%. See: Rachel Au-Yong, “Singapore Budget 2017: Budgets to Grow at A Slower Pace, Future Tax Raises Being Considered”, The Straits Times, February 20, 2017, accessed June 7, 2017, http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/singapore-budget-2017-budgets-to-grow-at-a-slower-pace-future-tax-raises-being-considered; Ann Williams, “2016 Singapore Budget Will Have Surplus of $3.45 Billion”, The Straits Times, March 24, 2016, accessed June 7, 2017, http://www.straitstimes.com/business/economy/2016-budget-will-have-surplus-of-345-billion.

- Kickstarter (website), accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.kickstarter.com/about?ref=nav.

- Indiegogo (website), accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.indiegogo.com/about/what-we-do.

- See Fintechnews Singapore, “Top 11 Donation and Reward-Based Crowdfunding Platforms in Asia”, June 24, 2017, accessed June 7, 2017, http://fintechnews.sg/10112/crowdfunding/top-donation-reward-based-crowdfunding-platforms-asia/.

- Sigeru Omatu, Qutaibah M. Malluhi, Sara Rodriguez Gonzalez, Grzegorz Bocewicz, Edgardo Bucciarelli, Gianfranco Giulioni, and Farkhund Iqba, ed., Distributed Computing and Artificial Intelligence, 12th International Conference, (Switzerland: Springer, 2015), 114–115.

- Sources: Mark Rosenman, “Why 'Crowdfunding' Government Is a Bad Idea”, Philanthropy News Digest, March 11, 2015, accessed July 7, 2017, https://philanthropynewsdigest.org/commentary-and-opinion/why-crowdfunding-government-is-a-bad-idea; Future Cities Catapult, Civic Crowdfunding: A Guidebook for Local Authorities, accessed June 7, 2017, http://futurecities.catapult.org.uk/resource/civic-crowdfunding-guidebook-local-authorities/; Chang Heon Lee, J. Leon Zhao and Ghazwan Hassna, “Government-Incentized Crowdfunding for One-Belt, One-Road Enterprises: Design and Research Issues”, Financial Innovation 2, no. 2 (2016): 4–7, accessed June 7, 2017, https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1186%2Fs40854-016-0022-0.pdf.

- Charities Aid Foundation, CAF World Giving Index, October 2016, accessed June 7, 2017, http://www.cafamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/1950A_WGI_2016_REPORT_WEB_241016-1.pdf.

- Ng Huiwen, “S'pore Ranks 28th in World Giving Index”, The Straits Times, October 27, 2016, accessed June 7, 2017, http://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/spore-ranks-28th-in-world-giving-index.

- Sources: Ministry of Finance, Public Private Partnership Handbook (Version 2, March 2012), pages 6–8, accessed June 7, 2017, http://www.mof.gov.sg/Portals/0/Policies/ProcurementProcess/PPPHandbook2012.pdf; Future Cities Catapult, Civic Crowdfunding: A Guidebook for Local Authorities, pages 19–20, accessed June 7, 2017

- Bernholz.L, Reich. R, Emma.S, Crowdfunding for Public Goods and Philanthropy”, Digital Civil Society, July 16, 2015, accessed

June 7, 2017, https://medium.com/the-digital-civil-society-lab/crowdfunding-for-public-goods-and-philanthropy-c7c7c5976898. - Mark Rosenman, “Why 'Crowdfunding' Government Is a Bad Idea”, Philanthropy News Digest, March 11, 2015, accessed June 7, 2017, http://philanthropynewsdigest.org/commentary-and-opinion/why-crowdfunding-government-is-a-bad-idea. Also see Mark Roseman, “We Can’t Crowdfund Government Programs”, The Chronicle of Philanthropy, February 26, 2015, accessed June 7, 2017, https://www.philanthropy.com/article/Opinion-We-Can-t-Crowdfund/227875.